Child-care workers’ college costs covered under new San Diego County program

- Share via

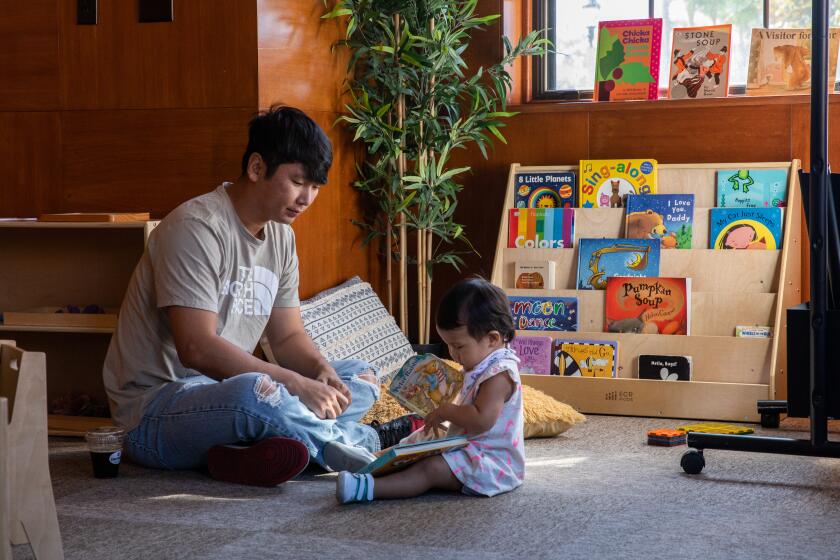

To improve the quality of child care and bolster an understaffed and underpaid child-care workforce, San Diego County education officials are paying $1 million for dozens of local early childhood teachers to get free higher education.

The initiative, launched this fall, covers the cost of tuition, books, fees and any other costs for an associate degree or child development permit for at least 80 child care workers in the county.

Get our essential investigative journalism

Sign up for the weekly Watchdog newsletter for investigations, data journalism and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Through state and local programs, some low-income and other students are able to attend community college with free tuition and other costs covered. But such programs have their limitations, such as being open only to full-time students. The program in San Diego County covers all costs involved in getting a degree or permit, and it is open to part-time students as well.

Officials expect the program to expand to support at least 100 more child-care workers as they forge more contracts with local community colleges, said Eunice Munro, director of early education programs and services at the San Diego County Office of Education.

The effort is meant both to improve the quality of early learning for kids and to bolster the child-care workforce, which has long suffered from low pay and staffing shortages. Those problems have made learning and care for young children scarce and expensive across California — including in San Diego County, where there are thousands fewer licensed child-care spots than there are young children of working families.

“There’s a big need for teachers working in early education, and we’re hoping that this program will address the highest of our needs by supporting qualified workforce members throughout our county,” Munro said.

Parents are struggling to pay escalating child care costs, as government and businesses try to expand availability

The San Diego County program is open to employees at home- and center-based child-care providers who receive state subsidies, are part of the county’s Quality Preschool Initiative or are located on tribal reservations. The program is funded by San Diego County’s First 5 Commission and a state grant.

California does not require early childhood teachers to have a college degree; it requires that teachers and supervisors have at least a dozen semester units in early childhood education.

Despite this, many early childhood workers have college degrees and child development permits, although education levels vary depending on the type of child-care setting and job title.

About 53% of home-based child-care providers statewide have an associate or bachelor’s degree, compared to 60% of assistant teachers and aides at child-care centers, 80% of center-based teachers and 89% of center directors, according to 2020 data from the UC Berkeley Center for the Study of Child Care Employment.

Parents of young children search for work-life balance after working through the pandemic.

Meanwhile, only about a quarter of home-based child-care providers have a child development permit. So do 41% of center-based assistant teachers and aides, along with nearly two-thirds of center-based teachers and center directors.

One of the biggest barriers to higher education for many child-care teachers is the cost, considering that child-care workers are often underpaid, Munro said.

Child-care teachers are over seven times more likely to be living in poverty than their K-12 counterparts, according to the UC Berkeley center. In 2019 in California, child-care workers made a median wage of just $13.43 per hour, according to UC Berkeley.

Rexie Reyes, a 24-year-old preschool classroom assistant in Lemon Grove School District, is receiving free tuition to earn a bachelor’s degree in child development through a joint program between Cuyamaca College and Point Loma Nazarene University. The program also paid for her to get books and a laptop to complete her coursework.

The creation of the first city agency focused on challenges facing youth was prompted by a lack of support during the pandemic

A native of southeast San Diego, Reyes decided she wanted to work in early childhood education after volunteering with youth programs like Big Brothers Big Sisters San Diego. She had taken courses at San Diego City College after graduating high school, then took a break from school when she had her own child.

Reyes said she still would have enrolled in Cuyamaca if she hadn’t received the tuition from the county but would have looked for some kind of financial aid elsewhere.

She plans to apply for a child development permit and become a preschool classroom teacher, and eventually a preschool coach.

“There is a lot of growth and opportunity within our district,” Reyes said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.