- Share via

SAN DIEGO — In a cry for help, UC San Diego students turned to the school’s administrators last year and posed three questions that crystallized the severity of a campus housing shortage long in the making.

Could the school provide air mattresses for couch surfing? Or turn a gym into a temporary hotel? Or give students money to book an Airbnb?

This story is for subscribers

We offer subscribers exclusive access to our best journalism.

Thank you for your support.

COVID-19 had forced UCSD to thin out its dorms, helping push 3,200 students on to waiting lists. But the bigger causes were the school’s spectacular growth, and the lack of affordable housing near campus.

Another shortage looms. UCSD estimates that it will welcome a record 44,000 students this fall.

Chancellor Pradeep Khosla hopes to resolve the matter with a singular stroke.

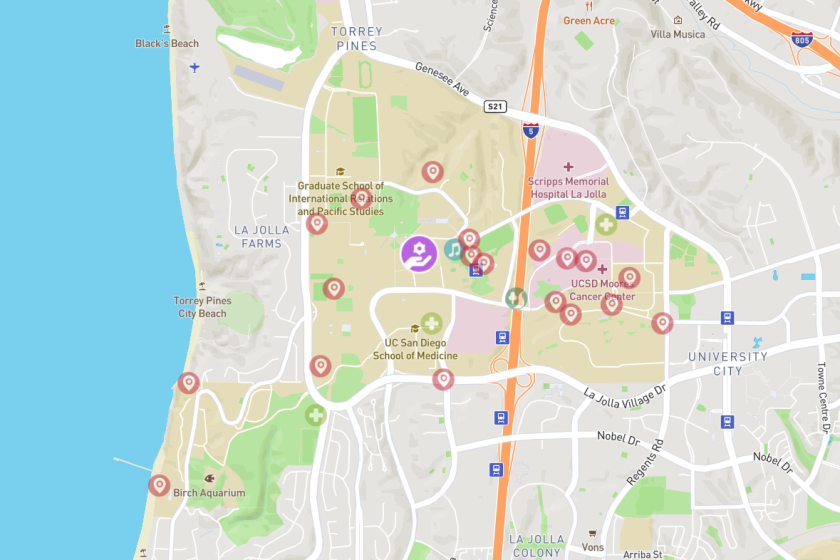

As he finishes his 10th year as chancellor, Khosla says he’s leaning toward nearly doubling UCSD’s housing capacity to about 40,000, in a plan that could include lodging near Blue Line trolley stations, possibly stretching all the way through South County.

That’s higher than the number of people who live in downtown San Diego and would enable UCSD to house most of the 50,000 students it expects to have by 2032.

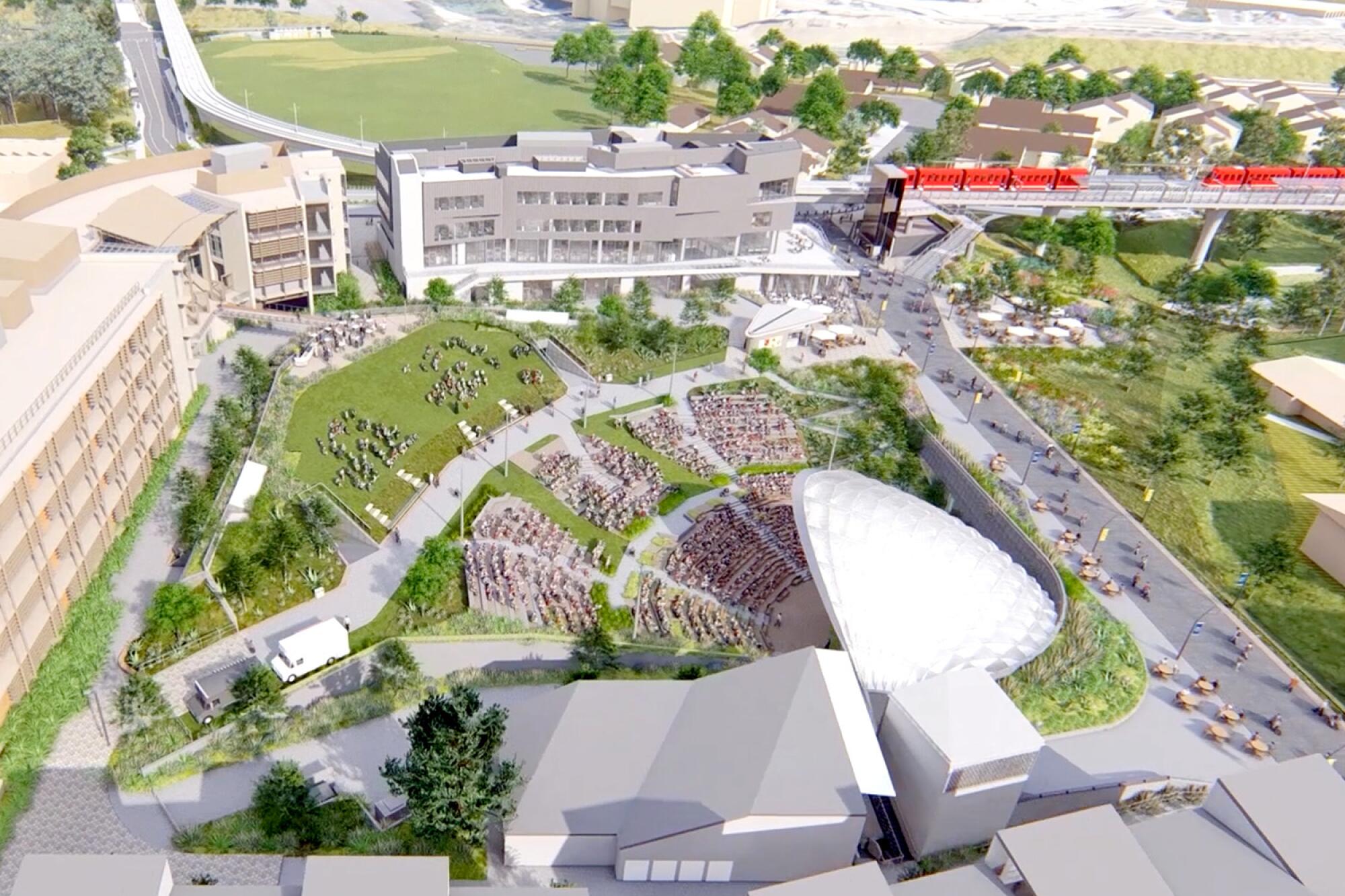

Aerial view of a UCSD village under construction

The plan would cost billions and would be in addition to a roughly $8.5-billion expansion that’s already underway across the university.

Khosla disclosed the idea during conversations with the Union-Tribune before this weekend’s commencement ceremonies, during which a record 8,300 students are eligible to get diplomas.

The timing of the announcement was unexpected. The boldness of the move was not.

The chancellor is a grow-big, grow-fast, grow-now engineer who is focused on the purpose of it all.

The University of California’s nine undergraduate campuses are facing unprecedented demand for access from prospective freshman and transfer students and need to greatly expand — stat. The system received nearly 211,000 applications from prospective freshman for the coming fall quarter.

The 65-year-old Khosla often quick-walks across campus, so filled with enthusiasm you half-expect him to pull blueprints out of the dark suits he favors. On a recent morning he peered at a towering dorm rising in the mist and said, “Go to the top of the building. You can look at Tijuana. You can look at Catalina. You can look where the Earth curves.”

He then noticed an directional sign and said: “I’ll call [staff] and say, ‘How come that sign is not big enough?’ They get upset at me, saying, ‘You’re micromanaging.’

“I’m not,” he added. “I’m a customer. I’m paying the bill.”

Khosla is skilled at sharing his wants, desires and vision, as Assemblyman Kevin McCarty (D-Sacramento) learned when he joined the chancellor on one of those walks.

“If you ask an academic what time it is, some of them will tell you how to build a clock,” he said. “Pradeep knows how to talk to people. He gives you a crystal clear path of what you might do together.”

That walk-and-talk helped lead McCarty to successfully seek state funding to build housing at public colleges and universities. So far, UCSD stands to get $100 million out of a pool that will initially total $500 million and could later rise to $2 billion. McCarty also is pushing a related measure that would provide schools with a total of $5 billion in interest-free loans to build housing. The proposal was heavily influenced by Khosla.

The chancellor also has raised $3 billion in private donations over the past decade, leading one observer to say, “It’s like he plucks money out of the sky.”

Much of this arises from Khosla’s soft-touch way of courting people. But not all of it. Geneticist Craig Venter, who recently sold UCSD a research building for $25 million, says the chancellor’s private negotiating style can be “my way or the highway.”

There have been missteps.

During last year’s housing shortage, Khosla publicly said, “We did the best we could. It is what it is.” A lot of students are still fuming over that remark, and he knows it.

The chancellor, who lives in a large, university-owned home on the bluffs above Blacks Beach, acknowledges how “crazy” the off-campus rental market has become, and how determined he is to build more campus housing to alleviate the pain.

His mantra is “no parking lot gets a view.” Which is to say that parking will go underground, leaving space for tall buildings, many of them dorms. A campus that’s long been mostly a small town hidden by eucalyptus trees is becoming a city with its own skyline.

During his first decade, Pradeep Khosla has built, started, planned and purchased buildings, bridges and special projects at an estimated cost of $8.8 billion.

Crunch time

The skills Khosla is using to advance UCSD were developed long ago and dovetail with San Diego’s ever-expanding interests in biotech, defense, energy and computer science.

He was born into a middle-class family in Mumbai, a city that’s home to many of that country’s leading science centers. His father sold wallpaper, and his mother taught high school English.

Khosla focused on education, earning a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering at the elite Indian Institute of Technology in 1980. He had the option of studying medicine but hated the sight of blood.

He moved to the U.S. later that year and earned a master’s degree and doctorate at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, a school that became a pivotal player in the rise of the internet, Wi-Fi, artificial intelligence and software that does such things as match living kidney donors to patients.

Khosla was part of that rise. He joined the faculty and specialized in robotics. At one point he took a break from Carnegie Mellon to help the federal government do research that would contribute to the evolution of the sort of unmanned aircraft that are developed in San Diego by General Atomics and Northrop Grumman.

He went on to become CMU’s engineering dean and proved his knack for fundraising by raising $90 million for a major engineering center.

Khosla turned out to be what UC Regents were looking for. They appointed him chancellor in 2012, putting him in charge of a campus that was struggling to reach its potential.

UCSD’s enrollment was flat, about 28,000. State funding for the UC system had been falling for years. The Great Recession of 2008 made things worse. And Gov. Jerry Brown and UC President Janet Napolitano were soon fighting over money.

She wanted a lot more of it. He wasn’t feeling that generous.

Khosla looked to the future and thought that enrollment might someday reach 42,000, maybe a bit more. But that day wouldn’t arrive until 2035, at the earliest.

Or so he thought.

Things changed when the public began pressing the UC to expand. More California high school students were meeting the system’s eligibility requirements. And more were applying for admission, including to UCSD, which was turning heads by raising more than $1 billion a year for research.

Khosla responded by heavily recruiting non-California residents, who pay far higher tuition. His main target: China. Enrollment exploded, producing revenue that helped underwrite UCSD’s budget and partly covered the cost of adding more California students.

By fall 2021, in the midst of a pandemic, UCSD’s enrollment had climbed to nearly 43,000, producing a shortage of housing, classrooms and parking.

Other UC schools — notably UCLA and UC Berkeley — followed a similar recruiting strategy, attracting the attention of Assemblyman Phil Ting. He didn’t like what he saw.

The schools “focused on admitting out-of-state students at the expense of in-state students,” Ting, a San Francisco Democrat, told the Union-Tribune last year. “They deny that. But if you just look at the numbers, it’s pretty clear.”

The Legislature ordered UCSD, UCLA and Berkeley to reduce the percentage of non-California students it enrolls, costing the system millions. By then, though, California had a new governor, Gavin Newsom, who is making historic investments in the UC.

Grow-mentum

A short time later Khosla dropped a bombshell, telling the Union-Tribune’s editorial board, “I can actually imagine we could be a campus of 50,000 students ... There’s clearly a pressure to grow.”

The remark came as the Metropolitan Transit System was preparing to open the Blue Line Trolley extension it built between San Diego and La Jolla, a link that includes two stops at UCSD. Khosla strongly backed the project. But he didn’t fully appreciate its potential until he rode the trolley a couple of times.

“I saw the wilderness through which the light rail was going, which you never see (from Interstate 5) ... ,” Khosla said. “I’m thinking, this is San Diego. We’ve got multiple crises (including housing). We should be developing this.”

The remarks represent a tectonic shift in thinking.

Historically, UCSD has been largely content to exist as an isolated Eden on the bluffs of La Jolla, largely shielded from sight by its terrain and proximity to the ocean.

Khosla doesn’t share that attitude, saying that UCSD should incrementally expand south to better serve the region. It led him to build Park & Market, an events and education center that recently opened on the Blue Line in the East Village. The chancellor said he is not actively planning on creating an academic-oriented satellite campus there, but has not ruled out the idea.

He’s already in expansion mode.

Khosla is negotiating to buy Framework, a new 87-unit apartment building two blocks away at the corner of 13th and F streets that would be used to house faculty and staff. A second housing complex is a possibility.

He also is considering acquiring or developing housing farther south.

“Anything proximal to every Blue Line stop, in my mind, is a logical extension of this campus,” Khosla said.

His backers include Rich Leib, chairman-elect of the UC Board of Regents.

“Pradeep can marshal the forces UCSD needs to increase capacity,” said Leib, a San Diego businessman. “We need to bring in more students, educate them, get them on the job market.”

Cry uncle

Where is this all leading?

The university’s neighbors want to know. The super-competitive rental market in La Jolla-UTC is getting pricier, in part, because students are competing with everyone from biotech workers to nurses to accountants for a place to live. The average monthly rental for a studio in that area is $2,270. It’s $2,686 for a one-bedroom, $3,609 for a two-bedroom, and $4,412 for a three.

“Khosla should just tell us how big the school is going to get so we know how much traffic and noise to expect,” said Robert Patterson, a wealth management expert who lives in University City.

The chancellor has built, started or planned more than 25 major projects, including the nearly $1-billion Jacobs Medical Center. He built a bridge across Interstate 5 to link the hospital and other core health and medical facilities to the main campus, during a period when enrollment jumped by about 14,500.

Construction is underway on the first of six dormitories that will range from 16 to 23 stories tall, and he plans to seek approval for a village that can house 4,000 students, which is roughly the population of Del Mar. The complex is likely to cost upwards of $1 billion.

The university also bolstered its already large healthcare system, which has given at least one COVID-19 vaccine shot to about 370,000 patients, a number that’s far higher than all of the UC’s other four major health programs.

An outdoor amphitheater that can hold nearly 3,000 people will open in October, not long after a $185-million engineering center debuts nearby.

Khosla’s grand development plan is drawing mixed reviews from students.

The Union-Tribune discussed the boom with 20 of them. Some liked it. Others said the campus is growing too fast. Some also described Khosla as a remote figure who isn’t fully tuned in to their concerns.

“Students are in a constant state of transition and turmoil,” said Sophia Nguyen, a senior. Getting admitted “doesn’t necessarily mean they will get a good or high-quality college experience.”

Troy Tuquero, another senior, said: “Do we have the housing that’s necessary? Do we have the staff to manage that? I don’t think the university is showing that there’s a meticulous plan.”

Hayden Schill, a graduate student, said, “I don’t think the chancellor is empathetic toward students.

“You have to care that the new grad housing units recently built are unaffordable to many, care that students are looking to the university for a kind of leadership that invests in a clean future they need but don’t see it, care enough to invest in mental health resources for students, and so on.”

The disconnect between students and the university was particularly evident in July when the school sent thousands of undergraduates an email saying that UCSD had run out of available housing.

Nearly all of the recipients are members of Generation Z, or Zoomers, digital natives who generally don’t like, trust or read email, say demographers. Some learned of their plight only because their parents got the same email.

“My generation has been raised with more hand-holding than earlier generations,” said Manu Agni, a Gen Z-er who just finished a stint as president of Associated Students.

“The university has isolation housing now for students who get COVID. Students expect the university to call them, pick them up, put them in a van and take them to a hotel and give them three meals a day.”

Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education in Washington, D.C., doesn’t regard Khosla as callous or out of touch.

“There are university presidents and chancellors who demonstrate their student centered-ness by being visible, talking with students, solving ‘pot hole’ problems,” said Mitchell, who has known Khosla for years.

“And there are people for whom this is not as effective a use of their time as moving the ‘big rocks.’ Pradeep is a big rock guy. I think that’s highly admirable.”

Rajesh Gupta, founding director of UCSD’s Halıcıoğlu Data Science Institute, agrees.

“Pradeep has to seize the moment,” he said. “It will make UCSD ‘The Cal’ of Southern California, just as Berkeley is ‘The Cal’ of Northern California.”

C’mon down

People have long joked that UCSD’s initials stand for University of California Socially Dead. Things have improved a bit as enrollment soars. But doubts remain about whether Khosla, a foodie who loves to socialize, will ever achieve one of his biggest goals: turning the university into a major public destination that’s as beloved as Balboa Park and the Gaslamp Quarter.

UCSD doesn’t have a clearly defined entrance. It rarely stages events that broadly appeal to the public. There’s no clutch of fun restaurants. The main trolley station empties into a construction zone. Parking is a nightmare.

And the school gives off chilly vibes. There’s a sign posted outside Prebys Concert Hall that says: “No congregating in courtyard without Music Dept. authorization. This includes: music, dance, performance, and skateboarding.”

In that way, UCSD is the antithesis of the University of Arizona in Tucson, where a lively entertainment and retail district that’s served by a jump-on, jump-off trolley leads to the school’s big front gate, which is flanked by public parking that’s close to the school’s museum, planetarium and sports arenas.

Khosla was asked recently whether he should consider hiring a public events director. He lit up, saying UCSD is in the process of doing just that, which will enable the school to regularly host everything from sizable outdoor concerts to food and art festivals.

He promised results: “Nobody believes a leader on Day One. But over time they do.”

Robbins writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune. Union-Tribune staff writer Phillip Molnar contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.