Karen Bass got a USC degree for free. It’s now pulling her into a federal corruption case

During the last decade, two influential Los Angeles politicians were awarded full-tuition scholarships valued at nearly $100,000 each from USC’s social work program.

One of those scholarships led to the indictment of former L.A. County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas and the former dean of USC’s social work program, Marilyn Flynn, on bribery and fraud charges.

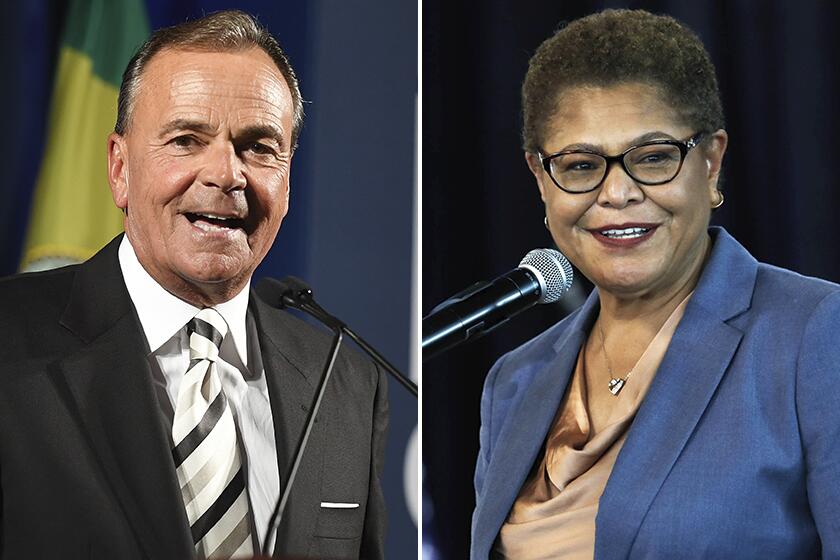

The other scholarship recipient, Rep. Karen Bass, is the leading contender to be L.A.’s next mayor.

Federal prosecutors have made no indication that Bass is under a criminal investigation.

But prosecutors have now declared that Bass’ scholarship and her dealings with USC are “critical” to their bribery case and to their broader portrayal of corruption in the university’s social work program.

When jurors ultimately decide whether to convict Ridley-Thomas and Flynn, prosecutors have indicated they want Bass’ relationship with USC, the largest private employer in her congressional district, to inform their verdict.

By awarding free tuition to Bass in 2011, Flynn hoped to obtain the congresswoman’s assistance in passing coveted legislation, prosecutors wrote in a July court filing. Bass later sponsored a bill in Congress that would have expanded USC’s and other private universities’ access to federal funding for social work — “just as defendant Flynn wanted,” the filing states.

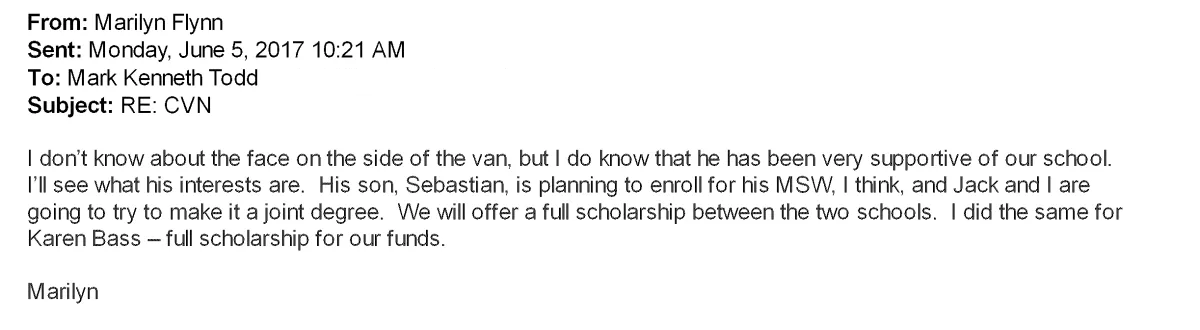

Flynn is charged for what prosecutors allege was a quid pro quo with Ridley-Thomas involving a scholarship awarded to his son in exchange for lucrative county contracts. To bolster their case, prosecutors have pointed to an email from Flynn in which she noted doing “the same” sort of scholarship-for-funding with Bass.

Bass’ name is redacted in much of the court filings, which prosecutors said accorded with Department of Justice policy. The Times confirmed her identity through case records, people familiar with the matter and some copies of emails that were briefly filed in court this summer and later redacted.

Federal prosecutors declined this week to elaborate on their statements about the scholarship. “At present and based on the evidence obtained to date, Rep. Bass is not a target or a subject of our office’s investigation,” said Thom Mrozek, director of media relations for the U.S. attorney’s office in L.A.

But with Flynn and Ridley-Thomas on trial in November, the circumstances of Bass’ free master’s degree could become an increasingly contested part of the case. In June, Flynn’s lawyers subpoenaed USC for correspondence pertaining to Bass’ scholarship and any honors or benefits given to the congresswoman, according to a copy of the subpoena filed last month.

A court battle over the involvement of Bass’ scholarship could in turn offer grist for political attacks as she heads into the final weeks of her mayoral campaign against developer Rick Caruso.

A former USC dean is charged with paying off Mark Ridley-Thomas in exchange for millions of dollars in L.A. County contracts with the university.

Through a spokesperson, Bass denied ever speaking with Flynn about federal funding for social work programs at private universities while the pair discussed her attendance at USC. Asked whether it was apparent that Flynn had a legislative agenda in offering the scholarship, Bass said, “No.”

“Everybody knows that the welfare of children and families has been a passion and policy focus of mine for decades,” Bass said. “The only reason I studied nights and weekends for a master’s degree was to become a better advocate for children and families — period.”

‘Clearly’ a gift

The Times revealed the Bass scholarship last year, noting that full-tuition awards like the one she received were not publicized, had no formal application process and were more generous than grants typically given to other students.

In an interview last fall for that article, Bass said that she didn’t apply for the social work program; Flynn apparently made the decision to admit her after learning of her interest in getting a graduate degree.

Before accepting the scholarship, Bass said, she wrote to the House Committee on Ethics in 2011, requesting an exemption on the rule prohibiting gifts to members of Congress. She told ethics officials the graduate degree would deepen her knowledge of child welfare policy and help her better represent constituents, according to congressional records.

The two leading members of the ethics committee at the time, Reps. Jo Bonner (R-Ala.) and Linda Sanchez (D-Whittier), ultimately concluded that although the scholarship was “clearly” a gift, and Bass’ status as a congresswoman was a factor in her receiving it, this constituted “an unusual case” justifying an exception, according to a letter summarizing the committee’s findings.

Bass enrolled in her first online class in early 2012, midway through her first term in Congress. The full value of her scholarship, about $95,000, was not listed in her annual financial disclosures until 2019.

Bass blamed the omission of tens of thousands of dollars in scholarship money on a former staffer. Asked if she reviewed the forms before they were submitted, she said, “Not necessarily .... And even if I did, that level of detail, I would not.”

Bass maintained in the interview that the scholarship played no role in her policymaking.

“I did not author any legislation that benefited USC,” Bass said.

A ‘hope’ for long-sought legislation

Flynn harbored longer-term plans for Bass in awarding the scholarship, according to federal prosecutors in L.A.

Pointing to emails and documents, prosecutors say Flynn hoped to advance legislation that “would provide more funding for the Social Work School by allowing private universities to receive matching grants for certain types of social work services.”

It’s unclear what legislation prosecutors are referring to; the name of the legislation is redacted in court filings.

However, the description tracks closely with the Child Welfare Workforce Partnership Act, which Bass sponsored in 2014. That bill sought to allow private universities like USC to obtain the same federal reimbursement to train social workers that public universities can.

After handily beating Rick Caruso in the June primary, Rep. Karen Bass has expanded her lead against the businessman, a new poll finds.

The role of Flynn, who led USC’s growing online social work program, in the development of the bill is not fully clear, but in court filings, prosecutors have contended that the former dean made her legislative goals known.

“With input from defendant Flynn, [Bass] ultimately co-sponsored [a bill], which made private universities like USC eligible for matching grant funds, just as defendant Flynn wanted,” prosecutors wrote.

The Times provided prosecutors’ court filing to the Bass campaign and asked what “input,” if any, Flynn provided. Bass did not answer the question.

Her campaign spokesperson provided a response from Bass’ former legislative director, Jenny Delwood.

“I don’t remember whether we heard from [Flynn] or not,” said Delwood, who is currently Bass’ campaign manager.

Delwood suggested that Flynn’s input in the Child Welfare Workforce Partnership Act would not have been critical since child welfare advocates, including a USC professor, Paul Carlo, had been calling for similar legislation since the mid-1990s.

Bass has maintained that it was Carlo’s encouragement that prompted her to propose the legislation, which did not make it out of the House of Representatives.

Of her dealings with Flynn, Bass said, “My interactions with her were no different than my interactions with any number of other education, business and nonprofit leaders.”

‘I did the same for Karen Bass’

When Bass graduated with her master’s degree in 2015, she was hugged by Flynn onstage — an embrace that few of the hundreds of others getting diplomas that day received, according to video of the ceremony.

By that time, USC’s social work school was booming, fueled by the online degree program Bass completed.

Run jointly with a for-profit digital learning company, 2U Inc., USC’s social work enrollment exploded, nearly quadrupling from about 900 in 2010 to 3,500 in 2016. Flush with cash, USC hired scores of new faculty and rented pricey downtown real estate.

Five council members blocked a proposal to name Heather Hutt as the interim representative of the 10th District, sending it to a committee for review.

But the explosive growth put more pressure to recruit new students, ease admissions standards and raise revenue, including from government contracts, The Times has reported.

Prosecutors say Flynn courted the then-preeminent powerbroker in L.A. County, Supervisor Ridley-Thomas, along with his son Sebastian, then a state lawmaker representing communities in South and West L.A. (Mark Ridley-Thomas was serving on the L.A. City Council at the time of his indictment.)

“I am going to have dinner with Mark Ridley-Thomas on Tuesday night,” Flynn told colleagues in a June 5, 2017, email discussing initiatives to help homeless veterans and funding needs.

“We will offer a full scholarship from our two schools. I did the same for Karen Bass — full scholarship for our funds.”

— Former USC Dean Marilyn Flynn

“There are significant amounts of county funds available, and I think we could make a difference,” Flynn added in the email exchange, which was filed in court.

“MRT has lots of discretionary money,” replied Mark Todd, a senior member of USC’s provost office, who floated putting Ridley-Thomas’ face on a mobile clinic serving homeless people. “He should give us $1M each year for three years.”

“I don’t know about the face on the side of the van, but I do know that he has been very supportive of our school,” Flynn responded. She said Sebastian Ridley-Thomas was planning to begin a master’s degree in social work, and perhaps it would be a joint degree with USC’s public policy school.

“We will offer a full scholarship between the two schools. I did the same for Karen Bass — full scholarship for our funds.”

In the months that followed, prosecutors have indicated, Flynn worked to secure a full scholarship for Sebastian Ridley-Thomas, and after he abruptly resigned his Assembly seat later in 2017, helped get him employment as a professor. At the same time, Flynn was working with the elder Ridley-Thomas to obtain contracts she hoped would generate millions of dollars annually in revenue.

Prosecutors cite the 2017 email exchange as key to illuminating the corrupt intent of Flynn’s dealings with Ridley-Thomas, and before him, Bass.

“In her email about defendant Ridley-Thomas and his son, defendant Flynn expressly acknowledges the quid pro quo — that she intends to offer the benefit of the full scholarship in exchange for funds for the School of Social Work,” prosecutors wrote in a July filing.

“Beyond that, she claims having done the exact ‘same’ in the past with the scholarship for” Bass, the filing said.

“I don’t know what that means,” Bass told The Times on Wednesday regarding the 2017 email written by Flynn. Bass reiterated that she “spent the time and effort” to earn a degree in order to become a better advocate for children.

Court records indicate that the circumstances around Bass’ scholarship could come into the trial as “other acts” evidence against Flynn and Ridley-Thomas, or what attorneys commonly describe as a “prior bad act.”

Prosecutors attempt to show jurors evidence of other related conduct in order to highlight a defendant’s motive, intent or modus operandi.

In this case, prosecutors stated that “the sole purpose for introducing” the Bass scholarship “is to establish defendant Flynn’s intent and provide necessary context.”

“Prior bad act” evidence is considered a potent courtroom tactic. Defense attorneys typically seek to exclude it before trial because of how prejudicial it can be to shaping a juror’s view of a defendant.

“The judge has to weigh the risk that a juror will say: ‘Bad guy. Did this before. I’m convicting’ versus understanding the permissible relevance of the evidence,” said Cheryl Bader, a former federal prosecutor and a law professor at Fordham University.

Presenting such evidence could also confuse jurors, Bader said.

“It could be very distracting,” she added. “You don’t want a trial within a trial.”

Prosecutors have been silent on what evidence, if any, they have showing Bass’ view of her scholarship, Flynn and any legislation sought by the dean.

Bass told The Times in a statement that she has not been asked to testify at trial.

A whistleblower emerges

USC has assumed an almost inescapable role in the mayor’s race, which will be decided in the Nov. 8 general election.

Early in her career, Bass worked at the university as a physician’s assistant and launched her nonprofit Community Coalition with help from USC. She also met regularly with USC leaders on their annual lobbying trips to Washington, D.C. — both during and after she completed her master’s degree.

Get the lowdown on L.A. politics

Sign up for our L.A. City Hall newsletter to get weekly insights, scoops and analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

A USC professor who supervised much of Bass’ studies, Wendy Smith Meyer, was also a donor to Bass’ campaigns who, along with her husband, former Warner Bros. chief Barry Meyer, have given $200,000 this year to an independent committee supporting Bass’ bid for mayor.

Her opponent, Caruso, is an alum and USC donor who was one of the nearly 60 trustees on the board when Bass received the scholarship.

Caruso became one of the most powerful figures at USC in 2018, when he was elected chair of the board of trustees following revelations of alleged sexual misconduct by a campus gynecologist. He stepped down as chair of the board earlier this year.

It was shortly after Caruso took over that a whistleblower came forward to report a suspicious $100,000 donation from Ridley-Thomas that was deposited into Flynn’s discretionary account. That money was in turn donated by Flynn to a nonprofit run by Ridley-Thomas’ son.

The whistleblower’s report triggered an internal investigation, culminating in USC lawyers alerting the FBI and the Department of Justice about the matter in the summer of 2018, according to an FBI agent’s summary filed in court.

Weeks later, after The Times revealed the $100,000 donation and scholarship to Ridley-Thomas’ son, Caruso told USC staff, alums and students in a letter about the “inappropriate financial transactions” by Flynn.

“The University disclosed this matter promptly to the United States Attorney’s Office and is cooperating with them,” Caruso wrote.

Caruso has long positioned USC’s actions in this case as an effort to turn the page on past scandals. In an interview earlier this year, he dismissed the notion that his political ambitions four years ago factored into the university’s handling of the matter.

“I have no influence over the U.S. attorney’s office,” Caruso added. “I didn’t handle turning any documents over to the U.S. attorney’s office. That was all done by our general counsel.” ”

Supporters of Caruso have already made Bass’ scholarship an attack point.

Earlier this year, a political action committee sponsored by the L.A. Police Protective League began airing ads saying that after receiving free tuition for her master’s degree, Bass “repeatedly voted to give USC millions in taxpayer funds.”

The police union’s committee also set up a website highlighting Bass’ free tuition.

Bass’ lawyer, Stephen Kaufman, sent a cease-and-desist letter to L.A.-area television stations over the ads, calling them “false, misleading and defamatory.” Her campaign said the bills that Bass voted on and were cited in the ad had funded entire federal agencies, not specifically USC.

For Flynn and Ridley-Thomas, who have pleaded not guilty, further campaign ads about the scholarships have already become an issue in their bid to avoid prison.

In his lawsuit, Ridley-Thomas called the move by Controller Ron Galperin to cut off his pay “unlawful, unauthorized and politicized.”

Flynn’s lawyers cited the ads as one reason to move the trial to mid-November, after the election. Her lawyers said the ads “prominently and negatively feature” the former dean and would make jury selection “more difficult and time-consuming.”

Ridley-Thomas’ lawyers disagreed, and unsuccessfully sought to have the trial begin earlier this summer.

“The recent political attack advertisements currently airing on television are a real concern,” Ridley-Thomas’ lawyers wrote.

“But it is not clear why continuing the trial to November 15 — two weeks after the general election, during which the frequency of these advertisements will likely only increase — will make voir dire and jury selection any easier.”

Times staff writers Harriet Ryan, David Zahniser and Dakota Smith contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.