The foundation: Inside the LAPD’s secretive, multimillion-dollar private funding arm

The Los Angeles Police Department and its multibillion-dollar budget were under intense public scrutiny in the spring of 2020.

The COVID-19 pandemic had greatly reduced city revenue amid some of the largest and most destructive street protests in decades. The LAPD was being accused of exacerbating the unrest and bungling its response. Activists and politicians were calling for the department’s funding to be slashed in favor of social services for the homeless, mentally ill and poor.

Behind closed doors, the money from private donors kept coming.

“I wanted to share that since May 28th, we have received more than $48,000 in online donations in support of the Department — a record for our organization and unlike anything we’ve ever seen,” Dana Katz, head of the private Los Angeles Police Foundation, wrote in a June 9, 2020, email to LAPD Chief Michel Moore.

Katz wrote to Moore again a couple of weeks later, this time with a list of donors who would be taking part in an exclusive call with him that she had arranged. Katz told Moore it “would be great” if he would brief the philanthropists and corporate bigwigs on the recent protests, the department’s plans for reform and the potential negative effects of “defunding” the police.

Moore responded with a simple “thanks.”

It wasn’t the first time Katz had tapped Moore for a fundraising initiative.

The 25-year-old Los Angeles Police Foundation enjoys regular access to top LAPD officials, working closely with them to craft fundraising campaigns and host meetings with L.A.’s mega-rich and other philanthropic and corporate donors, a Times investigation has found.

Just as politicians spend quality time with big campaign contributors, Moore and other police officials regularly assist the foundation. In the quest to secure private cash for the LAPD, they make the case to potential donors that the agency’s already robust taxpayer-funded budget is insufficient for its needs, according to thousands of pages of emails and other public records obtained by The Times.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

The foundation’s donors are rarely disclosed publicly, although they have an effect on how the LAPD provides for public safety, with a majority dictating how the department can spend the money they give.

Since the rise of the “defund the police” movement in 2020, such nonprofits have faced criticism nationwide. The L.A. foundation is no exception.

On a near-weekly basis, local activists call in to virtual meetings of the Los Angeles Police Commission — the LAPD’s civilian oversight board, members of which have also worked with the foundation — to lambaste it for approving foundation-funded initiatives.

They allege that the foundation’s donors are buying influence and special treatment from the LAPD — or at least trying to — by providing it with expensive technology and equipment that the agency uses to disproportionately surveil and harass communities of color.

Police officials, foundation leaders, donors and their supporters reject those claims as baseless attacks from a radicalized left that threatens to undermine public safety by stripping resources from law enforcement. If anything, they say, private funding for the LAPD reduces the amount of public funds that are designated for law enforcement and helps pay for cutting-edge training and crime-fighting technology.

Moore and Katz acknowledge their close working relationship but say they follow strict ethical standards and all applicable nonprofit laws. They say donors do not receive special treatment.

“My integrity, the integrity of this organization and the integrity of the LAPD — because it reflects on us — are of the utmost importance,” Katz said. “There’s no quid pro quo.”

Katz said that the foundation raises funds for the Police Department so Moore and other LAPD leaders don’t have to and that it never relies on them to solicit money on its behalf.

“If you carry a badge and a gun, you shouldn’t be asking for money,” she said.

Moore noted the same “bright line,” saying he and other LAPD commanders “provide information” to foundation donors, including about financial hurdles the department is facing, but never solicit money directly.

“Our ethics are unbending,” Moore said. “We do not go and ask people for money.”

But LAPD and foundation records obtained by The Times show Moore and Katz working in tandem to raise private funds for the department. They also reveal a robust and successful operation, led by some of L.A.’s wealthiest residents and biggest names, to raise private and often anonymous funding for the largest police agency in the western United States.

It’s a powerful — yet far less public — counterpoint to the local defund movement.

How it works

The Los Angeles Police Foundation was launched in 1998 at the urging of then-Chief Bernard Parks and his wife, who helped it get off the ground by modeling it after organizations in New York and New Orleans.

LAPD: New foundation will help pay for projects when no city resources are available.

It has been embraced by every LAPD chief since and, to date, has donated more than $45 million to the department, according to its 2021 tax forms.

The foundation’s donations represent a small portion of the LAPD’s annual budget of more than $3 billion, of which more than 95% goes toward salaries and other personnel costs. But they represent a larger percentage of LAPD spending on advanced training, technology and equipment.

All donations from the foundation to the LAPD must be approved publicly by the Los Angeles Police Commission, and every donation exceeding $17,906 must also go before the City Council. But the people, corporations and nonprofits providing the underlying funding are rarely disclosed during that process.

The commission and council routinely rubber-stamp donations without providing a public accounting of who is behind them, and the foundation has consistently refused to release its donor list.

The proposal for more LAPD funding could easily become an issue in the June 7 primary election, which features several candidates who want to rein in law enforcement costs.

In 2019, Katz denied a Times request for all donors who had given $1,000 or more and declined to say whether any had earmarked their donations for particular causes. She cited the foundation’s “obligation to protect and respect” its donors’ privacy.

The foundation again denied a Times request for a list of donors in August 2021. That same month, The Times filed a public records request with the LAPD for years of emails between Katz and police officials, which turned up more than 7,200 pages.

The first set of records, released to The Times in October 2022, not only revealed private conversations between police and foundation officials but included financial filings, fundraising strategies and incomplete lists of donors and their past contributions or pledges.

Some of the biggest givers include Steve Ballmer, the former Microsoft chief executive and owner of the Clippers, and Tony Pritzker, scion of the prominent Pritzker family, whose interests include Hyatt Hotels Corp. Other major donors include Jeffrey Katzenberg, the DreamWorks co-founder and Hollywood producer, and Casey Wasserman (grandson of the late movie mogul Lew Wasserman), another entertainment executive who is president of the Wasserman Foundation and chair of the organizing committee for the 2028 Summer Olympics in L.A.

A representative of Ballmer’s philanthropic organization, the Ballmer Group, said it has funded projects aimed at improving public safety, including Community Safety Partnership teams, which prioritize collaboration between LAPD officers and community members in neighborhoods hit by violence. (The Ballmer Group also is helping fund the Los Angeles Times’ new early childhood education initiative, a two-year program for which The Times’ newsroom retains complete editorial control.)

A spokeswoman for Pritzker said he had no comment on his donations. Neither Katzenberg nor Wasserman responded to requests for comment.

The emails also show efforts to solicit support from wealthy Angelenos.

In February 2020, Katz wrote an email to Moore with the names and contact information of more than a dozen people whom a consulting firm working for the foundation had determined Moore should call directly — “to introduce yourself and ask if you can meet with them to talk about the state of the Department and your vision/goals.”

At the top of the list, which Katz said was “in order of priority,” was Wallis Annenberg, president and chief executive of the Annenberg Foundation. Second was Walter Wang, chairman and CEO of JM Eagle Inc., the world’s largest manufacturer of plastic pipe. According to 2021 tax records, both serve on the foundation’s board.

Next on the list were Rick Caruso, the developer and former police commissioner who just spent more than $100 million of his own money on a failed attempt to become L.A.’s mayor, and his wife, Tina. There too were Jeanie Buss, controlling owner and president of the Lakers, and Lakers legend Magic Johnson and his wife, Cookie.

Ted Sarandos, the CEO of Netflix, and his wife, Nicole Avant, were also listed. Avant — daughter of music mogul Clarence Avant, known as the “Black Godfather,” and philanthropist Jacqueline, who was murdered in 2021 — is an investor and was U.S. ambassador to the Bahamas in the Obama administration.

None responded to requests for comment, and it is unclear whether Moore followed through on calling them or if they donated to the foundation as a result.

Moore and Katz said not every potential meeting they discussed by email took place.

The effects on policing

The foundation has had a major impact on the LAPD over the years — in many cases championing progressive causes that reflect the politics of its biggest donors and helping to keep the department at the forefront of policing trends.

For example, the foundation in 2008 stepped in with more than $1.4 million in private funding to help clear a backlog of thousands of untested rape kits that the LAPD had kept in storage freezers for years.

In 2015, it provided nearly $2 million for the LAPD to purchase its first officer body cameras, advancing a program, now publicly funded, that provides greater transparency around police actions, including shootings. It has spent nearly $1.6 million in recent years to bankroll the Community Safety Partnership program.

In 2020, the foundation spent $350,000 to fund an outside review of the LAPD’s handling of mass protests following the murder of George Floyd and another $350,000 to hire a marketing firm to help the department improve its recruitment of female, Black and Asian and Pacific Islander officers. It also spent about $600,000 replacing the LAPD’s downtown Memorial for Fallen Officers.

In 2021, the foundation donated nearly $1.6 million for a virtual-reality training system with which officers can practice de-escalation and other alternatives to using force. Last year, the foundation donated $1 million to begin rolling out Active Bystandership for Law Enforcement training, which teaches officers to intervene when they witness their peers using excessive force.

The foundation says it has a policy against funding basic training, salaries, police vehicles, weapons or ammunition. Between major projects and campaigns, it funds smaller events aimed at boosting officer morale, such as holiday parties, and equipment purchases for individual units, such as binders to help homicide detectives keep case files organized.

The foundation also funds big-ticket technology and equipment purchases that the city is unwilling or unable to make.

In November, activists objected to a donation of nearly $278,000 for a robot that can open doors, climb stairs and help flush suspects from homes. Officials said the robot would be deployed to assist the department’s SWAT team in carrying out high-risk search warrants and apprehending barricaded suspects; activists said it was military equipment that has no place in city policing.

The foundation has also helped the LAPD purchase drones, closed-circuit cameras and data analytics software that officials say are used ethically and sparingly but activists say are wildly intrusive and used disproportionately in communities of color.

Hamid Khan, a regular critic of the LAPD and a coordinator with the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition, said the foundation over the years has helped the department build a dystopian network of surveillance capabilities by paying for equipment purchases that would have raised more questions had they been publicly funded.

Khan cited as one example the LAPD’s purchase years ago of Palantir data analytics software, for which the foundation contributed $178,000 in funding from Target Corp., Katz said. The software was used as part of a “predictive policing” program that attempted to identify “chronic offenders” and crime hot spots for increased attention from law enforcement. But it was discontinued amid concerns that it lacked oversight, used inconsistent criteria to label alleged or potential offenders and unfairly targeted Black and Latino communities.

The Los Angeles Police Department has scrapped a second data policing program it once hailed as a way to target violent offenders in neighborhood hot spots, following concerns that the programs unfairly target black and Latino communities.

Target has since stopped donating to the foundation.

Khan said donations to the LAPD from private individuals and corporations at the very least give the appearance of impropriety — suggesting that deep-pocketed interests can buy favor with law enforcement or help set the approach to policing.

“We have to be really looking at it in a very critical way,” he said.

Kandyce Fernandez, an assistant professor of public administration at the University of Texas at San Antonio who has studied private funding of police departments, said L.A. is no outlier.

She and a research colleague recently counted more than 250 similar foundations nationwide, she said. The number surged starting in 2010, when many cash-strapped cities were looking for lifelines amid the Great Recession.

However, the Los Angeles Police Foundation is one of the biggest such groups in the country. And it is by far the largest private donor to the LAPD, according to a 2020 audit by the department’s inspector general, providing $6.6 million of the $9.4 million in total donations the LAPD received in 2019.

Los Angeles police officials promised improvements to the LAPD’s process for accepting donations after two audits identified issues with documenting and tracking such gifts.

Such funding, Fernandez said, raises questions about equity, when richer areas attract more funding, and about transparency, when the people, corporations or nonprofits behind the donations aren’t disclosed.

Big business and other benefactors

Emails between the LAPD and foundation officials show that in addition to individual philanthropists, the foundation has received funding from companies that have interests in the city and do business directly with the department — at times with its help.

For example, in May 2019, Katz wrote an email to Moore’s chief of staff, then-Department Chief Robert Green, saying she was “working on securing sponsorships” for the foundation’s annual “Above and Beyond” fundraiser, which honors officers for bravery in the field.

“Is it possible for the Department to put together a list of its top 10-15 vendors (with contact names and email addresses, if available) for me to reach out to?” Katz asked.

“Happy to provide them,” Green replied.

Four months later, the event’s main sponsor was Motorola Solutions, which does substantial business with the LAPD and has held a master service agreement for telecommunications work with the department since 2014. That contract was renewed in February for nearly $9.5 million.

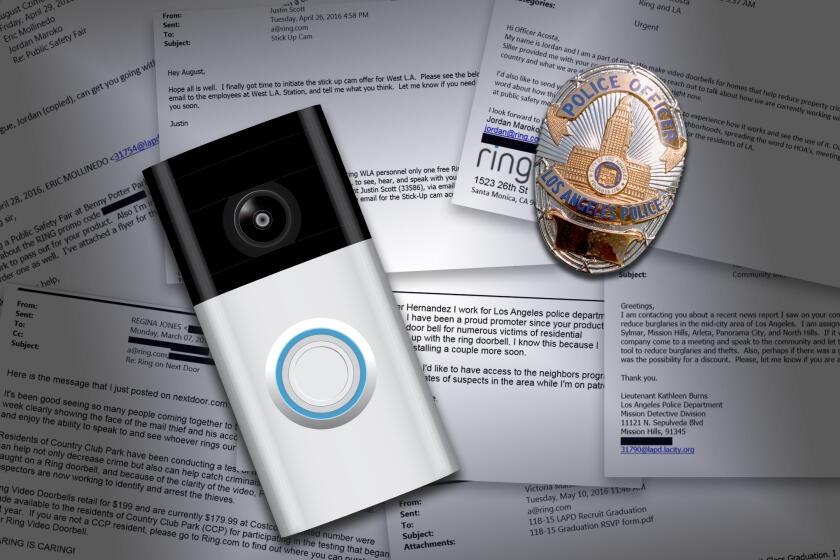

Other event sponsors included Axon, maker of the LAPD’s body cameras and other technology; Glock Inc., which has sold pistols to the department; and Ring, the Amazon-controlled manufacturer of security cameras that once tapped LAPD officers to hawk its products to residents.

Ring provided at least 100 LAPD officers with free devices or discounts and encouraged them to endorse and recommend its doorbell and security cameras to police and members of the public.

The Times found no evidence that the donations influenced contract decisions.

Neither Motorola nor Glock responded to requests for comment. Axon, in a statement, said it sees supporting the Los Angeles Police Foundation as a means of supporting “the broader community” and is “committed to doing business transparently” but declined to tell The Times how much it has donated.

Ring, which donated $10,000 to the 2019 “Above and Beyond” event, no longer works with the LAPD to sell its products and said in a statement that it has stopped donating to law enforcement organizations.

Some of the foundation’s biggest donors are other foundations and nonprofits.

The Ballmer Group has been a major funder of body cameras and the Community Safety Partnership program. In just one example, it gave $250,000 in 2020 for a CSP site in the South Park neighborhood.

The Ahmanson Foundation, a major philanthropic body founded in the 1950s in L.A. County by financier Howard Ahmanson and his wife, Dorothy, has donated many times — including a $5-million contribution toward a recent foundation campaign to replace aging LAPD technology systems.

Bill Ahmanson, the group’s president, said it assesses requests for funding from the Los Angeles Police Foundation just as it does requests from any other potential beneficiary — by looking at the population that will be served and whether the contribution will be meaningful.

Ahmanson said he sees no problem with police officials like Moore working to attract private funding.

“Everybody in this city is trying to raise funds,” Ahmanson said. “We always seem to have enough money in the city to do everything we want but never enough money to do anything well.”

‘I need you to step up’

According to the LAPD and foundation emails obtained by The Times, the foundation has frequently leaned on Moore to meet with major donors and business leaders and lay out the ways in which the department could benefit from private cash.

Despite their claims to the contrary, foundation officials have repeatedly prodded Moore to ask for money directly, and he has skirted that line — if not crossed it.

For example, in April 2020, the foundation was in the midst of a major fundraising campaign to upgrade the LAPD’s outdated technology and computer systems. It was also trying to get a handle on the department’s needs related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

On April 15, Katz sent Moore a planning memo for a private phone call between him and more than 40 billionaires, millionaires and corporate and nonprofit representatives from the worlds of development, sports, merchandising, private equity, banking, healthcare and entertainment. The memo had been drafted by the consulting firm Gonring Lin Spahn, which the foundation was paying $25,000 a month to help run its tech campaign.

Also on the list was developer Steve Soboroff, who has been criticized by activists for helping to orchestrate donations to the foundation while serving on the Los Angeles Police Commission, of which he is a current member. He also has been pilloried for directing funding to the foundation personally as a former board member of the Weingart Foundation.

Soboroff said in an interview that all of his support has been aboveboard, and he has never been sanctioned for violating city ethics rules.

In addition to the attendee list, the memo provided “suggested talking points” for Wasserman, Katzenberg and Pritzker, the technology campaign’s co-chairs, as well as for Moore — advising him to express his desire for more officers on the streets and stress the department’s growing financial needs amid the pandemic.

“My budget will likely be cut, which means we need to be thinking about the long term now,” read one of the talking points for the chief. “If you want to step up, I need you to step up for this,” read a second.

Months prior, Katz had sent Moore talking points for a planned one-on-one call with Peter Guber, chairman and chief executive of Mandalay Entertainment and co-owner of the Dodgers and Golden State Warriors. That memo proposed that Moore ask Guber to donate $1 million and join Wasserman, Katzenberg and Pritzker as a technology campaign co-chair.

“Right now, all the Co-Chairs of the Capital Campaign have committed $1 million,” one of the talking points for Moore read. “I know all of us couldn’t imagine leading this effort without you.”

Guber did not respond to a request for comment.

In interviews with The Times, Moore stood by his claim that he has never solicited money for the foundation. He said he has appreciated the “talking points” from foundation leaders but never followed them when they crossed his “bright-line standards” against soliciting funds.

Moore has given the foundation permission to raise funding by granting naming rights to an LAPD facility and provided guidance on opposing any cuts to public funding.

At one point in 2020, Katz emailed Moore about selling naming rights to public LAPD facilities — in part because Pritzker wanted to give $1 million to put his name where rank-and-file officers would be sure to see it.

“I spoke with Tony Pritzker’s foundation head, and his primary priority is visibility with the officers,” Katz wrote. “In looking at the opportunities for $1M gifts, I thought that one of the [Elysian Park] ranges would be best, but I would welcome your thoughts/opinion.”

“This is fine,” Moore wrote back. “I support.”

Today, LAPD officers receive combat training at the Pritzker Combat Range.

Judy Schroffel, Pritzker’s senior executive assistant, said Pritzker had no comment on the deal.

Later that year, the LAPD — like every other city department — was facing potential budget cuts due to massive revenue shortfalls related to COVID-19.

Again, the foundation got to work, the records show, discussing with Moore an organized campaign to get business leaders to reach out to city officials — including then-Mayor Eric Garcetti and members of the City Council — to oppose cuts to police.

On Dec. 9, 2020, Katz emailed Moore a list of business leaders with the Valley Industry & Commerce Assn. who were meant to be on a call with him to hear about the effects of budget cuts on public safety in the San Fernando Valley.

“I am sure they will have questions and are looking for a call to action, which I’ve told them will be primarily to contact the city councilmembers and mayor to urge them not to adopt the cuts,” Katz wrote.

“Thank you!” Moore wrote back. “Good group.”

Stuart Waldman, the group’s president, said he had requested the meeting because group members were “really concerned” about police budget cuts. During the meeting, he said members “expressed overwhelming support” for the LAPD and urged him to “put out an action alert” to other members, which he did.

About a week later, on Dec. 18, Dwayne Gathers of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce wrote to Katz, saying he and other board members were “ready to engage” in opposing LAPD cuts, including by getting chamber businesses and their employees to voice opposition.

Katz forwarded the note to Moore, who responded, “Thanks!! Sounds like progress.” He then suggested that a written campaign — in the form of letters to the editor or opinion editorials in local news outlets — could be helpful.

Moore said naming the combat range after Pritzker was a “tribute” to his generosity to the department. He said he has always been candid with local business leaders about the needs of the department and at times encouraged them to make their voices heard by speaking with their elected representatives.

The future of giving

LAPD officials for years have been defending the agency against critics of private funding.

Following its audit of donations in 2020, the LAPD inspector general’s office recommended that the department improve its tracking and documentation of donations, improve its process for assessing whether donations raise conflicts of interest and “set forth appropriate parameters limiting special access for donors to Department personnel and/or facilities.”

The audit had found, among other issues, that despite an LAPD policy barring donors from receiving preferential treatment, half a dozen foundations raising private funding promised just that — telling donors that “a certain level of donation would ensure a meeting” with LAPD commanders or that small contributions could get them “tours of Area stations or some other sort of unique Department access or experience.”

The audit did not specify whether the Los Angeles Police Foundation was among those promising special access, though the records obtained by The Times show that it was providing donors with such access through its exclusive meetings with Moore.

Recommendations aside, the inspector general concluded that the LAPD’s overall process for receiving donations was “generally well designed.”

In a recent interview, William Briggs, an attorney and president of the Los Angeles Police Commission, said the foundation is doing good work in L.A., citing as an example the recent $1-million donation for active bystander training — which he said will “change the culture of the LAPD” for the better.

“If the city could fully fund the LAPD, there is no doubt that it would. But until such time as this can happen, the foundation assists with maintaining the LAPD at the level of a world-class police department,” Briggs said. “I am grateful for their commitment.”

Soboroff — who has long helped the foundation raise funds, most recently for a program to offset housing costs for new officers — said any criticism of the group is misplaced.

He said no one who donates or is otherwise involved with the foundation “receives or asks for favors,” and he has never seen anything untoward occur — from either its leaders or police commanders — over decades of observing its work.

Soboroff said it would make sense for companies that have contracts with the city or the LAPD to publicly disclose contributions to the foundation as a matter of transparency, even though he said such contributions have no impact on contract decisions and should be allowed to continue.

But, he said, he understands why some private donors want to remain anonymous — and supports their ability to do so — given the atmosphere around policing. He said he has received death threats from activists for his work on the commission — which is exactly what donors fear.

“You want to look at my emails? You want to see the security I have?” Soboroff said. “I don’t blame them one bit.”

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.