LAUSD’s $18.8-billion budget is flush with COVID-19 funds for one more year, but then what?

The Los Angeles school board Tuesday approved an $18.8-billion budget that includes the last major pandemic aid — government funding that will disappear in future years, putting jobs and services to students at risk.

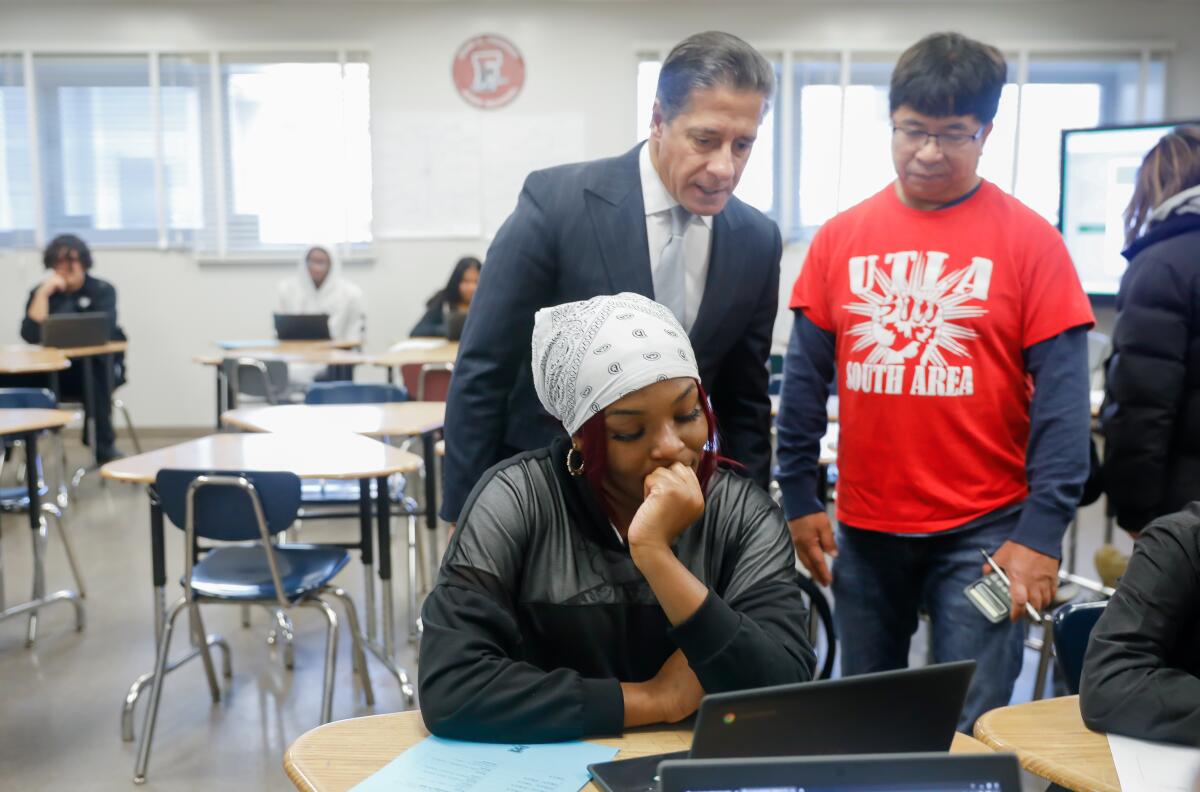

Schools Supt. Alberto Carvalho said the district is prepared to manage the transition without layoffs — and he also pledged improved student support through lower class sizes, additional counselors and increased mental health services.

But Carvalho added there will be “pain” for employees. The district must contract by more than 2,000 full-time positions that had been funded by the influx of state and federal aid in response to COVID-19 and will do this through attrition and eliminating some unfilled positions. Many of the district’s 75,000 full- and part-time workers, including about 25,000 teachers, will have to change jobs or job locations.

In the big picture, said Carvalho, the budget is centered on “empowering student achievement,” especially by helping the “most fragile schools” and “most fragile students.”

The district’s central budget — the general fund — will be $12.9 billion, but separate funds contribute to the $18.8-billion figure, including for adult education, the student body fund and construction projects.

Debate over the budget has sparked public passion over Carvalho’s overhaul to an early reading and math program called Primary Promise and over funding for school police.

Approved unanimously by the seven-member board, the budget uses one-time funds “where appropriate,” Carvalho said, but backs away from that approach “into sustainable, more long-lasting funding streams.”

What will happen to Primary Promise?

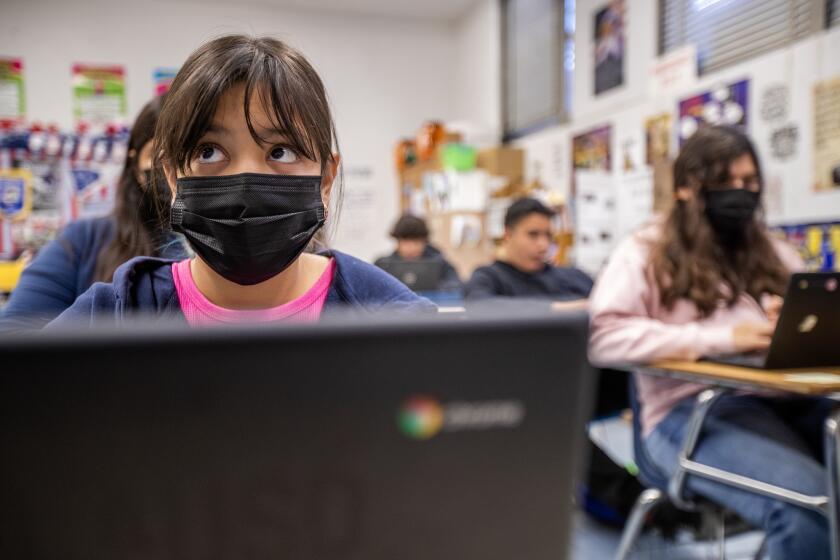

Primary Promise targeted struggling students in kindergarten through third grade with daily small-group tutoring from a teacher and an aide for 30 minutes in math, reading or both. Their progress was monitored every two to three weeks, with instruction adjusted accordingly. The intervention program was highly touted by former Supt. Austin Beutner and by administrators and had widespread support from parents and teachers.

Carvalho’s revamping of the program — cutting back sharply on these intervention positions at elementary schools — angered its supporters. His plan also added literacy help to middle school and expanded training and coaching for classroom teachers.

On Tuesday, Carvalho presented an updated plan. For one transitional year, he authorized an additional $40 million — using unspent federal antipoverty funds, which will spare some schools the cost of paying for an academic intervention specialist.

Schools that lost an interventionist under the Carvalho overhaul — but decided to use their discretionary funds to replace the teacher — will be reimbursed for the cost for a year. The reorganized intervention program will begin this fall and will include additional teacher training this summer.

Carvalho also restored regional supervisors who had been overseeing mental health professionals who work at schools. His earlier plan had been to move all but 18 of 75 supervisors to campuses to fill school-level vacancies. He said that, instead, he will retain 30 supervisors.

In touting the new budget, Carvalho also focused on the large salary increases for employees and his pledge to maintain special programs for Black students.

What else does the budget include to address pandemic academic setbacks?

The budget continues to include funding for on-demand, online tutoring and expanded summer school. In addition, there’s more than $80 million to expand the school year by three days. And the controversial “acceleration days” — optional extra learning time — will return during a portion of the three-week winter break.

L.A. Unified worked to make optional “acceleration days” work for students and help them raise grades. But most students opted for a full spring break instead.

Some budget elements relate to the contract settlement reached with United Teachers Los Angeles in March. Under that agreement, the maximum caseload for a secondary-school counselor drops from 750 to 700.

The contract also requires the district to provide a college counselor or college advisor to every high school with at least 900 students over the next two years. Schools of that size have sometimes had to do without. Similar changes apply to providing schools with psychiatric social workers, psychologists and attendance counselors.

Class sizes at 100 district-selected schools will drop by one student in 2023-24 and by one additional student the following year. A one-student reduction will expand to all campuses in 2024-25.

Is the school police budget going up or down?

It depends on how you look at it.

In July 2020, the school board voted to cut $25 million from the department’s $70-million budget, which activists saw as the anticipated first step toward eliminating the department.

But cuts of that magnitude were never realized. By December of 2020, officials said the actual police budget had been $77.5 million — not $70 million. Therefore, the cuts at that time took the budget down to $52.8 million, officials said this week. Activists are now looking at a police budget for next year of $58.5 million.

Deputy Supt. Pedro Salcido said Tuesday that the action in 2020 resulted in cutting department staffing from 511 to 396 and it will drop further under the new budget to 388.

The subsequent increases are related to higher salary and benefit costs and inflation elsewhere — not increased police presence or staffing, Salcido said.

Activists challenge L.A. Unified superintendent’s support of school police, as well as school board members who reduced the police budget but did not disband the agency.

In the current year, the police budget reached even higher — to $62.6 million because of spending to update and equip the vehicle fleet.

Tre’Niece Thomas, a ninth-grader at King/Drew Magnet High School, criticized Carvalho for asserting there was no increase in the police budget.

“Didn’t you promise us that you would not raise the budget and yet you still plan to?” she said. “You know you are a liar.”

Tanya Ortiz Franklin was the lone board member who voted against the contract settlement with the police officer and police manager unions, which also was on Tuesday’s agenda.

“My vote isn’t about individual police officers not being deserving of a raise or healthcare benefits — particularly in light of the cost-of-living increases in Los Angeles — but I’ve committed to police-free schools because I don’t believe dollars dedicated for public education should be spent on law enforcement,” Franklin said.

Several district parents spoke strongly in favor of increasing the presence of police because of crime and conflict in and near schools. The head of the administrators union, Nery Paiz, spoke of too many unchecked assaults against staff and students.

“There is hard data with real-life incidents across the district,” said Paiz. “A police-free district is a worse idea than the original reduction. Learn from the costly mistakes borne by the students, staff and district.”

Why is L.A. Unified taking out $500 million in loans and how is the district able to do it?

The loans are called certificates of participation and must be paid back over time out of the general fund — the same money that pays for salaries and programs.

Officials said the borrowed money — which is equal to about 4% of the annual budget — will include cybersecurity protections in the wake of last year’s damaging cyberattack. The money also is expected to speed up the creation of an electric bus fleet, which could recoup some of the expense in operating savings over time. Some of the money is slated for increased campus security features to limit access to intruders.

The debt service will range from $14.7 million to $49.7 million per year at an estimated interest rate of 6.5% through 2038.

Is the district doing well financially or not?

The budget report contains some sobering words:

“L.A. Unified continues to have a structural deficit whereby in-year expenditures exceed in-year revenues. As revenues continue to decrease due to enrollment decline, expenditures have not been reduced proportionately.”

Moreover, the budget “includes the draw down of one-time fund balance” that is being used to cover ongoing costs.

By end of 2025-26, the budget report predicts an ending balance of $10.6 million, which is minimal in the mammoth district.

This year’s budget includes the infusion of about $900 million from the last tranche of pandemic aid. There’s also $457.1 million of new state revenue from the Expanded Learning Opportunities Program, a grant that may or may not be provided in future years.

Can L.A. Unified afford the large employee raises that are set to go into effect?

Employee raises approved to date represent a commitment of $4.2 billion through 2025-26, officials said. Carvalho said these raises can be funded and that the district must offer competitive and fair salaries in high-cost Los Angeles.

The settlement comes after LAUSD teachers joined a three-day strike with support staff last month. It includes plans to reduce class size and increase student mental health services.

The district projects a positive ending balance for the next three budget years, although such projections involve a lot of educated guesswork. Much will depend on the health of the state economy.

What’s going on with the multibillion-dollar liability for healthcare benefits for retirees?

The most recently announced calculation set the district’s unfunded liability for retiree health benefits at about $10.2 billion. This debt will not drag the district under, but retiree health needs could severely restrict the district’s ability to pay salaries of active workers and provide robust academic programs.

Officials have been trying to bolster a trust fund to offset these costs. This year’s budget contains $211 million for that fund, but only $33 million is set aside for each of the following two years — a large reduction from previous plans to reduce this looming budget gap.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.