Column: 130 years ago, a Los Angeles tamale vendor was robbed. How times haven’t changed

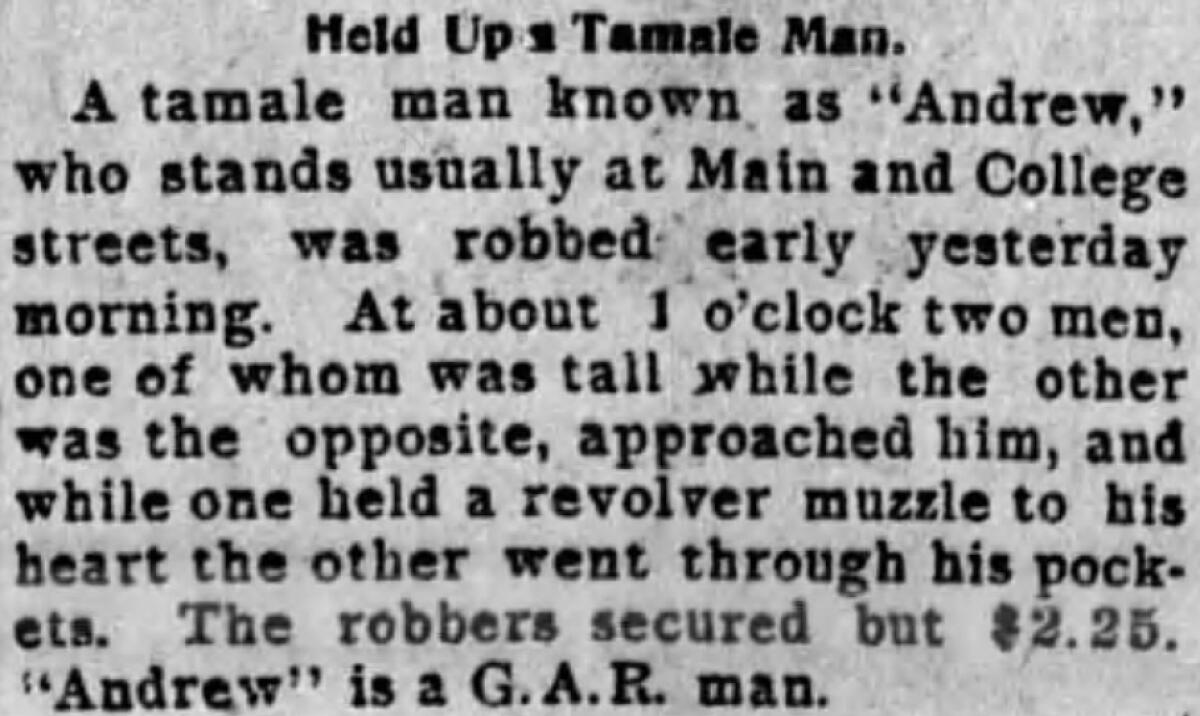

Andrew the tamale man didn’t stand a chance.

He was at his usual spot, near Main and College streets, at 1 a.m. when two men approached. One pressed a gun to his chest; the other picked through his pockets. They made off with his earnings for the night: $2.25.

The robbery was part of a crime wave against street food vendors in Los Angeles, breathlessly reported on by the media. Police and prosecutors announced they would go after scofflaws like Andrew’s assailants. Vendors set up security details. Meanwhile, politicians continued a push to outlaw tamaleros and their ilk, claiming they didn’t follow health regulations and weren’t registered to do business in the city.

Sounds familiar, right? Except this paper reported on Andrew the tamale man’s bad fortune 130 years ago.

Nearly a decade later, in 1901, another Times dispatch marveled at L.A.’s street food scene:

“Strangers coming to Los Angeles remark at the presence of so many outdoor restaurants, and marvel at the system which permits men … to set up places of business in the public streets … competing with businessmen who pay high rents for rooms in which to serve the public with food.”

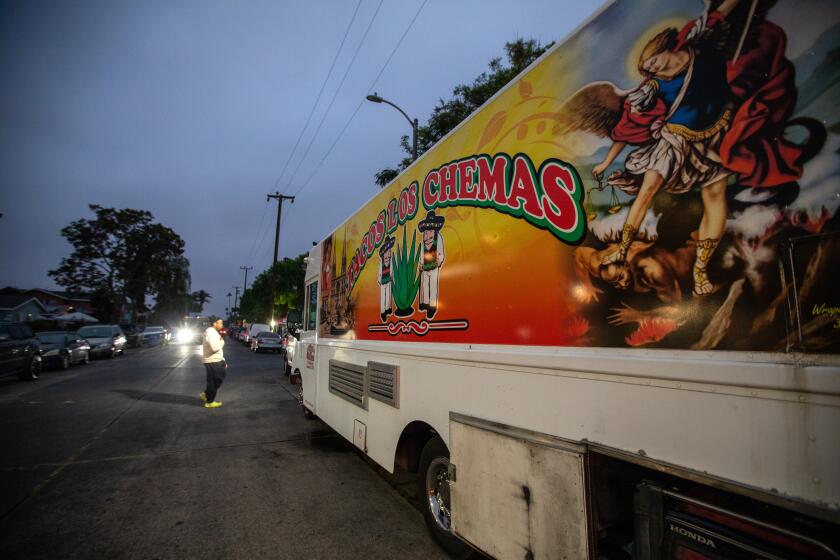

Since the start of the pandemic, but especially since the California Legislature passed laws last year that decriminalized the selling and production of street food, the trade has exploded. Taco trucks have turned into taco tents that take up sidewalks and driveways. Diners sit on sidewalks and feast on dishes as simple as gelatin in plastic cups and as complex as goat barbacoa baked for hours in a backyard pit. I’ve seen stands with the same handwritten signs advertising “coco frio” (cold coconut), along with the same rainbow-colored umbrellas, from the Coachella Valley to a dirt turnout off Malibu Canyon Road in the Santa Monica Mountains.

City governments from Santa Ana to Santa Monica to San Diego and even Los Angeles have tripped over themselves to severely limit where taco men, fruit ladies, pupusa makers, hotdogueros and others can operate, and to seize the equipment of sellers with no permits. Irate individuals have overturned carts and spat on grills, going viral on social media.

At the same time, criminals have increasingly targeted the vendors to the point that Los Angeles Police Department Deputy Chief Kris Pitcher described a recent spate of taco truck stickups to my colleagues Daniel Miller, Ruben Vives and Richard Winton as an “emerging crime trend.” The most brazen instance was on Aug. 16, when the same robbers targeted six street vendors across Echo Park, Hollywood and downtown L.A. in the span of two hours.

A rash of robberies targeting food trucks and stands across L.A. — including six in mid-August — has had a chilling effect on the industry.

I’ve compiled dozens of newspaper clippings on street food vendors in Los Angeles from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when Americans were discovering Mexican cuisine and L.A. was already one of the best cities to find it. I retold some of those long-ago anecdotes in my 2012 book, “Taco USA: How Mexican Food Conquered America,” which maintained that there’s really nothing new under the Mexican food sun in this country — that everything is cyclical, based on templates as set in place as the cheese on a cold quesadilla.

Disputing the pros and cons of street food is a longer tradition in Los Angeles than Hollywood, jacarandas and USC football — but far more annoying than all of them combined. The only thing that changes is the food offered, the technology to cook it and how it’s promoted. The pitched battles happening right now, that fans and foes alike describe as unprecedented … aren’t.

That’s why I scroll past the umpteenth TikTok video of chicharrones fried in the back of someone’s pickup truck. Why I rolled my eyes earlier this year when Orange councilmember Kathy Tavoularis blasted unlicensed food vendors in her city as “not entrepreneurial,” “gang-like” and “another attempt to get into our neighborhoods,” claiming they “cheated” restaurant owners “out of business.” Why I scoffed when Anaheim spokesperson Mike Lyster told The Times last year that anyone who buys street tacos or tamales “could be unknowingly contributing to human trafficking and exploitation” but didn’t offer proof of either.

The Gilded Age called, Kathy and Mike: They want their blowhard bureaucrats back.

Even the complaints from brick-and-mortar restaurant owners that it’s unfair for street vendors to operate without paying rent, utilities and taxes are as soggy as a wet burrito. Only one thing governs street food: the free market. And believe me, it’s more ruthless than any code enforcement officer could ever dream to be.

L.A.’s tamale men of yore largely disappeared when restaurants — once almost exclusively a hoity-toity affair — became affordable, and Angelenos moved on to other Cal-Mex dishes like tacos and chile verde. Lunch trucks slinging sandwiches took their place in the 1950s, followed by taco trucks in the 1970s to today’s free for all. All along, stalls have lived and die by the quality of their food.

A few months ago, a fruit vendor with one of those rainbow-colored umbrellas hawked his stuff in front of a random house in my middle-class, mostly Latino Orange County neighborhood. There were whispers of there-goes-the-barrio, but I told folks that the vendor wouldn’t last: his fruit was forgettable. Sure enough, the frutero was gone within weeks and never returned.

On the other hand, a family has set up a table on a nearby residential street for years. All they do is sell aguas frescas: horchata, pineapple, mashed strawberries in chilled evaporated and condensed milk. The flavors are crisp and refreshing, with chunks of fruit bobbing in each glass jug. On a hot summer day, I buy something from them at least once a month and have seen cops chug down their purple-toned prickly pear drink with glee.

Let food vendors sell where they may. Get the government out of the way. Support people hustling to make a living.

Old-fashioned capitalism is why municipalities need to give up their war against street food. It’s a waste of taxpayer money as well as the time of public employees who have better things to do than toss freshly grilled corn-on-the-cob into a garbage bag. Spend all those resources on the one problem that has never been solved: vendors remaining as vulnerable to crime as Andrew the tamale man.

In turn-of-the-century Los Angeles, they were white, Black and Mexican men. Today, they’re mostly Mexican and Central American men, women and teenagers. They have always been the working poor, scraping by in jobs that are the envy of no one. Aren’t those the hustlers that cities should want to protect and uplift?

I’m not going to pretend that all street vendors are faultless. Law enforcement should enforce statutes against littering, wage theft, extortion and other behaviors that actually harm communities. Selling food on the street is not that.

One of my other archival clippings is from the March 25, 1894, edition of the Los Angeles Herald. It tells the story of a tamale man harassed by another tamale man, and notes how “the public smile[d] a sardonic smile and wax[ed] humorous” any time another misfortune fell on street food vendors.

But the unsigned editorial urged compassion, since the “griefs” of tamale men “may be as genuine as those of him who sits upon a throne.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.