The summer before 14-year-old Alexander Neville would have entered high school, he sat both of his parents down at the kitchen table in their Aliso Viejo home and told them he’d been taking Oxycontin pills he bought on Snapchat.

He had self-medicated with pot in the past, but this was different.

“It has a hold on me, and I don’t know why,” he told them in 2020.

Alexander’s mother, Amy Neville, said they called a treatment program the next day and were waiting to hear back on rehab facilities. Alexander got a haircut, went to lunch with his dad and said goodnight to his parents before going up to his bedroom at the end of the day.

The following morning, Neville went to wake Alexander for his orthodontist appointment. She found him unresponsive. His skin was blue, and he wasn’t breathing. After his parents called 911, Alexander was taken to a hospital, where he was pronounced dead at 9:59 a.m. on June 23. The drug treatment facility called the Nevilles four minutes later.

Later that day, a narcotics task force arrived at the Neville family home and told them Alexander’s death could’ve resulted from fentanyl, not Oxycontin.

“We didn’t understand — how did Alexander take so much Oxy that he died? It didn’t make sense,” Neville said. “The fact that he could die from a prescription pill was not on our radar, but these are counterfeits and fakes, and we had no idea.”

Neville said they found out her son died from a single counterfeit pill containing fentanyl — a tragedy that has been rising in recent years.

Drug use among teens ages 14 to 18 remained relatively stable between 2010 and 2020, according to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About 30.2% of 10th-graders in 2010 said they had used illicit drugs in the past year, according to a Journal of the American Medical Assn. research letter published in April 2022. Ten years later, that number was nearly identical, at 30.4%.

Yet more young people are dying from fentanyl than ever before. Teen fentanyl deaths more than doubled, from 253 in 2019 to 680 in 2020, the report showed. Last year, the number jumped to 884. And fentanyl was the cause of 77.14% of drug deaths among teenagers last year.

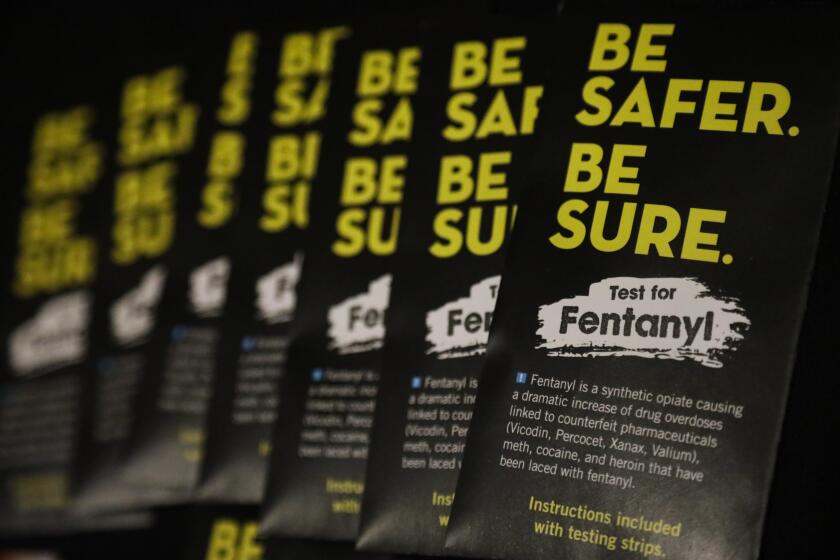

Fentanyl is often mixed with other drugs (including heroin, methamphetamine and cocaine) to increase potency, but it can be deadly. Test kits can help.

The dramatic shift can be attributed to lethal doses of fentanyl — a substance 100 times stronger than morphine and 50 times stronger than heroin — being increasingly disguised as prescription pills or added to other drugs, according to public health and law enforcement experts. Social media also have made drug dealers more accessible to young people, who might be seeking prescription medication to lessen their anxiety or deal with other mental health struggles.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration has warned about the existence of brightly colored, “rainbow” fentanyl pills, made to look like candy, that also could be used to target young people. Rainbow fentanyl was first reported in February and has been seized in nearly two dozen states, according to the DEA.

In 2020, the Los Angeles Police Department’s Gang and Narcotics Division seized about 117,000 fentanyl pills, Det. Art Stone said. That number ballooned to 858,000 pills in 2021. So far this year, nearly 3 million fentanyl pills have been seized, Stone said.

“The moral of the story is that fentanyl trafficking has upped significantly,” he said.

Seizures of counterfeit pills containing the deadly synthetic opioid fentanyl have more than quadrupled so far in 2022, compared to the same period last year, according to police officials.

In 2016, while the country was still deep in the throes of the opioid epidemic, law enforcement was just learning about fentanyl trafficking, according to Stone. Recent regulations have been effective at targeting the overprescription of medication, he said, but they also reduced the number of pills being diverted to the streets. That gave rise to fentanyl trafficking, in which the drug is being funneled from Mexico through California and other border states to the rest of the U.S., disguised as other medications and being peddled as legitimate pills.

“Whether they’re willing users or someone who thinks they’re taking a Percocet pill, it really doesn’t matter,” Stone said. “The end product is gonna be fentanyl. If you buy it on the street, it’s gonna be fentanyl.”

Dr. Wilson Compton, deputy director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, said that while national rates of opioid misuse have decreased over the years, overdose deaths have increased because the products are becoming more poisonous. In addition to prescription opioids, fentanyl is being disguised as Ritalin, Adderall, Xanax and other pills, Compton said.

“The idea of teenagers taking risks and using substances is not a new problem,” he said. “But what has changed is the lethality and the danger of the substances that they’re ingesting. And unfortunately, simply telling teenagers that a substance is dangerous has not always been a successful way to communicate and help people make changes in their behavior.”

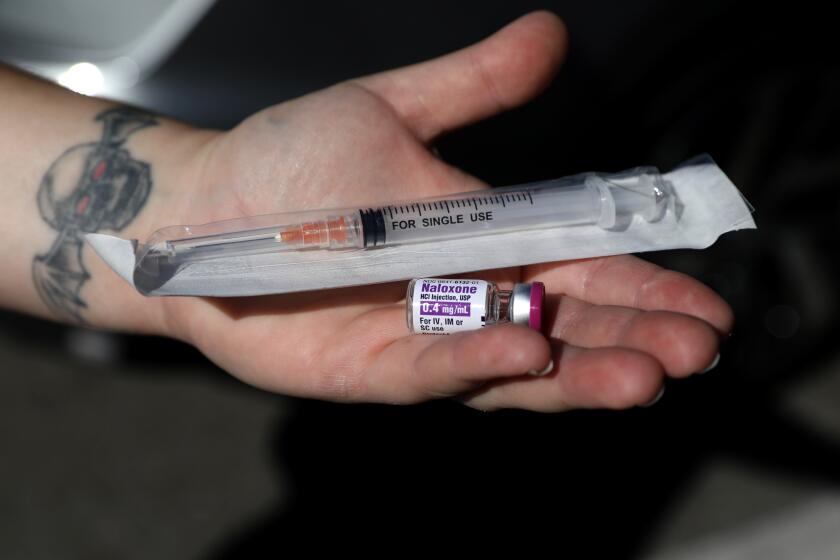

Instead, Compton suggested talking to teens about how they can help their friends in the event of a fentanyl poisoning or overdose, and having the overdose reversal drug naloxone readily available.

The state and L.A. County have worked hard to make Naloxone more widely available. One of the hurdles, though, has been the price of the inhalable version, Narcan.

While heroin use among teenagers remains relatively low, prescription pill use among young people is still “disturbingly frequent” because of the ubiquitous nature of the pills, according to Compton.

“The notion that pills are safe and always secure couldn’t be farther from the truth,” he said. “I often try to remind people that there’s a reason that it takes a prescription for these medications ... because while they can be very effective in the right circumstances, they also have significant dangers and side effects.”

The spike in fentanyl deaths among teens has touched all corners of the U.S., affected families and children across racial and class lines, and has risen to one of the top concerns for parents of middle and high schoolers.

At Helen Bernstein High School in Hollywood, 15-year-old Melanie Ramos died in September after she and her friend took what they believed to be a Percocet pill they bought from another student on campus. Police said the pill was actually fentanyl.

“I think we were failed in many directions,” said Gladys Manriques, 36, one of Melanie’s family members. “This pill is poison. I call it the devil pill, and it’s going to continue unless you start breaking down the chain.”

“People need to understand that this can happen to your family. If you haven’t been impacted by this yet, it’s just a matter of time.”

— Amy Neville, whose 14-year-old son Alexander died of fentanyl consumption

At least 16 students, including Melanie, have overdosed from drugs, both on and off campus, since the beginning of the school year, according to Los Angeles Unified School District Supt. Alberto Carvalho. Thirteen of those overdoses were from fentanyl, Carvalho said. One of the students was 17-year-old Cade Kitchen, a senior at El Camino Real Charter High School, an independent charter school in Woodland Hills that is not part of LAUSD. Cade, a former baseball player at the school, died from a suspected fentanyl overdose last month.

“The overdose numbers can be deceiving because the caveat is those are reported overdose cases,” Carvalho said. “If there is an overdose off school campus, where the parent seeks care at a hospital or the parents have Narcan, we may not necessarily have eyes on those cases. We believe what’s reported is a significant undercount of the true number of cases.”

LAUSD acts in response to overdose death of student at school. Also will step up parent outreach and peer counseling.

The district has tried to combat the fentanyl crisis by establishing a collaborative crime and narcotics task force with the LAPD and identifying areas in the city, such as parks, where drug transactions could take place. School officials have launched drug education webinars for parents and social media campaigns about fentanyl awareness. They also distributed two naloxone doses per campus to all middle and high schools in the district.

Among the most outspoken are parents whose children died from the drug.

In November 2019, Marin County resident Michelle Leopold’s 18-year-old son, Trevor, died. The freshman at Sonoma State ingested what he believed was Oxycodone one night before bed, and a friend who was sleeping over in his dorm room awoke the next morning to find his body.

For the record:

11:43 p.m. Nov. 12, 2022An earlier version of this story reported the wrong age for fentanyl victim Tyler Shamash. He was 19, not 17.

Beverlywood mother Juli Shamash said her 19-year-old son, Tyler, died in October 2018 while battling addiction to marijuana and codeine. Tyler was staying at a sober living home at the time and had been introduced to heroin, and then fentanyl, by one of his friends.

After trying fentanyl for the first time, Tyler ended up in the emergency room with overdose symptoms, but doctors didn’t test for fentanyl in his toxicology report, Shamash said. After he was released, his mother said, Tyler used fentanyl the next day and was found dead in the bathroom at the sober home.

“We always say, ‘Not my child,’ and those are the three most dangerous words a parent can say because of fentanyl,” Shamash said. “It’s not just kids with addiction who are dying — it’s kids who’ve never tried a drug in their lives.”

Rocklin, Calif., parent Chris Didier emphasizes “poisoning” instead of “overdose” when describing the death of his 17-year-old son, Zachary, in order to reduce the stigma around fentanyl.

Didier said his son died two days after Christmas in 2020 after ingesting what he believed to be a Percocet pill he bought through Snapchat.

“His death was not an addiction death,” Didier said. “He’s a kid who’s a victim of fraud. I don’t condone self-medication, and had he survived, I would’ve said, ‘What are you doing? You can’t take a drug or pill that’s not yours.’ Our young kids don’t deserve to die for making these kinds of mistakes.”

Roger Stock, superintendent of the Rocklin Unified School District, said that in the wake of Zachary’s death, the district has partnered with Placer County, the district attorney’s office, local law enforcement and mental health providers to launch a “One Pill Can Kill” awareness campaign. The district also bolstered its mental health services and will present a plan to the school board this month for deploying naloxone at all of its schools. Currently, police officers assigned to the district carry naloxone, but the district wants to make the medicine more readily available.

“I think we’ve always struggled, like society has, with drug use among adolescents. It’s not like it’s something that’s a new issue to grapple with,” Stock said. “However, with fentanyl, it’s really something that I’ve never seen before with the deadly impact.”

Jeannette Zanipatin, California state director for the Drug Policy Alliance, said she’s wary about increased law enforcement presence on school campuses because it could further stigmatize drug use and won’t get to the root of the problem. Instead, she urged access to public health interventions and other critical services.

She also noted that low-income Black, brown and Indigenous teens often don’t have the same access to healthcare and mental health services as other racial groups, causing them to self-medicate at higher rates, she said.

How to talk about mental health in a multigenerational Latino household

“Within communities of color and immigrant communities, mental health is an issue that is still stigmatized,” Zanipatin said. “How do we create conditions so that young people can seek the services that they need and can articulate what they’re feeling? We know so many young people are affected by the pandemic and had mental health issues exacerbated as a result of it.”

Alexander, who had always been a curious child, had been in a drug treatment program for pot in the past, his mother said. But his struggles really came to a head during the pandemic, she said, as he grappled with loneliness and boredom, relying on video games and social media to stay connected with his friends.

“People need to understand that this can happen to your family,” Neville said. “If you haven’t been impacted by this yet, it’s just a matter of time.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.