Column: At tiny-home villages in Eagle Rock and Highland Park, the report card is mixed

When I asked L.A. City Councilman Kevin de León how things were going at the Eagle Rock tiny-home village that opened in March, he had good news and bad.

Many encampments have disappeared, and those who had lived in tents are now in safe, clean quarters, with access to food and bathrooms. The councilman pulled out his camera to show me the “before” photos of people living in squalor, taking shelter under highway overpasses and fending off rodents.

But the tiny-home record is mixed so far, and De León told a story to illustrate his point. He said he was on his way to meet a friend for dinner in the neighborhood recently when he saw a storm of police activity at a gas station at Colorado and Eagle Rock boulevards.

“We have a gentleman who’s having a psychotic breakdown, and he has a blow torch,” De León recalls being told by an officer at the scene.

De León said the troubled young man appeared to be threatening to blow up his mother’s vehicle and the gas station.

“A psych team was there, trying to engage him,” said De León, but that didn’t work. So police fired less-lethal ammo and apprehended the man for a psychiatric commitment.

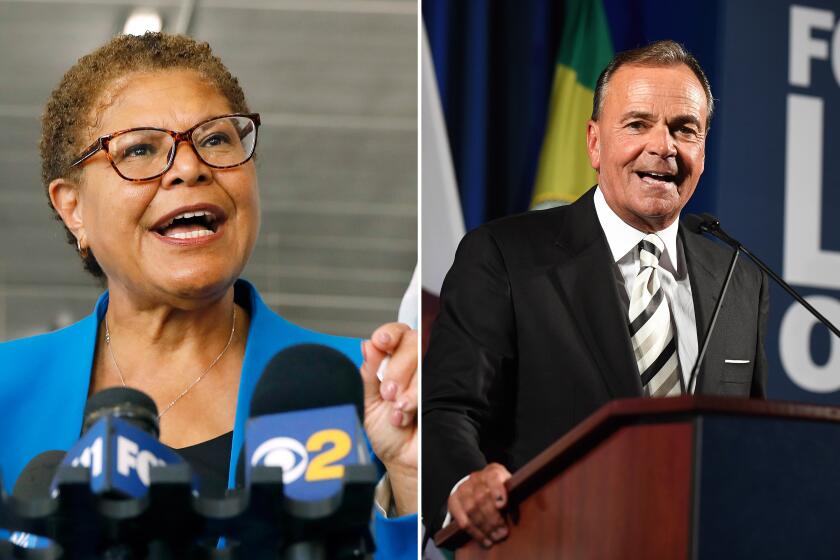

Mayoral candidates Karen Bass and Rick Caruso are providing details about their respective plans for addressing homelessness in Los Angeles.

When De León heard the man’s name, he thought, “I know him.”

The man had been a resident at the tiny-home village. Getting people in the door is hard enough, De León said. But redirecting the lives of people with severe challenges is complicated by a lack of desperately needed services.

“My staff and I, along with salt-of-the-earth social workers, are doing our jobs by getting people off the streets and putting a roof over their head,” De León said. “We need the county to do what they’re charged to do and provide the mental-health services and drug-treatment services our unhoused neighbors are crying out for.”

I had reached out to De León because it’s been almost six months of operation for the village in Eagle Rock and almost one year for the one in nearby Highland Park. And in the mayoral race, Rep. Karen Bass and Rick Caruso both have more tiny homes in their packages of homelessness fixes.

Caruso, as part of a nearly $1-billion plan that sounds ambitious at best and impossible at worst, says he’ll house 30,000 people in his first year. And 15,000 of them would be temporarily moved into tiny homes on 300 government parcels.

Even if he could pull off such a gargantuan task and figure out how to pay for it, a close look at the villages in Eagle Rock and Highland Park makes clear that getting someone in the front door is only half the battle.

I’ve requested the specifics and am waiting on a response from the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, but this much is known:

Some residents have been kicked out for rules violations. Some have chosen to leave. Some have received addiction and mental-health counseling, while others have not. Some have been moved into permanent housing or have taken up with family members, but many are still waiting in a long line for housing, and many of them don’t yet have the government vouchers needed for a permanent placement.

“To end homelessness for tiny-home residents and all of our unhoused neighbors, our community needs hundreds of thousands of affordable homes,” said Emily Andrade, director of interim housing for LAHSA.

Andrade said more mental-health and addiction-treatment resources are also needed.

I would agree. But what’s hard to fathom, De León told me more than once, is that with a county mental-health budget that runs about $3 billion, the streets are home to so many severely addled souls.

“You give me $3 billion, and I’ll have them off the streets,” he said.

One problem, other than the obvious failures of massive bureaucracies, is a long history of lousy coordination and outright feuding between city and county agencies. There was bickering this year after the city agreed but the county balked at settling a federal lawsuit over the handling of homelessness.

The county finally agreed several days ago to step up services for interim and permanent housing in the city, but the numbers are not likely to turn things around. For example, the additional substance-abuse and mental-health beds promised by the county is 300. At first glance, I wondered if a zero or two had been accidentally omitted.

“There are quite a few folks who don’t belong in tiny homes or Project Roomkey because they’re so severely mentally ill,” said De León. “They belong in a bed with the county … and the 300 beds agreed to is simply not enough.”

Jane Demian, homelessness liaison for the Eagle Rock Neighborhood Council, told me she knows the man who was apprehended at the gas station.

Get the lowdown on L.A. politics

Sign up for our L.A. City Hall newsletter to get weekly insights, scoops and analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“He has a history of schizophrenia, and he’s been on the streets a long time, and rather than connect him with mental-health services — which might not be available right now — they put him into a tiny home,” Demian said. “He did not do well because he needs a higher level of care, and this is what happens.”

And yet Demian told me she’s “cautiously optimistic” that the tiny-home villages will serve a valuable purpose for their residents and the community. As for the latter, she said, people are happy to see fewer encampments, but some who live near the villages have complained about drug use and other activity.

Demian regularly visits tiny home residents and said “the majority of them are happy they’re in there, although some would like more contact with their case manager and more services.”

Outside the tiny-home village in Highland Park, I met a guy who wished he could get through the gates.

“I liked it in there,” said Daniel, who told me he’d been kicked out for an altercation while defending his friend Candy.

Daniel told me he works as a security guard when he can, and to be close to Candy he sleeps in a friend’s car near the village. Both said they were among the first residents in November and expected to be moved into permanent housing by now. But the line is long, and they’re nowhere near the front of it.

On the street near the Eagle Rock village, Gary told me he’d been kicked out for an altercation and is back living on the street. Yesenia is still a resident and said she likes it in the village but wants more help with her mental illness.

Ron, who in March moved out of a motor home and into an Eagle Rock tiny home, seemed grateful for his humble abode.

“Some troublemakers have been kicked out, but everybody who’s still here has an advocate to help them, and they pretty much help us with everything,” said Ron, who told me that at 65, he couldn’t afford rent anywhere on the slim wages he makes in various odd jobs.

Ron said one much-needed improvement is more mental-health services for some of his neighbors, and he thought he’d have been lined up with permanent housing by now. But he doesn’t even have a housing voucher yet.

I asked if he knew when that might happen.

“Hopefully soon,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.