Cal State University poised to drop plan for tougher math admissions requirement

California State University trustees are poised to abandon a proposal to require a fourth year of math-related coursework for admission, ending a plan introduced six years ago that touched off fierce criticism among many who said it would create barriers for students trying to enter the system.

Administrators are recommending the board of trustees reject the proposed requirement in January, citing new research showing that nearly all CSU applicants and enrollees already take four years of math. They also raised concerns that the new requirement would hurt students whose high schools are underresourced or still struggling with the effects of the pandemic on education.

“The CSU does not plan to pursue a change to our admissions requirements,” said Nathan Evans, the system’s associate vice chancellor of academic and student affairs during a Nov. 15 meeting.

During a discussion about the recommendation, several trustees on the 23-member board indicated they endorsed ditching the proposed requirement but vowed to continue to find ways to help develop students’ quantitative reasoning skills once they arrive on campus.

First introduced in 2016, the proposal called for students to take an additional year of math, science or other quantitative reasoning coursework such as computer science or personal finance to qualify for admission into the country’s largest four-year system of public higher education.

The plan was enthusiastically supported by then-Cal State Chancellor Timothy P. White as a way to increase rigor and boost college graduation rates, close achievement equity gaps and better prepare students for the workforce.

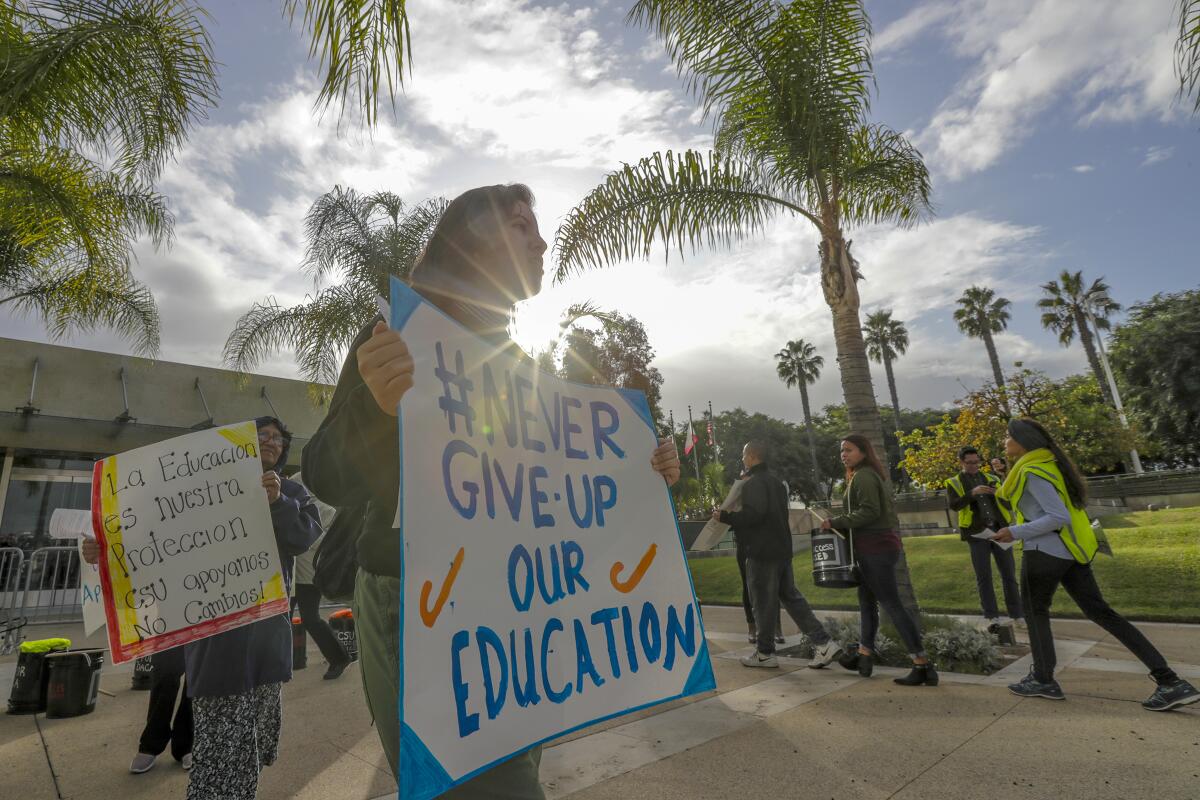

But dozens of social justice groups, education advocates, school districts and lawmakers from across the state campaigned against the proposal. They argued that it would unfairly prevent Black and Latino students, and those from low-income families, from enrolling in the system because of disparities in access to such classes and the lack of qualified teachers.

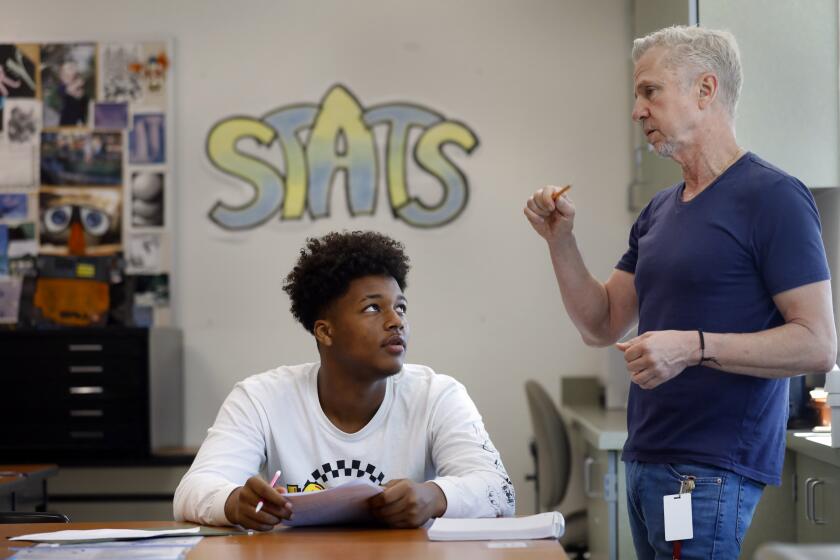

The CSU is weighing requiring an additional year of math, science or other quantitative coursework for admission.

Christopher Nellum, executive director of Ed Trust-West, a nonprofit organization focused on education equity, said at the time that the system did not conduct enough research or provide data on how an additional requirement would affect students.

“Just by virtue of their ZIP Code, or where they live, or their ability to access a school with the right resources, they may have been shut out of CSU,” Nellum said of students. “We wanted the CSU to provide evidence that wasn’t going to happen or, if it was going to happen, they had a plan for minimizing impact.”

Cal State officials commissioned a study in 2020 with the research firm MDRC to measure how the additional requirement would affect students.

The study showed that 94% of California high school graduates who meet current admission requirements for the state’s public universities were also already taking a fourth year of math-related coursework.

“The vast majority of California high school graduates that may aspire to attend a CSU are already taking and passing an additional quantitative reasoning course, even though it is not currently required,” said Susan Sepanik, a senior associate with MDRC.

Researchers found students who met the proposed requirement were more likely to pass their first college-level math course than their peers who did not take a fourth-year math, science or quantitative reasoning course.

But interviews with school district leaders surfaced concerns not all high schools would be able to provide additional classes for students to meet the proposed requirement. Schools in rural and low-income communities said they would struggle to provide extra instruction because they do not have enough teachers.

Cal State administrators said that if trustees abandon the proposed requirement, they will instead strongly recommend that students take four years of math-related coursework.

The system will also focus on providing extra academic support to first-year college students. To help address statewide teacher shortages, the system said it has dedicated more resources to prepare pre-kindergarten through 12th-grade teachers in math, science and computer science instruction.

“Any future admissions proposal should not punish students for attending a high school in the quote-unquote wrong school district, a district that maybe isn’t giving them what they need,” Nellum said. “It’s a major win.”

Community college enrollment is at its lowest level in 30 years as educators scramble to meet the needs of a new generation of students who may be questioning the value of higher education.

He said the fact that so many Cal State applicants are already taking a fourth-year math-related course indicates that the proposal would not have addressed the issue of improving graduation rates and closing gaps in academic outcomes.

If students “are already fulfilling a requirement coming into your system and you’re still not seeing the sorts of outcomes that you would like, that points to changes that your system should make,” he said. “This isn’t about the course. It’s about ... what programs, what services, what supports you are offering.”

Maria Linares, a student trustee who spoke against the proposal before becoming a board member in 2021, said she was relieved that administrators have urged trustees to reverse course.

“I’m really happy to see that we have taken a complete turn,” said Linares, a voting member of the board. “I remember getting teary-eyed and crying, just thinking how many students we would have to turn away, or that we would be setting up barriers for, if this proposal ever came back to the table and we adopted it.”

Other trustees said the university system must still work on equipping students with the quantitative reasoning skills they need to graduate from college.

“I know that when we raise the bar of expectation, students meet that higher and bar. And yet we want to be so mindful of equity and access,” said Diego Arambula, a trustee. “I do not see that as us walking away from this as a priority.”

Another trustee, Leslie Gilbert-Lurie, said the issue boils down to making sure students are prepared for where they land after college.

“The journey is not just to get to the CSU,” Gilbert-Lurie said. “It’s not yes or no, two classes or one, it’s how do we get more students into the tent and make sure that they have the most knowledge they need to be their most successful in life.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.