Column: The craziest reparations idea you won’t find in the California task force’s report

At long last, California’s reparations task force will release its final report on Thursday, providing a blueprint for how Gov. Gavin Newsom and the Legislature might go about compensating Black people for the lasting harms of slavery and the ongoing indignities of systemic racism.

By most indications, it will land at the Capitol in Sacramento with the thud of a politically radioactive bomb.

Recent polling from the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California found that just 43% of people in the state liked the idea of the task force even existing. This is true even though, according to the same poll, 80% of residents agreed that racism is a problem in the U.S. — with 42% saying it’s a “big” problem — and about 70% believing it contributes to economic inequality.

Nationally, public opinion is even more anti-reparations.

Only one major poll, from UCLA’s Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies, which has worked closely with the task force, has offered a contrarian point of view. It found that a majority of Californians agree “some form” of compensation is owed Black people. Predictably, though, anything that smacks of cash payments gets far less support.

In a new report, California’s reparations task force calculates how much Black people are owed for racism. It’s at least hundreds of millions of dollars.

And given that the prospect of cash payments — to the tune of potentially billions of dollars in a time of a deep budget deficit — has dominated the public discourse over reparations, it’s no wonder so many politicians are deploying a strategy of avoidance.

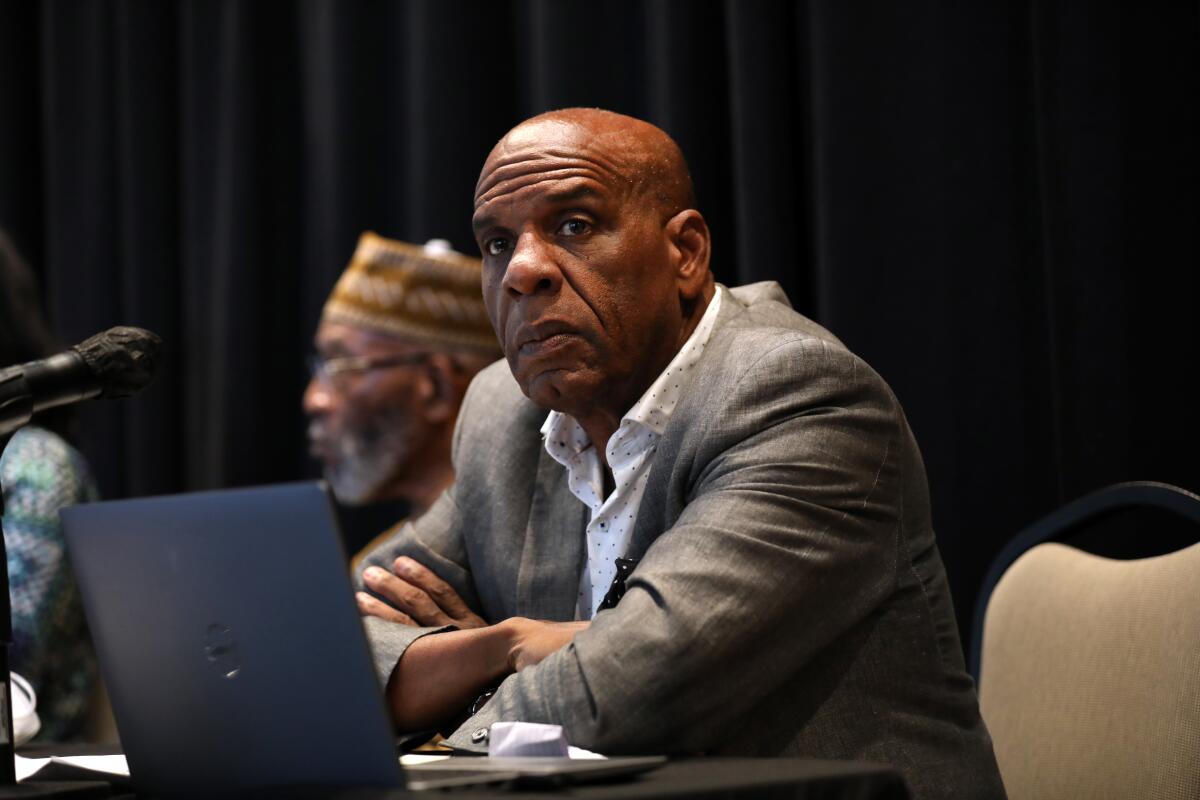

Which is why I suspect that state Sen. Steven Bradford, the Gardena Democrat who is one of only two state lawmakers on the nine-member task force, has been pitching a crazy — or maybe crazy-like-a-fox — idea.

One is primed to become fodder in our endless partisan culture wars, and yet also so logical and mutually beneficial for Californians, that it could persuade politicians who don’t want to talk or even think about reparations to finally do so.

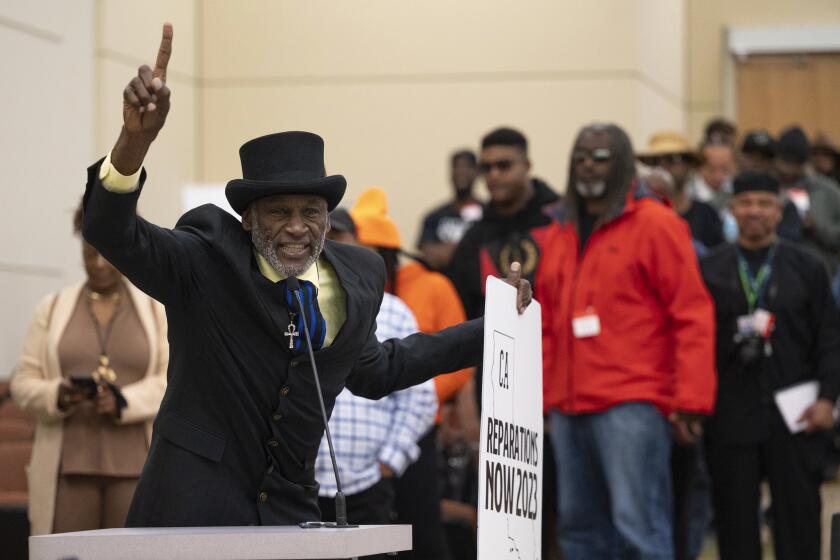

I doubt Bradford’s idea will be included in the task force’s final report. But he floated it during an invitation-only panel discussion earlier this month in West Adams.

“The conversation I had with the governor’s office a couple of weeks ago was that we’re shutting down prisons in the state of California,” he said. “What are we doing with that land? Why don’t we turn that land over to Blacks who have never owned property in the state of California? Why don’t we turn it over to developers and build homes?”

The dozens of mostly middle-aged Black men and women in the room, all clustered around circular tables, sipping on coffee and water with lemon, suddenly burst into raucous applause.

But not me. My mouth dropped open in shock just thinking about the optics of Black people, who are disproportionately in prisons because of bias in the criminal justice system, essentially colonizing the rural, often majority white and sometimes conservative towns where most state prisons are located.

Bradford barreled on, as my mind continued to spin.

“A lot of people are saying, ‘Where’s my check?’” he added, referring to the frequent refrain from attendees of the task force’s meetings over the last two years. “Reparations was never about a check. It’s about land.”

I quickly pulled Bradford to the side after he walked offstage.

“Were you serious?” I asked incredulously.

He nodded. “They lit up with interest,” he said of Newsom’s staff, specifically his chief of staff, Dana Williamson.

Unsurprisingly, Newsom’s office was a bit more circumspect when I asked about their conversation.

“Successfully interpreting Dana’s bright poker face remains elusive for even her closest colleagues and friends,” a spokesperson told me via email. “The governor looks forward to reviewing the final report.”

Bradford doesn’t seem to be willing to let this go, though.

“Why can’t we [let] African Americans set up businesses and build homes there? Do agriculture projects, whatever the case may be and let that be Black-owned, Black-controlled?” he told me. “Because, again, generational wealth is not through money, it’s through land.”

In some ways, this makes perfect sense.

California has been shutting prisons for years. And the state likely will continue to do so for years to come, as the number of people behind bars continues to decline and as complaints about vermin, infrastructure problems and often deadly conditions continue to mount about where those remaining inmates are held.

In his time as governor, Newsom has ordered the closure of several prison yards and three prisons, including the Deuel Vocational Institution in Tracy, the Chuckawalla Valley State Prison in Blythe and the California Correctional Center in Susanville.

It’s the last of the bunch that was perhaps the most controversial. Defenders of the California Correctional Center — or CCC — sued the state, prompting a judge in rural Lassen County to issue a temporary restraining order that halted the closure.

Susanville officials were adamant about not losing 1,000 prison jobs, saying it would lead to economic ruin. That set up the narrative of a mostly white, conservative, already dying Northern California town arguing that its very survival depends on the incarceration of Black and Latino men from Southern California.

“The court is deciding whether a form of bondage, a form of cruelty, is going to continue based on the personal financial benefits of the people around the prison,” Shakeer Rahman, a Los Angeles-based attorney who represented inmates who signed the amicus brief, told The Times. “At every single turn, the judge and the city have silenced the voices of our clients in order to keep marching on in this decision-making that treats them as a source of revenue.”

Gov. Gavin Newsom and California lawmakers need to say where they stand on reparations for slavery and how the state should correct the injustice and discrimination of the past.

A provision tucked into last year’s state budget eventually settled the case, forcing Susanville to accept that the CCC will indeed close — and with the deadline at the end of this month, it is mostly closed.

But the racist narrative of what happened lives on. So, in some ways, giving Black people the land where the prison once operated as reparations could be seen as poetic justice. It also could be seen as a gift of trauma.

Bradford readily admits that state prisons, as a rule, aren’t in “the most desirable areas” in California. But it’s still land that isn’t being used that can be economically controlled by Black people, whether it’s for industrial buildings or cannabis grows.

“They don’t have any plan for it right now,” he said of state officials. “That’s why I gave them a suggestion of what they could do.”

This silence from state officials is one of Mallory Crecelius’ biggest fears. The interim city manager of Blythe, a shrinking town in Riverside County along the Colorado River, told me she hasn’t heard anything about potential redevelopment of Chuckawalla Valley State Prison.

“As far as we know, the state has no plans to do anything with the site, which would be the worst-case scenario,” she told me. “We lose the prison, and then we lose any ability to repurpose it.”

While many have been focused on keeping the prison from closing in 2025, others are trying to figure out what can be done. The site is remote, some 20 miles out in the desert from downtown Blythe, and sits right next door to another state prison.

So reparations? An influx of Black people?

“We’re open to ideas,” Crecelius said, “because we really do need to figure out a way to replace the jobs that are going to be lost.”

Somewhat surprisingly, Susanville Mayor Quincy McCourt had similar things to say when I asked him about reparations.

“I’m 100% open-minded to anything. We, as a community, are 100% open-minded to anything, whatever the idea is,” he told me. “And if the state is discussing what to do with either the facility or the land, we all benefit from including the key stakeholders in Lassen County and Susanville. We need to be in those discussions.”

So is Bradford crazy or just crazy like a fox? Should reparations only include often-discussed things like free college tuition, housing assistance, interest-free business loans and, yes, cash payments? Or is there room for new and creative ideas that could solve many of California’s problems at once?

Only time will tell.

“We’re going create a working group after the final report is out,” Bradford told me, “and we’re going to try to come up with a legislative package that we can hopefully get across to the governor’s desk.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.