California approves math overhaul to help struggling students. But will it hurt whiz kids?

California education officials on Wednesday approved a long-studied overhaul of the state’s math teaching guide, with sweeping changes designed to make the subject more relevant and accessible, stirring debate over whether it will improve poor student achievement or harm learning for 5.8 million public school students.

The 1,000-page teaching framework before the state Board of Education was approved unanimously, culminating a process that has taken more than four years and three versions.

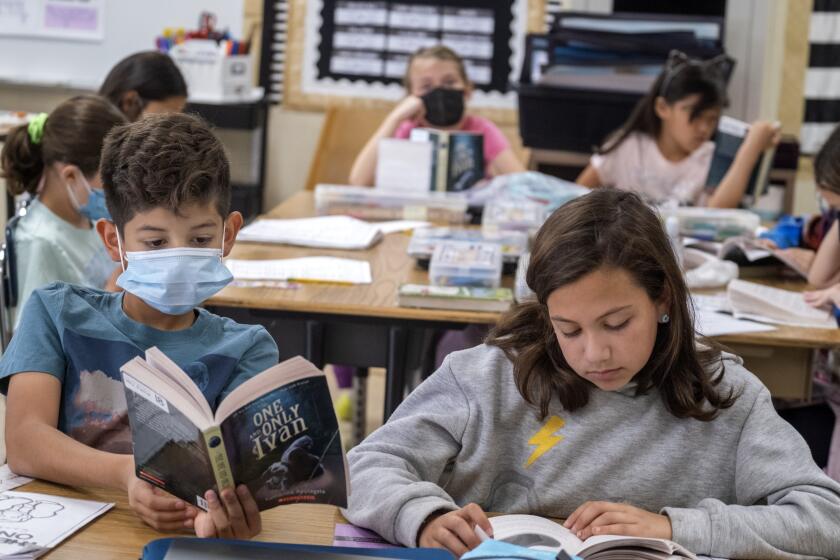

The guide emphasizes replacing traditional instruction with a focus on “big ideas” with the hope that students with varying math skills can work together in the same class for most of their schooling and reverse the state’s low math achievement levels. Critics predict a decline in math achievement from what they see as watered-down curriculum and teaching approaches that they say rely more on ideology than research.

The framework is not a mandate that school districts must follow — and the adopted guide stresses the importance of local control — but the document is influential. Textbooks publishers, school districts and those who train teachers will rely on it, and its influence extends beyond California.

The framework embraces the goal “that all students develop deep skills and a love of mathematics and that many more choose to pursue a science, technology, engineering, or math major in college or pursue other careers that benefit from quantitative knowledge and reasoning.”

The guide presents teaching strategies at all grade levels and connects the instruction of young children to advanced high school math and college-level work. There’s a particular emphasis on “equity” by raising the achievement of Black and Latino students and those from low-income families.

“This is huge,” Kyndall Brown, executive director of California Mathematics Project, said in an interview. “Finally things will start to be able to move forward. We will have a real direction for teaching and learning.” Brown spoke in support of the framework at Wednesday’s board meeting in Sacramento.

One area of criticism that gained steam last week was opposition from faculty members at the University of California and California State University systems.

They noted that the framework draft offered strong support for students choosing data science as a high school math class. The framework also supports other courses outside the traditional progression of classes that lead to calculus, including financial algebra, statistics and computer science.

There is an ongoing debate in academia over whether students should be allowed to take data science instead of Algebra II to fulfill college-admission requirements. These faculty members oppose that substitution, and their position was supported Friday in a vote by a key UC faculty committee.

Even so, applicants for fall 2024 seats will be able to use data science instead of Algebra II while a faculty working group reviews the issue over the coming months.

The final draft of the framework included last-minute word changes to match up with UC policy. The state board also instructed staff to make sure the framework remains aligned to UC.

What has changed?

Overall, the new framework incorporates many changes sought by critics, but still falls short in the view of many — and comes as tests scores are at the lowest levels in years.

The revised document clarifies an earlier flashpoint: Schools and districts can still pursue the goal of advanced math for students using traditional pathways that start with Algebra I and lead to calculus. And there’s more guidance on how to meet student needs.

“While some students have been able to succeed despite various barriers and challenges, that does not mean we can’t open the doors wider so more students can succeed, especially those that have been historically marginalized and shut out,” said Ivan Cheng, a professor in the College of Education at Cal State Northridge.

There continues to be great debate over how data science fits into the picture. Many students who aren’t reaching calculus can benefit from knowing more about analyzing data. But how much math needs to be incorporated into data science, especially within high school courses that would fulfill requirements for applying to the University of California or Cal State?

A majority of Black faculty members in UC science, math, technology and engineering fields said allowing data science to substitute for Algebra II would harm students of color by steering them away from math and science fields and undermine university efforts to improve diversity and equity.

Framework supporters deny that they aspire to dilute curriculum. Instead, they emphasize the need for an early and improved onramp to higher-level math for students of color and those from low-income families. They also want a road map to achievement for students who do not excel at math right away. This means de-emphasizing “tracking,” which groups students by perceived ability or test scores.

The first draft of the framework in particular touted the benefits of grouping students of all math levels together until well into high school. The first draft also de-emphasized calculus as a goal for high school math.

Critics say California’s proposed math framework waters down content in pursuit of equity. Defenders say social awareness will accelerate learning.

Those two changes ignited immediate pushback in 2021— and strong enough to delay the process for at least a year. Critics saw a watering-down of standards — and a counterproductive effort to hold back students who were ready for more advanced math, putting them at a competitive disadvantage in applying for college with students from other states and private schools.

State Board of Education President Linda Darling-Hammond said that if many critics read the framework more closely, they would be reassured. The framework, she said, is about “equity for excellence, not in lieu of excellence.”

The document has evolved to address concerns, she said in an interview, adding the effort is largely an attempt to update math education to account for new knowledge about learning, student needs and the workplace of the future.

“There are multiple ways to get to calculus, and also lots of encouragement for people to think about progress in math — and not about math as just an early tracking system, where some kids are going to get to advanced math and others will not have a chance to do that,” Darling-Hammond said. “Accelerate where kids are ready to accelerate, but also make sure that there are opportunities for others.”

Critics remain dissatisfied.

“Each draft fixed some problems but left many others unchanged,” said Brian Conrad, a math professor and director of undergraduate studies at Stanford. “A major overhaul is necessary.”

Conrad was among those who asserted that the framework pervasively misstated and misapplied research in supporting its concepts. Many changes have been made based on such complaints, but Conrad said the use of citations remains unacceptably sloppy or ideologically tainted. One example, he said, was the use of a flawed and unpublished study — one that did not undergo the standard peer review — to oppose teaching Algebra I in eighth grade.

In comments at the meeting Conrad urged a delay in approval.

Others found the entire document and its philosophy unsalvageable.

“The progressive-education authors of the math framework want students to learn through their own inquiry and self-discovery,” blogged Williamson M. Evers, director of the Center on Educational Excellence at the Independent Institute. “The authors give little emphasis to mastery of facts and standard algorithms” but instead promote “vague, billowy ‘big ideas.’ ”

Framework supporters counter that the big ideas are very much math-focused — and that they are a necessary update to the old way of looking at math as a series of abstract problem-solving skills.

“The learning standards have not changed,” Brown said. “What the framework is talking about is how topics are supposed to be taught.”

Big ideas in sixth grade include patterns inside numbers, fraction relationships and modeling the world.

A look inside the framework

The academics who wrote the first draft — and who continue to lobby for the framework — say students with different math levels could be in the same class learning about the same “big idea,” but they would approach it at their own level. The teacher would challenge the more advanced students with more complex work. This is called differentiated instruction and, to some degree, it happens all the time in class.

Supporters say this structure opens the way to advanced math at all times to students with unrealized potential. But others worry that well-prepared students will be held back — rather than progressing appropriately at their more advanced level.

The framework also speaks of making math relevant to students’ lives and backgrounds. This would be part of the push for equity.

One example cited in the framework is a lesson on measurement that asks students to locate “different places where their relatives lived or that they had heard mentioned.” The students select starting and ending points of immigration and figure out the distances, using the scaling feature on maps. The exercise also offers an opportunity to work on unit conversion to and from the metric system, noting which countries use which system.

Another example, or “vignette,” in the framework stresses the need to build confidence and teamwork among high school students through “math identity rainbows.”

The teacher asks students to “reflect on and share the strengths that you and your teammates bring to the group.”

Each person arranges cords according to individual strengths: Pink is perseverance; orange is numerical reasoning; yellow is communicating; blue is modeling, that is, representing “situations in everyday life mathematically to make predictions and solve problems”; purple is recognizing patterns; white is reflecting, as in: “I know what I’ve learned and what I still need to learn.”

The teacher emphasizes that “all of these are extremely important to being mathematicians and everyone has these qualities, but you have different strengths, right?”

The exercise “provides students with the opportunity to notice that together they are part of a mathematical community.”

Reversing low math achievement

The starting point in the debate centers on low math achievement. Although test scores in math declined sharply during the pandemic, they already were trending downward nationally even before COVID-19.

Comparisons to other countries are flawed, but it’s widely accepted, based on international testing, that the math skills of U.S. students are below average. On national tests, California is below the norm compared to other states: An estimated 23% of the state’s students achieve proficiency in math. There also are wide gaps among groups, with students from more prosperous backgrounds doing better. And white and Asian students have higher test scores than Black and Latino students.

2022 California test scores show 84% of Black students and 79% of Latino and low-income students did not meet state math standards.

It’s challenging to know what is going wrong. The state has approved a succession of math frameworks — the last in 2013 — among steps taken to turn things around.

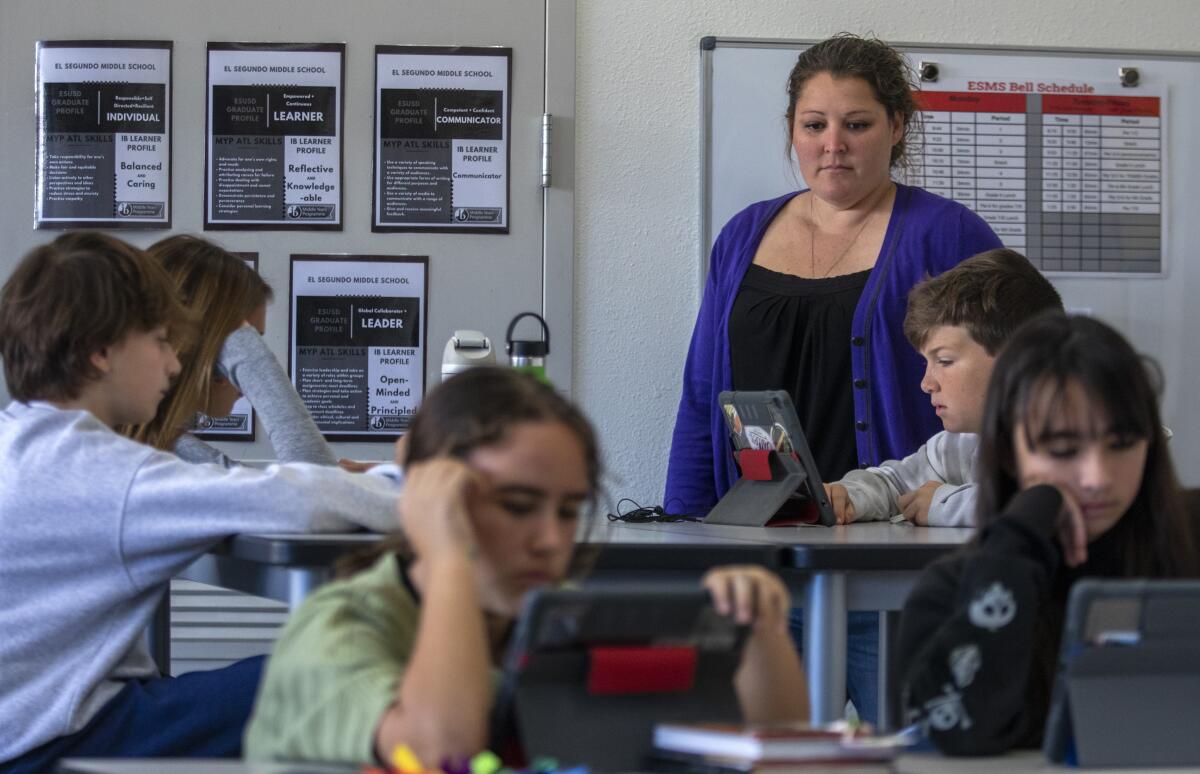

Part of the problem is teacher training, exacerbated by a shortage of teachers with a deep understanding of math. It’s unclear that the 2013 teaching guide was truly carried out at the classroom level across the state, experts said. The same issue could hinder the new framework.

The new framework aligns with those who favor a more thoughtful, potentially slower pacing in math instruction as a civil rights issue. In their view, too many Latino and Black students and those from low-income families have been left behind as part of a math race in which a small number of students reach calculus.

The framework also builds on the state’s existing push toward integrated math, which sets aside the traditional sequence of math instruction: computation, algebra, geometry and ultimately advanced algebra, trigonometry and calculus.

Instead, concepts from all areas are introduced early on and brought together to solve problems — as might happen in a real-world use of math.

The traditional math sequence and teaching practices have worked well for some students. But math-related fields continue to be dominated by white men, supplemented by workers who learned math in other countries or who grew up in a family or culture that emphasized math attainment.

Critics, including many parents, fear the new approaches will limit opportunities for gifted and well-prepared students to reach advanced math, and there will be less time for them to master advanced concepts. Some argue that tracking, as long as it’s not used to exclude students by race, ethnicity or gender, can put students in groupings where their individual needs can be addressed most directly, allowing all students to learn faster.

Another concern is that many top colleges still place an emphasis on whether applicants get to calculus and how well they do in that course.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.