A shop owner said he killed two robbers. A detective believed him. Then it all fell apart

Inside the Downey stereo shop, police found two dead men and a live one with an explanation.

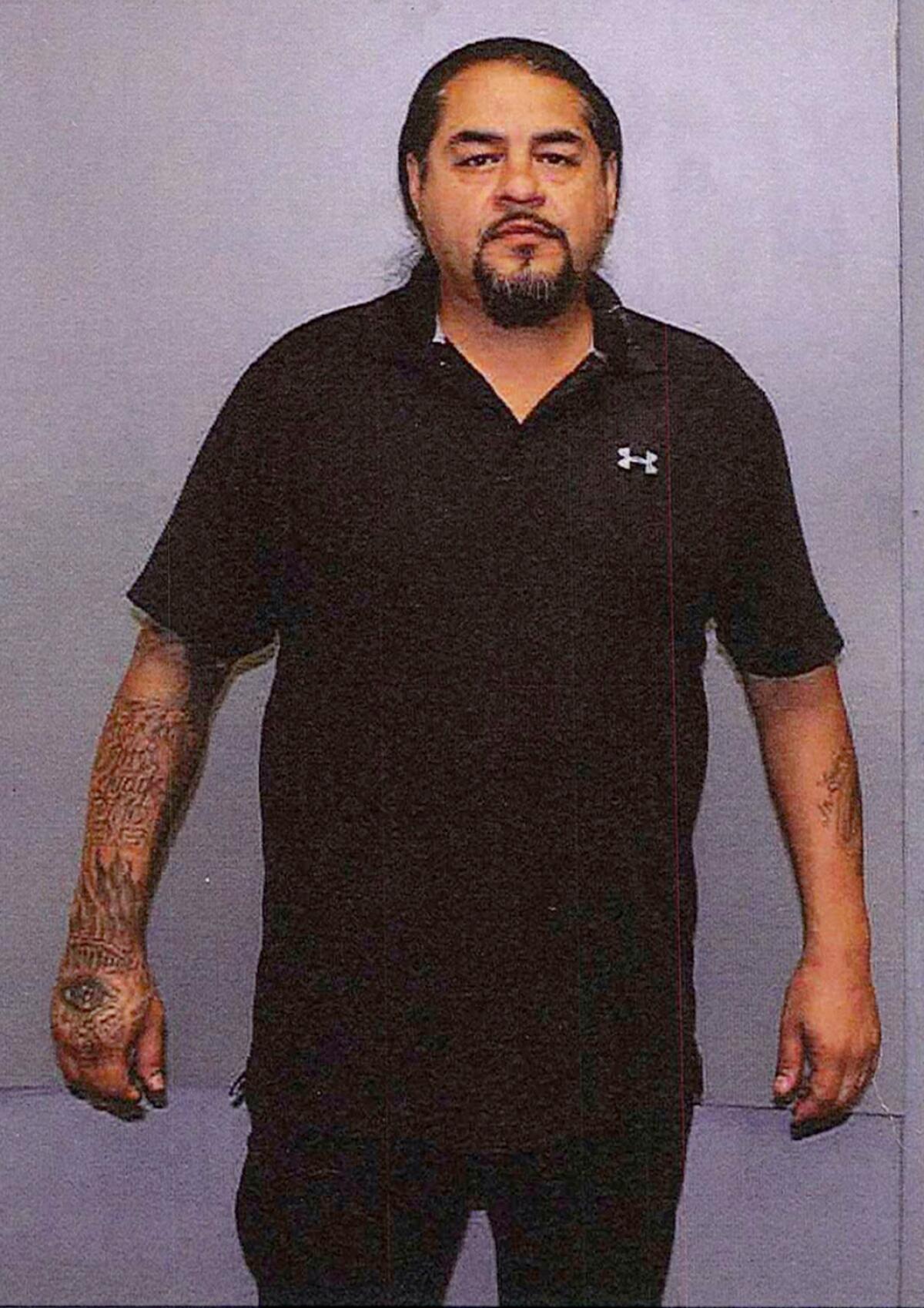

Jorge Valencia said three men had come to his shop to rob him. He drew first and shot two of them dead. The third man, who took a bullet in the chest, ran off.

But his story soon began to unravel. Valencia, it emerged, was being investigated by the Drug Enforcement Administration, which had tapped his phone and monitored his shop with a hidden video camera.

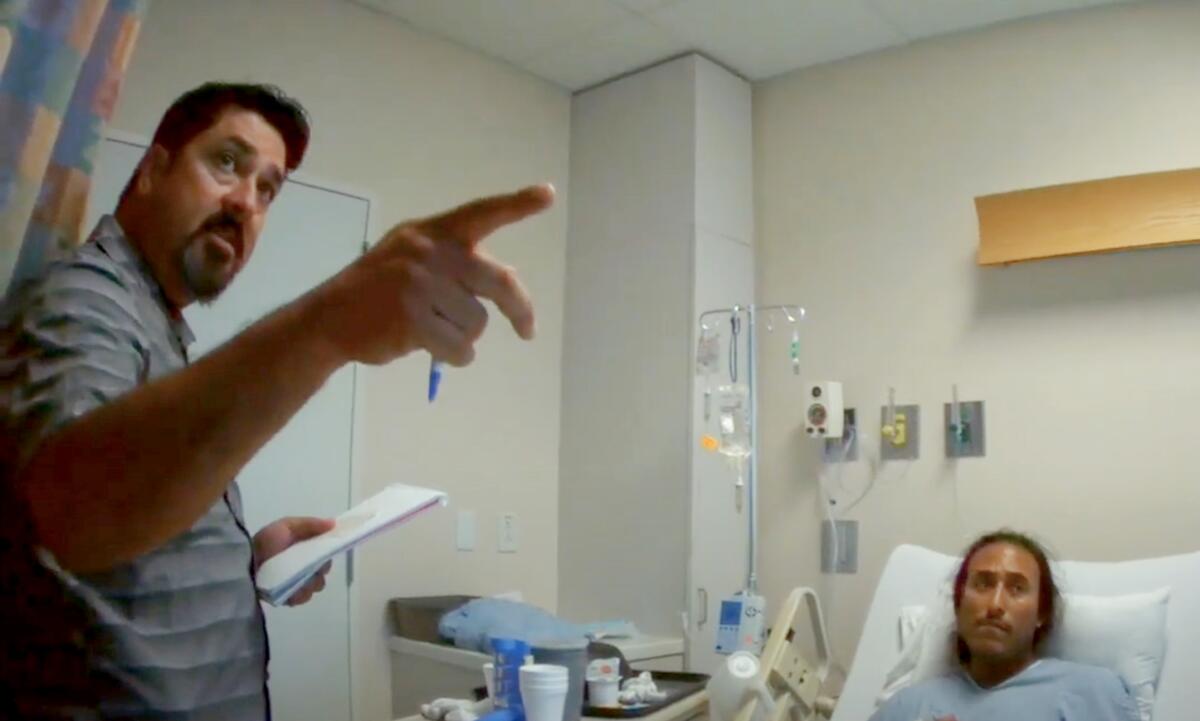

The DEA’s evidence contradicted key parts of Valencia’s account. Yet the Downey detective investigating the homicides remained convinced Valencia had acted in self-defense. So he arrested the third man who’d entered Valencia’s shop — in his hospital bed where he was recovering from surgery.

Under a legal theory that holds people liable for murder if they set out to commit a violent act that results in death, Fernando Garcia was charged with the murders of his two friends.

The case went to trial. When evidence from the DEA wiretap came out that undermined the robbery theory, a judge threw out the case and released Garcia from jail.

Garcia then sued the detective who arrested him, Carlos Bejines, alleging the Downey policeman had disregarded evidence that suggested he was not the perpetrator of a robbery but the victim of an ambush.

The civil case, which a jury heard in downtown Los Angeles in early May, was a painstaking examination of how police investigate the chaos of violent death.

Bejines’ attorney stressed to the jury that the question before them was a narrow one: Not whether Garcia was innocent, but whether it was reasonable for the detective to have believed Garcia had committed a crime based on what he knew at the time of the arrest, just four days after the homicides.

The evidence was conflicting and did not come out all at once. Now that the case is over, The Times has access to records Bejines says he had not yet seen when he placed Garcia under arrest. This story unfolds along the timeline the detective described in his testimony.

Every step of an investigation is a conscious choice: Whom to interview. How broad a net to cast. Who is seen as a suspect and who is considered a victim.

Garcia’s case illustrates how this process can go terribly wrong. He was jailed for nine months on charges a judge eventually dismissed. The investigation was so compromised — by sloppiness, by a detective’s tunnel vision — that the truth of what happened may never be known.

Garcia’s attorney, Anthony Willoughby, said he has never in his 34 years of practicing law seen a detective shade, distort and bury facts like Bejines did.

“He decided to be judge, jury and executioner,” he said.

*

On the evening of June 12, 2017, Bejines was called to First Class Car Audio on Rosecrans Avenue in Downey. He had 17 years of experience with the Downey Police Department, but this would be his first time taking the lead on a murder case.

Oscar Nungaray’s body lay on the floor of a back office. Edgar Luna’s was in the hallway, a Beretta under his hand. Twenty-eight shell casings of different calibers littered the office and the hallway.

That night, Valencia gave a statement to Bejines and another detective, Paul Hernandez: He was at his desk, getting ready to close for the night, when three men walked into his office. One of them made a motion that showed a gun in his waistband.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

“I grabbed my gun and I just like, right away, cocked it and I just — when I took it out, you know, like, we just started shooting at each other, like, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom.”

Valencia said bullets flew at him from three directions.

“I know it’s traumatizing, three people shooting at you, bro,” Bejines said. “I can’t even imagine what you went through.”

There was just one other person in the shop, a friend, who was in the bathroom when the shooting broke out, Valencia said.

Then Bejines did something unusual: He took Valencia back to the crime scene to demonstrate how the shooting had unfolded. The detective testified he did this so Valencia could get “all his ducks in a row” and be sure his statement aligned with the physical evidence, the layout of the room, the placement of the casings, the angles of the bullet trajectories.

Valencia told Bejines the third man, the one who was shot but escaped, was a Black man with an Afro.

Bejines went to St. Francis Medical Center in Lynwood, alerted that a man had been admitted with a gunshot wound to the chest. Garcia, who is Latino and who does not have an Afro, said at the civil trial that the detective was at his bedside when he awoke from surgery.

When Ezequiel Romo came home to Panorama City after 18 years in prison, he didn’t like what he saw. He told another veteran of his gang, Blythe Street, he was going to “clean out house.”

Garcia and Bejines recalled the conversation differently. Garcia testified that he told Bejines he’d gone to pick up money Valencia owed him, but the detective just “smirked at me and said, ‘You sure?’ ” Bejines asked if he’d gone there to rob someone, Garcia testified.

Seeing the detective had made up his mind, Garcia refused to talk to him. “I’m telling him the truth,” Garcia testified. “He wasn’t believing me.”

Bejines testified that Garcia told him he’d gone to Valencia’s shop to look at some rims when a Latino man with a bald head and tattoos shot him with a chrome handgun. At this point he considered Garcia “more of a victim” than a suspect, Bejines testified.

Two days after the homicides, a DEA agent came to the Downey police station with a key piece of evidence. Lindsay Shaffer had been investigating Valencia for the last six months. Suspecting him of distributing methamphetamine and cocaine in Downey and Compton, agents got a judge’s permission in March 2017 to tap Valencia’s phones, wiretap records show.

Federal prosecutors say Gabriel Zendejas Chavez, a criminal defense attorney who once taught English, connected the Mexican Mafia’s bases of power in prisons, jails and the streets of Southern California.

Shaffer had come to Valencia’s business the night of the shooting and told Bejines of “an ongoing investigation of the location,” the detective recalled. He said he assumed it was a narcotics case but didn’t press her for details.

Two days later she gave him video from a camera the DEA had mounted on a pole facing the shop. Watching it at the police station, Bejines saw two cars pull to the curb outside the business, first a white Mercedes-Benz sedan and then a dark-colored Toyota Avalon. The Toyota parked directly in front of the Mercedes, boxing it in.

Garcia got out of the Mercedes; Luna, 38, and Nungaray, 44, stepped out of the Toyota. Luna got into the passenger seat of the Mercedes, remaining there for a few seconds. Then Valencia opened the front door of his shop, looked at the three men and returned inside. Garcia, Luna and Nungaray followed him in.

A minute later, Garcia ran out the front door and turned, his right hand extended. A plume of smoke emerged from it.

Carmen Rodriguez was the victim of an assassination ordered by others in the Mexican Mafia and carried out by her husband’s underlings.

Before the police arrived, eight additional people could be seen leaving Valencia’s shop.

Bejines said the DEA’s footage “put a question in my mind”: Why had Valencia said he was sitting at his desk when the men barged in? And who were all those people leaving the shop, when he’d said it was only him and a friend inside?

The detective testified that he and his partner confronted Valencia about the discrepancies. The tape of the interview suggests otherwise.

“Everybody goes through some traumatic stuff, and your brain does weird things when that happens,” Hernandez said on the tape. “That’s why we’re showing you this video to refresh your memory.”

‘Meeting with the enemy’: Was the leader of the Mongols motorcycle gang a double agent for the feds?

Three years after a federal jury convicted the Mongols of racketeering, a recording surfaced suggesting their leader had a secret relationship with the agent who led the investigation.

Valencia admitted he’d lied about the other people in his shop but said they were customers and friends who “had nothing to do with this.”

“Perfect,” Hernandez said. “That’s what I need to hear. We just need to hear it from their mouth, not yours.”

Bejines chimed in at another point, “We’re not trying to scalp you. We just want your statement to get stronger.”

After showing Valencia the video, Bejines asked Valencia if he wanted to “revisit” a lineup he’d shown him a day earlier that included Garcia’s photograph. Valencia hadn’t identified anyone as resembling the third assailant.

The trial of a former L.A. gang member for the deaths of 10 in a 1993 fire was a step back to a time when gangs turned entire blocks into drug bazaars.

“You think you can get it now?” Bejines asked.

“I don’t know, I could try,” Valencia said. “But remember I told you he looked Black, he had long hair? On the video it shows —”

Hernandez interjected: “Well he’s pretty dark in that video to me.”

“Yes,” Valencia said. “So he looks Black, right?”

“No, well, he looks — to me he looks like a dark-skinned Hispanic guy, but whatever you’re thinking…” Hernandez said.

He thought he was going to meet a woman he’d been messaging online. But Bryan Cojon Tuyuc drove into a trap set up by the street gang MS-13, detectives say.

Then Valencia recalled an earlier robbery at his shop in which he said he shot one of his assailants. “I didn’t get arrested. I didn’t go to jail.”

“Just like this time,” Hernandez said.

Four days after the shooting, Bejines returned to St. Francis Medical Center. “I’m here to advise you that you’re under arrest,” the detective told a bewildered-looking Garcia.

Garcia was charged with attempting to murder Valencia and murdering Luna and Nungaray under what is called the provocative act theory of liability. Prosecutors alleged that in trying to rob Valencia, Garcia had set off the violence that caused his friends’ deaths.

On the stand in the Stanley Mosk Courthouse, Bejines recounted the evidence he’d considered in making the arrest: His interviews with Valencia; Garcia’s admission he’d gone to the shop; the video that showed him shooting at the store; a call from someone who introduced himself as Garcia’s lawyer.

The person described the shooting as “a drug deal gone bad,” Bejines testified. He did not record the caller’s phone number but took down the name he’d given and “googled him” to confirm he was a real attorney, he said.

Garcia denied the lawyer had ever represented him.

Bejines said he also considered the criminal history of both Garcia and Valencia: Valencia had never been found guilty of a felony, he said, while Garcia had “an extensive criminal history” that included four felony convictions.

Bejines testified that he was unaware of previous investigations into Valencia by his own department that did not result in convictions.

Police reports that Willoughby obtained through a public records request show that in 2012, a man walked into the Downey police station’s lobby with a bruised face and swollen lips.

After being sold a computer that didn’t work, the man had confronted Valencia at his shop. Valencia and six other men began beating him, he said. According to the man’s statement, Valencia drew a gun from his waistband, pointed it at his head and accused him of working with the police, saying, “You f— pig. I’m going to kill you.”

The man said Valencia pistol-whipped him and another man put a revolver in his mouth and pulled the trigger. The gun didn’t go off.

In 2010, another report says, a man told Downey police that he saw Valencia point a gun at a woman’s head in his shop. According to the police report, the woman ran across Rosecrans without shoes and told the man, “Help me. I’ve been raped.”

Valencia told an officer no women had been in his shop that night.

In 2009, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives and the FBI raided Valencia’s business, seizing cocaine, 12 rifles, five handguns and 14 explosive devices, according to an article in the Downey Patriot. Valencia was arrested that day carrying a gun, the newspaper reported.

There is no record of Valencia being charged in any of the incidents.

The DEA recorded 10 calls that Valencia made in the eight hours leading up to the shooting. They were summarized in a 15-page document Willoughby described as “the one most critical piece of evidence in the case.”

It would throw into doubt the prosecution’s theory of a robbery gone wrong. Without it, Willoughby said, Garcia would probably have spent the rest of his life in prison.

It nearly did not come to light.

The document was what the DEA calls “line notes” — not a verbatim transcript of every word captured on the Valencia wire, but a summary written in real time of what agents overheard.

When Bejines looked at the document, redacted in parts and littered with names he did not recognize, he found it “cryptic,” he testified. “I couldn’t make heads or tails of those notes.”

Willoughby asked if he had tried to clarify their meaning with Shaffer. He hadn’t.

“A double murder just occurred, and you weren’t interested in picking the brain of the DEA agent monitoring the wire?” Willoughby asked, incredulous.

“No, sir.”

The agent, Bejines said, “had her biases against Mr. Valencia.” In fact, she believed Valencia should be arrested for the murders of Luna and Nungaray and the attempted murder of Garcia, he testified.

Bejines did not record when he received the line notes. He didn’t document getting them at all. “We don’t document things that don’t make sense,” he testified.

“In an abundance of caution,” Bejines said, he submitted the line notes to the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office. This is important because prosecutors must turn over evidence to defendants in a process called discovery — particularly evidence that undermines the prosecution’s case.

Steven Schreiner, the deputy district attorney who prosecuted Garcia, could not recall in a deposition when he got the line notes. He said he believed it was close to trial, which began in February 2018.

Willoughby told The Times he got the line notes in November 2017 — and not through the discovery process, but from a source he would describe only as “an angel looking out for my client” who “felt an injustice was occurring.”

On the last day of Garcia’s criminal trial at the Norwalk courthouse, Willoughby called Garcia’s girlfriend, Yolanda Hernandez, to testify about a deal she’d brokered with Valencia.

Two weeks before the shooting, she told the jury, Garcia, Luna and Nungaray had asked if she knew anyone who would buy 12 pounds of marijuana.

Hernandez thought of Valencia. Growing up in Compton and with family in Valencia’s gang, Tortilla Flats, she knew of his reputation as “a dope dealer,” she said.

At Valencia’s shop, she introduced him to Garcia, Luna and Nungaray, who handed over the marijuana. Valencia promised to pay $13,000, but over the next two weeks, she said, he balked at repayment.

The evening of June 12, Valencia called her and said Garcia, Luna and Nungaray could pick up the money at his business, she testified. She told Garcia to go to his shop.

Schreiner, incredulous, asked why she had waited nine months to come forward with this story. She said she did not trust the Downey police, whom she believed Valencia had bribed, or the prosecutors who “let him walk.”

“He’s being protected from you guys,” she told Schreiner.

To this point, the prosecutor had asked Judge Robert Higa to exclude the wiretap evidence from the trial, saying its only purpose was “to paint Mr. Jorge Valencia, the victim in this case, as a drug dealer.”

Yet as he grilled Hernandez, Schreiner began reading from a transcript of her calls with Valencia.

After her testimony, Higa asked the jury to step outside. Then he turned to the lawyers. “The transcripts for the wiretap seems to justify that — corroborates everything she said about them going over there and that Mr. Valencia was involved in this transaction,” the judge said.

Schreiner argued the taped calls did not disprove that Garcia had gone to Valencia’s business with violent intentions. “I have to make this point: No one is entitled to collect a debt at gunpoint. Nobody. Even if there is a legitimate debt. That is robbery.”

Higa, unpersuaded, dismissed the case.

In his deposition, Schreiner said he was unaware that a deputy district attorney in the office’s Major Narcotics Division wanted to use the recordings to prosecute the wiretap’s targets for the murders of Luna and Nungaray, the attempted murder of Garcia, conspiracy to murder and gang conspiracy.

Schreiner did not know his office was even involved in the wiretap until Willoughby told him. “I thought it was a DEA thing,” Schreiner said.

For nearly six years, Garcia did not tell the whole story — or, depending on whom one asks, the true story — of what happened inside First Class Car Audio.

Earlier this month, the 39-year-old testified that he, Luna and Nungaray went to the shop to pick up $13,000 Valencia owed for the marijuana. “None of us had any weapons,” he said.

Valencia opened the door of his shop and said, “Hey, I’m George. Come inside.” They followed him down a long hallway to an office. Once they sat down, Garcia testified, “All I see is a chrome object behind George. Bang, bang, bang. And I ran out.”

As he fled back through the hallway, Garcia said, a man stepped in front of him and shot him in the chest. Garcia testified that he wrestled the gun from the man. Hearing gunshots behind him and someone yelling, “Get that fool,” he turned and fired, he said.

He described to the jury the nine months he spent in jail, facing a life sentence. He was behind bars for the holidays. He missed his children’s birthdays.

“I know that I was innocent, innocent,” he said. “And the person who did this to my friends is still outside.”

No gun was found on Nungaray. Willoughby maintains that someone planted the Beretta on Luna after he was killed.

Based on ballistics testing, “at least four” guns were fired inside the shop, Bejines testified at the criminal trial. His investigation was so bungled, it seems no one will ever know what happened. The guns were swabbed for DNA, but the detective could not recall ever getting the results. None of the weapons were fingerprinted.

In making his case to the jury, Bejines’ attorney, Michael Allen, had only a low bar to clear. Based on what the detective knew at the time of the arrest, did he have probable cause to believe Garcia had committed any one of seven crimes: possessing marijuana for sale, carrying a gun as a felon, carrying a gun in a public place, shooting into an occupied building, assault, attempted robbery or murder?

The jury’s answer, overwhelmingly, was no. They voted to award Garcia $1.07 million in damages. Finding that Bejines had acted with “malice, oppression or fraud,” they decided he should pay Garcia another $50,000 from his own pocket.

Today, Bejines is a school resource officer at Downey High. The 23-year law officer insisted his transfer out of the detective bureau was routine. Willoughby scoffed. That Bejines had gone from investigating murders to “basically a crossing guard” showed his department “knew he was bad,” he said, “but they had to circle the wagons.”

Dorian Munoz, a spokeswoman for the city of Downey, declined to comment.

Valencia was never arrested in connection with the shooting, Bejines said. Nor has he been prosecuted for any of the drug crimes investigated through the wiretap. He never testified in the cases, criminal and civil, that stemmed from the shooting.

The Times could not reach Valencia for comment. A woman who answered the door at the house where he once lived said she did not recognize the name.

Willoughby said that if Downey police wanted to do the right thing, they’d reopen the case. “There’s no statute of limitation on murder,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.