Column: We’re days away from a Diablo Canyon decision. Here’s why one side has a better argument

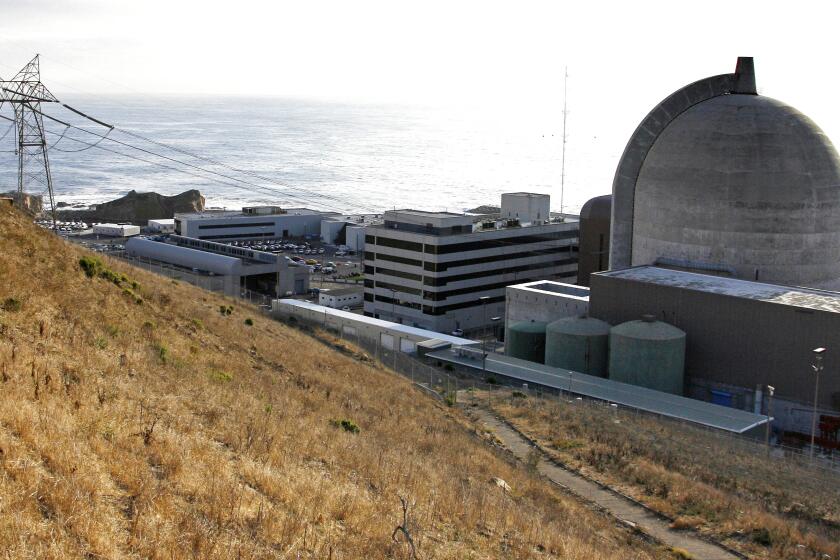

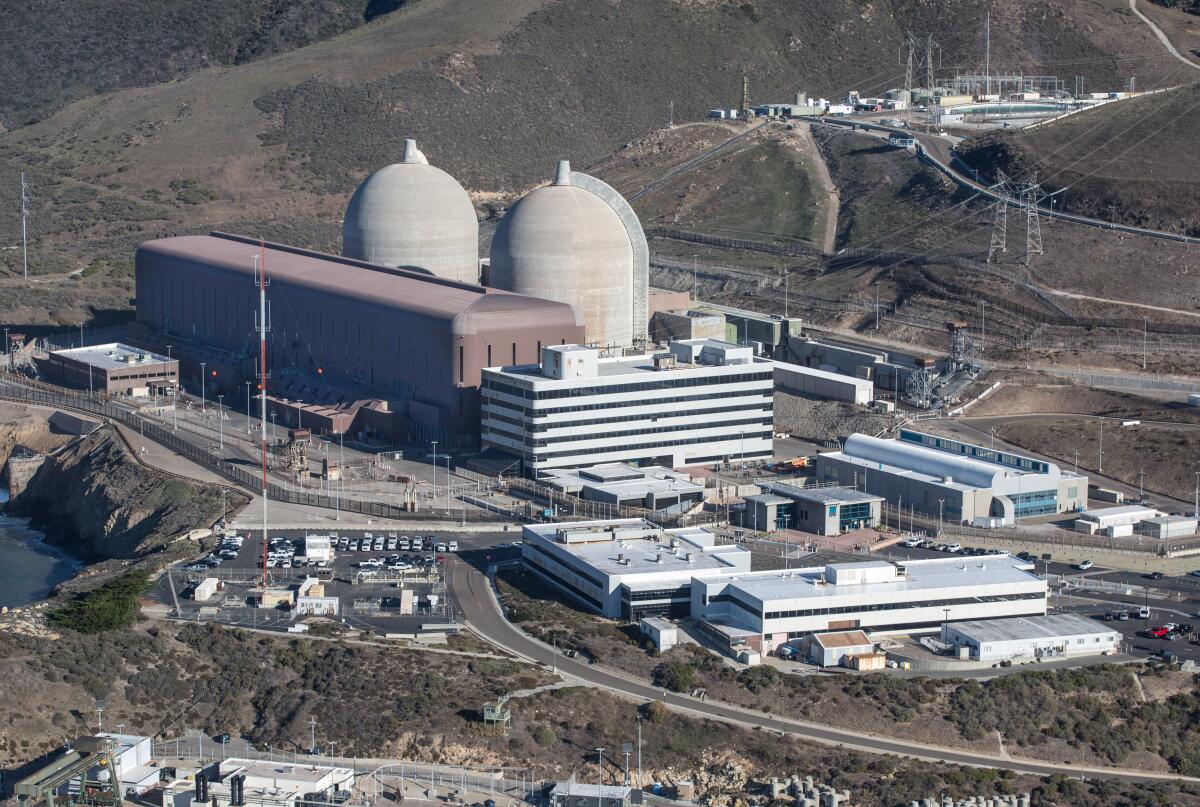

SAN LUIS OBISPO — Should California extend the life of the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant?

On my visit to the Central Coast, I heard a resounding yes.

And a resounding no.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s last-minute legislative push has some people cheering, while others derisively refer to him as Gov. Nukesome.

It’s almost as if we’ve turned the clock back to when the controversial plant was about to open and thousands protested. If you’re of a certain age, you might recall a group called the Abalone Alliance shaking a fist way back in 1981, and rocker Jackson Browne getting cuffed.

The latest meltdown, if you’ll forgive the term, comes because as the legislative session draws to a close, Newsom is trying to rush a bill that would extend the nuclear plant’s life until 2035, if not beyond, despite a long-established agreement to turn out the lights in 2025. Newsom would also waive environmental reviews and dangle $1.5 billion in taxpayer money for plant operator PG&E.

So what gives?

The working explanation for the governor’s change of heart is his administration’s contention that we don’t have enough wind and solar power in place to keep the lights on during peak demand, so it’s worth keeping Diablo Canyon open. Especially because unlike the dirty natural gas that powers half the state’s energy supply, nuclear is clean.

If it occurred to you that politics might be in play, you’re not alone. Both supporters and foes I talked to noted that then-Lt. Gov. Newsom was anti-Diablo in 2016 when he had an eye on a run for governor, and he’s now pro-Diablo when he might have an eye on a run for president — an ambition that could be torpedoed by blackouts.

But politics aside, a lot is at stake, especially in San Luis Obispo County. PG&E employs more than 1,000 people at Diablo Canyon, and a poll early this year found nearly 75% support in the county and more than 50% in the state for keeping Diablo Canyon open.

Passions are hot on both sides, though, and have been for years.

You’ve got Mothers for Peace and Mothers for Nuclear, with both sides claiming the environmentalist mantle. You’ve got the Alliance for Nuclear Responsibility and Californians for Green Nuclear Energy. Professors, scientists and policy experts in and beyond the Central Coast are also divided.

Let me start with the folks who want to keep Diablo Canyon running. Their basic argument is that as we suffer the consequences of burning fossil fuels to power our vehicles and pollution-spewing energy plants, it’s insane to shutter a carbon-free plant that has operated without major incident since opening in the mid-1980s.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom is urging the Legislature to pass a bill enabling the Diablo Canyon nuclear plant to stay open for another decade.

“This is an extremely safe plant, and it is well engineered,” biophysicist Gene Nelson, a former college professor, told me over breakfast at the Madonna Inn. He was wearing a green headband and a Californians for Green Nuclear Power T-shirt. “If the Big One hit,” Nelson said, “I would love to be at that plant when it happens, because it’s the safest place in San Luis Obispo County.”

Others disagree about that, but Nelson hardly took a breath and barely touched his French toast while making his case that what Diablo Canyon safely produces is clean, reliable and cheap (the last point is open to debate). Put that up against the pollution-spewing plants across the state, he said, and it’s no contest.

“Wind and solar have a secret friend, and it’s natural gas,” Nelson likes to say. What he means is that there isn’t now, and won’t soon be, enough wind and solar power — which have their own environmental impacts — to put dirty power plants out of service.

After breakfast, I met for coffee in Avila with Kristin Zaitz and Heather Hoff of Mothers for Nuclear. They both work at Diablo Canyon (Zaitz is a civil engineer and Hoff writes procedural policies), and each of them was once highly suspicious of nuclear.

“I was going to go in there and be the Erin Brockovich of nuclear energy,” said Hoff, who had intended to expose the dangers of Diablo Canyon just as Brockovich highlighted the dangers of contaminated groundwater near a PG&E plant in the Barstow area.

But after getting in the door, Hoff and Zaitz were turned around. They concluded that they had bought into unwarranted fears and misconceptions about nuclear power, and they came to believe you cannot be opposed to nuclear power if you care about climate change.

Hoff’s electric car has a bumper sticker that says “Split Don’t Emit!” (split as in atoms) — and both she and Zaitz have tried to calm public fears.

Zaitz said nuclear power aligns with both her “environmental and humanitarian” concerns and she can’t understand why there isn’t more outrage over the pollution and disease caused by dirty power plants.

They and other supporters of Diablo Canyon have been buoyed by President Biden’s offer of billions of dollars to keep nuclear power plants open longer as part of a broad plan to reduce carbon emissions. And their arguments are persuasive, to a degree.

But the opponents make what strike me as stronger arguments.

The Diablo Canyon plant sits on and near several earthquake faults, not all of which were adequately considered when the plant opened. It sucks in millions of gallons of seawater daily for cooling and spits out warmer water, killing some fish and altering the marine environment.

And then there’s the possibility of a Chernobyl- or Fukushima-type disaster, along with the unanswered question of where to safely store nuclear waste.

“Accidents don’t happen frequently, but when they do, they’re catastrophic,” said Linda Seeley, who is with Mothers for Peace and is on the decommissioning panel that has spent several years planning the phaseout.

Seeley told me she’s been accused of being a “scaredy cat,” and she pleads guilty as charged.

“We understand the danger of nuclear waste and the fact that there’s nowhere to put it,” she said.

It’s not just a question of nuclear vs. non-nuclear, Rochelle Becker, director of the Alliance for Nuclear Responsibility, told me while we walked a breathtakingly beautiful coastal trail near Diablo Canyon. It’s a question of whether it makes sense to reverse course so jarringly after years of planning a closure that was agreed to in 2016.

And who was in on that deal, six years ago, to begin the phaseout?

All the interested parties, basically, including PG&E, the main labor union, the Legislature and then-Lt. Gov. Newsom. In fact, Diablo Canyon employees got 25% pay bumps in anticipation of employment transition after the closure.

Six years later, it’s not even clear that PG&E wants to keep Diablo Canyon open, although it might be hard to resist grabbing the big taxpayer handout Newsom is floating. Some legislators have considered introducing a competing bill that emphasizes renewables rather than nuclear, but it wasn’t clear that would go anywhere.

“I just can’t quite understand it,” said Becker, who predicts that maintaining an aging plant could produce ever-rising costs that ratepayers and taxpayers are stuck with.

On our walk, Becker more than once referred to PG&E as a felon. The company pleaded guilty two years ago to 84 counts of involuntary manslaughter for sparking the deadly Camp fire.

Billionaire Phil Anschutz — who owns the Coachella music festival, the Los Angeles Kings hockey team and L.A.’s Crypto.com Arena — is preparing to build the nation’s largest wind farm. We traveled the route.

And yet, Becker said, despite the utility’s checkered past, the governor’s proposal would lift environmental reviews. She and others are livid that Newsom used a legislative procedure that left little time for discussion and review.

“Basically,” said Andrew Christie of the Santa Lucia chapter of the Sierra Club, “this looks like somebody trying to ram through a bill as fast as possible.”

Actually, there was a Senate committee hearing on the governor’s proposal Thursday afternoon. But listening to it, I had the feeling that months’ worth of important questions about energy policy and public cost were being hustled into a criminally short amount of time.

Legislators took about three hours to question a Newsom staffer. Public comments, which were as divided as those I heard on my visit, ran another hour. And I didn’t hear compelling evidence that come 2025, the state power grid will still need Diablo Canyon. The next day, the Assembly raced through its own hearing as the clock ticked on the legislative session — one rush job following another.

If the governor and legislators had moved with this level of urgency to bring more renewable sources of energy online, we wouldn’t be having this conversation.

“If you say you’re going to put billions of dollars in taxpayer money … into keeping this plant open, that’s telling people who want to build efficient renewables, don’t bother,” said Amory Lovins, a Stanford professor of civil and environmental engineering.

By the way, whether Newsom’s extension is approved or not, Diablo Canyon is going to be open for three more years. That gives us time to accelerate the inevitable conversion to the energy of the future, rather than invest in the energy of the past.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.