Once again we have entered the time of the winter solstice — when daylight is scarce and the creeping darkness seems to whisper: Slow down. Turn inward. Fortify yourself against the long, cold night ahead.

Although shrouded in myths, the winter solstice is a physical event that occurs this year on Dec. 21. It is the day when the North Pole reaches its farthest tilt away from the sun, resulting in the shortest period of daylight of the year in the Northern Hemisphere, followed by the longest night. It is also the day when the sun reaches its lowest maximum point in the sky. In Los Angeles the sun will rise at 6:55 a.m. and set at 4:47 p.m.

On the other side of the world, the Southern Hemisphere experiences its summer solstice on the same day, a sage reminder that on this planet at least, the time of greatest darkness is also the time of greatest light.

“The winter is the summer, the summer is the winter — these things exist at the same time and are not exclusionary,” said Maja D’Aoust, a writer, artist and metaphysical practitioner who goes by the name Witch of the Dawn.

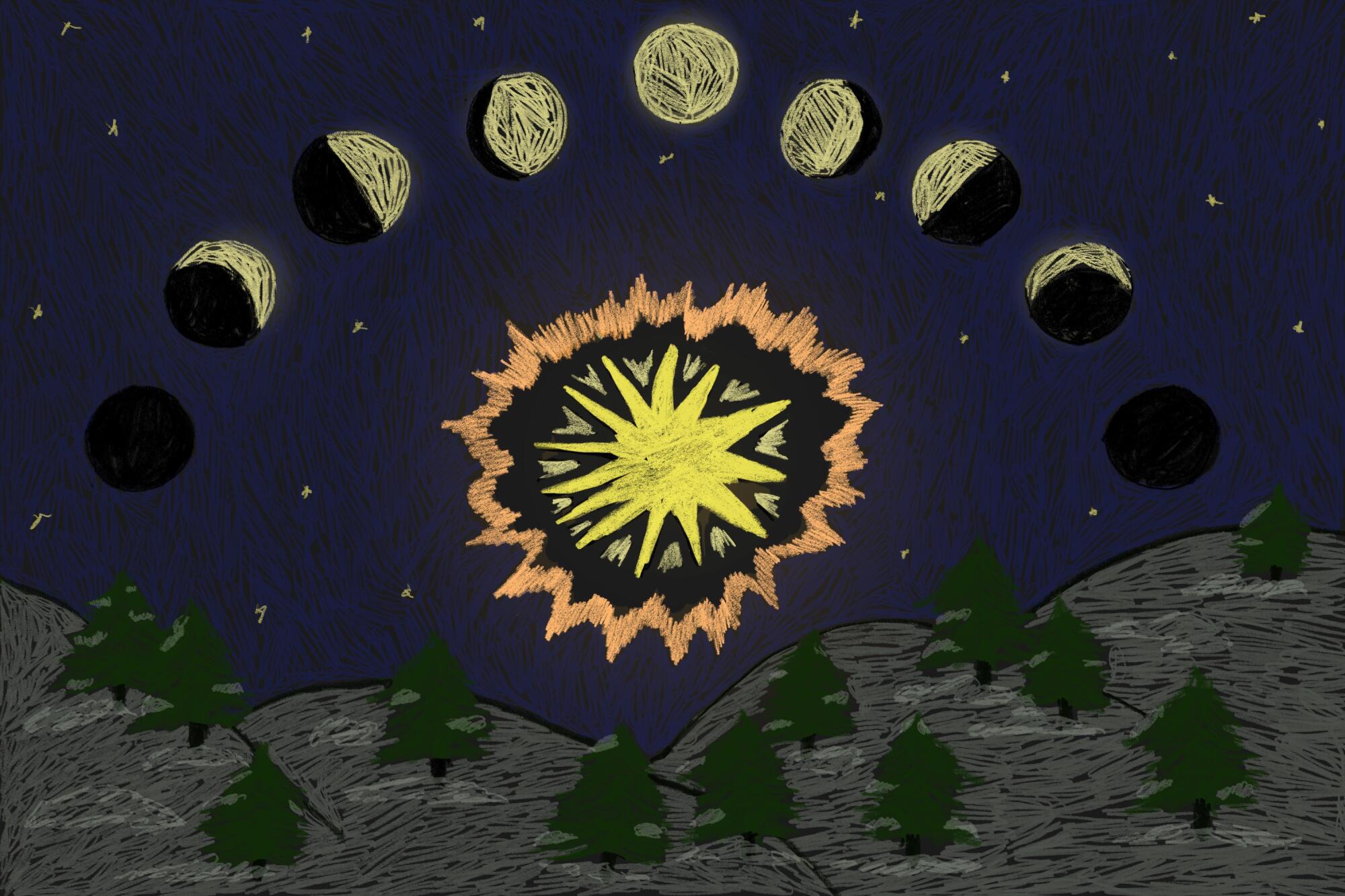

Throughout the ages, the winter solstice has been understood as a cosmic turning point. To witness the rising sun after the longest night of the year is a potent symbol of hope across cultures that light has once again triumphed over darkness.

The seasonal cycles of the Earth are experienced universally by all humanity; generation after generation, they shape how we make sense of the world and our place in it, said John Grim, co-director of the Forum on Religion and Ecology at Yale University. “Native people speak of the world speaking to them,” he said. “If we situate the human in the context of our long evolutionary history, then the world has been speaking to us for a very long time.”

Embedded in the physical machinations of the solstice, our ancestors saw stories and myths that continue to inform us today. Some cultures understand the darkest time of year to be a period of regeneration and renewal for themselves and the planet — a time to pray for rain and snow and a good harvest. For others, the solstice is a time of fear and worry about the dark energies and spirits that are believed to thrive in the long night.

Another pervasive theme of the winter solstice is divine birth. The Egyptian sun god Horus, the Greek sun god Apollo and the Indo-Iranian sun god Mithra were all believed to have been born into the darkness of the winter solstice, their births portending the return of the light. Some scholars argue that it is no coincidence that the birth of Jesus, who called himself “the light of the world,” is celebrated around this time as well.

Southern California, one of the most spiritually diverse places on Earth, is home to a wide variety of contemporary solstice practices, including the Kakunupmawa ceremony celebrated by the Santa Ynez Chumash tribe, the Korean holiday Dongji and Shab-e Yalda, celebrated by the Iranian diaspora.

One can also make the case that the Jewish celebration of Hanukkah can be interpreted as a solstice holiday, as can the secular American observance from late November to December that we’ve come to call “the holidays.”

Here, we explore five solstice practices that continue today, but keep in mind: regardless of how you honor this dark time of year — whether engaging in gift-giving , lighting up the dark with string lights or partying on New Year’s Eve — we are all engaging with the rhythms of the Earth.

Chumash Solstice Festival

The winter solstice is celebrated by the Santa Ynez Chumash tribe each year with the multiday Kakunupmawa ceremony. It is a time for bringing people together, praying for the winter rains, honoring those who have passed on in the last year, forgiving debts and grievances and ensuring the return of Old Man Sun.

“It’s our main ceremony because it carries so much weight,” said Nakia Zavalla, cultural director and tribal historic preservation officer for the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians. “That’s what our ancestors taught us.”

In the Chumash tradition, Old Man Sun carries a torch as he makes his way across the sky and the winter solstice marks the start of his annual journey. Humans and nature are engaged in a sacred partnership, and each has a role to play to ensure the return of the light essential to all life. “It’s our ancient way of life that was passed down by the ancestors,” Zavalla said. “These things had to happen every year.”

For the past eight years Zavalla and other members of the tribe have organized a formal solstice ceremony on the Santa Ynez reservation’s ceremonial grounds. There is singing, dancing, praying, and coming together as a community to feast. The day also includes a hike up to the sacred mountain Owotoponu, also called Grass Mountain, in the Los Padres National Forest to honor those who have passed on.

Zavalla and other cultural bearers are wary of revealing details of exactly what occurs in the Santa Ynez Chumash solstice ceremony, and she herself is still uncovering what it entails, with guidance from the ancestors.

“Unfortunately, the effects of colonization mean we are still bringing back our customs, so a lot of this is reconnecting to something that was a way of life,” she said. “But the more we do through our ceremonies, the more of a connection we feel — whether it’s to the elements of the Earth, the seasons or knowing the purpose of everything in its place.”

Shab-e Yalda

The winter solstice celebration Shab-e Yalda has its roots in ancient Iran, when local clans worshiped the sun god Mithra. According to myth, Mithra was born on the shortest day and longest night of the year and the holiday represents the triumph of light over darkness.

Shab-e Yalda continues to be celebrated today in the Iranian diaspora with family gatherings, the consumption of special foods like pomegranate and watermelon, prophetic poetry readings and staying up all night to watch the sunrise.

“After the longest and coldest night of the year, the sunrise is a reminder of hope,” said the Iranian epic storyteller Gordafarid, who lives in Los Angeles. “Hope for the end of darkness, hope for the sun, hope for a better and brighter tomorrow.”

Pomegranates are one of the primary symbols of the holiday. They are red — the color of Mithra and the color of the sky in the moments before the sun rises. And their seeds, which are likened to rubies, are believed to be regenerative — a symbol of fertility, Gordafarid said.

Contemporary celebrations often occur in the homes of family elders, said Alireza Ardekani, executive director of the Farhang Foundation, which promotes Iranian art and culture. People eat soups and stews and read aloud poems by the 14th-century poet Hafez.

“What you basically do is a fortune telling,” Ardekani said. “You randomly open to a page and what the poem says is a foreshadowing of what is coming in the year.”

Shab-e Yalda celebrations have grown more popular in recent years in defiance of the Islamic Republic, which doesn’t promote or honor them.

“It makes people want to celebrate them even more as a way to preserve the culture and the heritage,” Ardekani said. “This is a way of being reminded of who you are and where you come from.”

Dongji

The winter solstice is celebrated in a variety of ways across much of Asia. In Korea, the holiday is called Dongji and is honored by eating a special type of red bean porridge, patjuk, with dumpling-like balls made from rice flour that are thought to resemble bird’s eggs — a symbol of new beginnings.

Patjuk can be sweet or savory. The reason to eat it at this time of year is to balance out the yin energy of the longest night of the year with the yang energy of the red bean porridge, said Kwang Uh, owner and chef of the Korean restaurant Shiku in Grand Central Market. “Red is the color of yang energy, and so when you consume the red bean soup you are also consuming that energy. That’s the theory,” he said.

Because the winter solstice is the longest night of the year, it is the time of the highest peak of yin energy, he said.

Red beans are also believed to prevent disease and protect against the evil spirits that prevail in the winter time, said Gloria Kim, who manages the Koreatown Senior and Community Center. “Dongji is the most powerful day of negative energy,” she said. “The red color of the bean protects against the negative energy.”

People used to gather for Dongji — and they still do at the Koreatown Senior Center — but Uh and his wife and business partner, Mina Park, said those celebrations are happening less and less, both in Korea and among Korean Americans in the United States.

“Younger people may not even have the patjuk,” Park said. “I think these days it’s more like your mother might call you and ask if you had patjuk today.”

Hanukkah

Each year, normally in December but sometimes beginning in late November, Jewish people around the world celebrate Hanukkah by lighting the menorah, adding one candle each night for eight days. The celebration is usually accompanied by songs, games, foods fried in oil and gifts.

The timing of Jewish holidays are dictated by a lunar calendar, so the Hanukkah celebration does not always occur on the precise night of the solstice. Still, some rabbis see parallels to the holiday and solstice celebrations taking place around the same time.

“The way I see it, we are imitating the sun at the time of the solstice,” said Rabbi Jill Hammer, co-founder of the Kohenet Hebrew Priestess Institute, who is based in New York. “Every night there’s a little more light.”

She added that unlike most Jewish holidays, which start on the full moon, Hanukkah begins on the waning moon and continues through the dark moon. “It’s a holiday of dark nights,” she said.

Hanukkah was originally celebrated to honor the military victory of a small band of Jewish fighters over the much larger Syrian army, but contemporary practices focus more on the miraculous story, added later, about a lamp in the holy temple that had only enough oil for one night, yet lasted for eight nights, until more oil could be procured.

To commemorate this miracle, the rabbis instituted the lighting of the menorah, increasing the amount of light each night.

“It’s poetic and beautiful, especially in winter, when we need the light to increase,” said Rabbi Susan Goldberg, founder of the Jewish spiritual community Nefesh on the east side of Los Angeles.

The rabbis also directed Jews to place their menorahs in the windows of their homes, so they could be seen from the street. “We’re supposed to share the light,” Goldberg said. “We are offering light to each other.”

“The Holidays”

Candy canes. Office lobbies with giant trees twinkling. Hallmark Christmas movies on TV. These are our 21st-century markers that we are entering the time of the winter solstice.

“The yearly cycle is now reflected in the iconography of American capitalism,” said Sabina Magliocco, chair of the religion department at the University of British Columbia. “If you go to Walgreens you know what time of year it is.”

That may sound like a sad state of affairs, but solstices and equinoxes have always been connected to the economy, Magliocco said. In the earliest societies they helped people know when to hunt, plant and harvest. It’s not so different today, when business owners depend on the holiday shopping season to boost sales at the end of the fiscal year.

While shopping is a dominant theme of the contemporary secular holiday season, there are others as well — specifically, light. When people string holiday lights around their yards, light candles in their homes or illuminate the Christmas tree, they are engaging in homeopathic magic, Magliocco said. This is a type of magic where like controls like.

“If we want something to happen then we have to do something materially to make it happen,” she said.

One way to see our collective urge to light up the darkness around the winter solstice is that we are communicating to the universe that we want and need the sun to return.

It’s a practice that would be familiar to many of our ancestors as well.

Happy solstice!

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.