SAN DIEGO — Inside a tent buffeted by the wind, Tara Stamos-Buesig unpacked her testing kit, hoping the shifting hues of its chemicals could help her save a life.

Billy, a 38-year-old who first started using oxycodone as a teenager, handed her a set of baggies labeled “ketamine,” “heroin,” “crystal meth” and “fentanyl.” Stamos-Buesig hunted for the right bottle of chemical reagents to mix with each sample. She scrutinized one baggie after a few drops of reagent had mixed with the sample, tapping a polished fingernail to the corner.

“Did you guys do the ketamine?” she asked Billy and his girlfriend. Not yet, they answered. “I want to see if it has meth in it.”

Stamos-Buesig began hitting the streets last year with a testing kit, purchased online from the nonprofit DanceSafe, as her own nonprofit was getting off the ground. She has brought its telltale chemicals to tents and hotels, concerts and parties, toting it in a black box from Walmart made for ammunition. Her phone rings late at night as people search online for “drug checking.”

“They’re not trying to die,” said Stamos-Buesig, founder and executive director of the Harm Reduction Coalition of San Diego, which runs a mobile program that provides clean syringes and other supplies to protect the health of people who use drugs. “They’re attempting to keep their use at a manageable level and stay alive.”

As deaths from drug overdoses have hit record highs, claiming an estimated 107,000 lives last year across the United States, many public health advocates, researchers and activists are pushing to help people find out what is in their drugs — and use that knowledge to reduce their risk.

Fentanyl, the powerful synthetic drug that has driven up opioid overdoses, can be detected simply with test strips. But as the drug market has grown increasingly messy and complex, many want to go further, analyzing the makeup of illegal drugs with more sophisticated tools to identify known and new dangers.

Drug deaths are often tied to more than one drug. The year before the pandemic began, nearly half of deadly overdoses across the country involved a combination of fentanyl, cocaine, heroin or methamphetamine, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analysis found.

For years, this Canadian city has hosted safe consumption sites for addicts. They’ve saved lives, but with some painful tradeoffs.

Meth is being mixed with opioids with deadly results: Federal data show that as of 2020, more than 60% of overdose deaths involving methamphetamine also involved an opioid, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

And in Los Angeles County, there has been a massive increase in the percentage of deadly overdoses among homeless people that are tied to two or more drugs, with multi-drug deaths rising to 60.2% from 37.4% of overdose deaths among unhoused people between 2014 and 2020, according to data from its public health department.

“We’ve used forensic chemistry for decades to tell people what’s in drugs after it’s too late,” said Nabarun Dasgupta, senior scientist and innovation fellow at the University of North Carolina’s Gillings School of Global Public Health, where researchers are analyzing drug samples submitted by mail. “What we’re trying to do is not wait that long.”

Stamos-Buesig spent years on the streets herself before she stopped using heroin and meth and went back to school. “There’s nothing different between me and them, except that I’m not there any more,” she said, gesturing to the tents around her as she visited an encampment. “So I come out here. And I carry water into the fire every day.”

When Stamos-Buesig arrived at a row of tents near a big-box store in San Diego and unpacked her testing kit, David Amrani stepped forward with a scrap of foil. Amrani said that when he first began using fentanyl, he had no idea he was using fentanyl. “I’d wake up dope sick and not realizing how,” the 35-year-old said, “because all I was doing was crystal.”

Stamos-Buesig unfolded the foil and crumbled a bit of residue into an empty ice cube tray to check if it was meth. “We’ll know by the color change,” she told Amrani, eyeing the squirt of reagent in the tray. As Amrani waited, Stamos-Buesig sprinkled another sample into a container of water, which she checked for fentanyl using a test strip.

The results indicated that it contained both meth and fentanyl, as Amrani had expected this time. Stamos-Buesig wondered aloud, based on the particular hue that the reagent had turned, if the drug might also contain heroin, which could take another sample and a squirt of another reagent to suss out.

Fentanyl is popping up in many kinds of drugs, but testing solely for fentanyl can miss other hazards. Stamos-Buesig has found that a drug believed to be ketamine — an anesthetic sometimes used recreationally — instead contained meth and cocaine. Her kit can identify a range of known drugs including meth, cocaine, oxycodone and heroin and also check for some adulterants like aspirin or sugar.

If people know what they are using, she said, they can adjust their plans. Knowing what they are using can also make it easier to detox with the help of medication.

Sometimes “you still want to do the drug,” said Zachary Markovich, 32, who gets supplies from the San Diego group. But instead of shooting up, “maybe you’ll just smoke it,” which makes it easier to gauge the effect and stop after a smaller dose. “It’s not jumping into the deep end — you’re tiptoeing in.”

Drug mixing is nothing new, but experts warn that its dangers have accelerated as the drug supply has become littered with fentanyl and other synthetic compounds.

Fentanyl has unseated heroin in the illicit market because it is cheaper to make, much more powerful, and is not tethered to agricultural production, said UCLA addiction researcher Joseph Friedman. Because it is so potent, drug suppliers have cut the powder with other substances. And as drug production has shifted toward synthetic drugs, chemists can more readily produce new ones.

“Now that things are in the lab, it’s very easy to make way more compounds, very quickly,” said Bryce Pardo, associate director of the Rand Drug Policy Research Center. New chemicals might be discovered in the plant world every five years or so, Pardo said, but chemists can tinker and cook up new forms of synthetic drugs “in a weekend” to dodge existing regulations.

Some people end up mixing drugs unwittingly, as fentanyl and unexpected additives turn up in cocaine, methamphetamine and counterfeit pills. Others choose to intentionally mingle drugs for their combined effects.

Dr. Daniel Ciccarone, a UCSF professor of addiction medicine, said that in the past, many drug users disliked mixing heroin and meth because the stimulant “bowls everything else out of the way,” overwhelming the effects of the heroin. But with fentanyl, he said, “I think methamphetamine has met its match.”

“You’re talking about two very powerful drugs, going mano a mano,” Ciccarone said. “And it’s worrisome in terms of what it’s doing physiologically.”

Fentanyl, heroin and other opioids can be deadly because they suppress breathing. Adding in synthetic benzodiazepines can ramp up the risk that someone stops breathing because benzodiazepines — a category of drugs that includes prescription medications like Xanax or Valium used for anxiety — are sedating drugs that increase drowsiness and decrease respiration. Methamphetamine, in turn, can disrupt the electrical signals in the heart, fatally knocking off its rhythm, said Dr. Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

If you combine meth with opioids that hinder breathing, “you can see why this would be a very, very lethal combination,” Volkow said.

Friedman, the UCLA addiction researcher, said that as drugs have gone synthetic, “there are different kinds of opioids, benzodiazepines, stimulants and cannabinoids being synthesized and invented and mixed into the drug supply all over the place — and for the most part we don’t know about them.”

One of the lesser-known drugs he has tracked is xylazine, a veterinary tranquilizer that has popped up in Philadelphia and the East Coast as an additive to lengthen the effects of fentanyl.

Xylazine, which has been linked to gruesome wounds, has not been identified as a major issue in California, but without testing, “we don’t know whether or not that’s circulating here,” said Steffanie Strathdee, a UCSD professor in its department of medicine. “We ask people what they’re using in our ongoing study, but if they don’t know what they’re using, then it’s pointless.”

In North Carolina, Dasgupta has been partnering with a community group in Greensboro that analyzes the content of drugs using a technique called FTIR — Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy — with a machine roughly “the size of a toaster oven.”

He and other researchers built on that work to launch a program that allows drug samples to be mailed in and analyzed from across the country, using a kit that Dasgupta likens to a COVID-19 test, with a swab and a vial of organic solvent that makes the drug sample “unusable” in the eyes of federal authorities.

The amount needed is tiny — “literally a pinhead,” Dasgupta said — which a university lab analyzes with a sophisticated instrument called a gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer. Dasgupta said he has been studying heroin for decades, but the resulting data has startled him with its sheer variability.

Someone can purchase a drug from “the same dealer, the same day, the same block” — even with the same stamp as a form of branding — “and it can be completely different,” he said.

Across the country, such drug checking has often been inhibited by laws prohibiting drug paraphernalia, which differ dramatically from state to state and can be written “extremely broadly,” said Corey Davis, director of the Harm Reduction Legal Project. Some states have begun to expressly decriminalize fentanyl testing strips; North Carolina has a law allowing “drug testing equipment.”

California law says that people operating syringe programs — and program participants — are not supposed to be prosecuted for having or handing out things that have been deemed necessary by state or local health departments to prevent overdoses.

The California Department of Public Health has named fentanyl test strips as one of those necessary tools; it has not specifically designated FTIR machines or their analysis that way, although it “has begun a review of public health literature examining its efficacy as an overdose prevention strategy,” the department said.

Cost can also be a barrier to moving beyond test strips for community programs that often run on skimpy budgets. In North Carolina, the FTIR and associated supplies cost around $45,000; the high-resolution instrument at the university lab can run upwards of $600,000, according to UNC research chemist Erin Tracy.

In San Diego, UCSD researchers have been working with the Harm Reduction Coalition of San Diego and other partners to develop a new program that will run drug samples through an FTIR machine, producing a rundown detailing their drug makeup in 15 minutes.

It could yield much more information than the $119 test kit that Stamos-Buesig has been buying and using, which includes nine reagents to check for specific drugs and substances, but cannot detect new adulterants that are not responsive to those chemicals, nor gauge how much of each drug is in a sample.

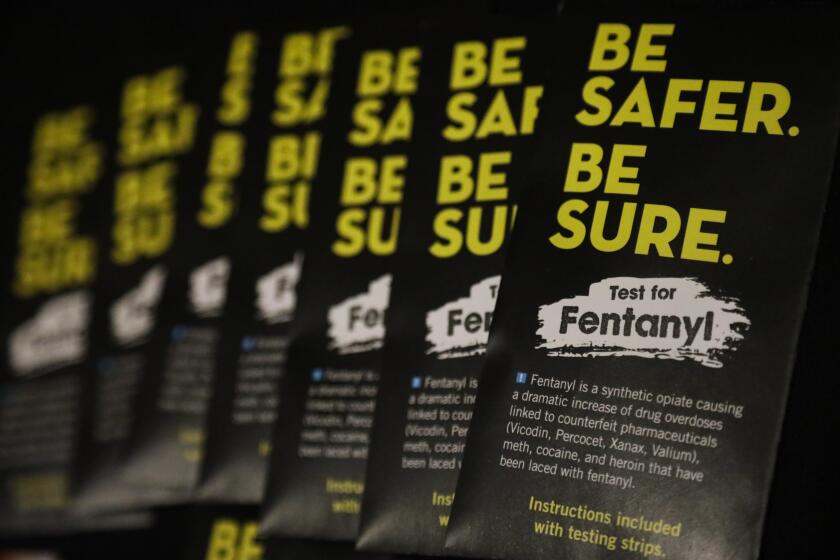

Fentanyl is often mixed with other drugs (including heroin, methamphetamine and cocaine) to increase potency, but it can be deadly. Test kits can help.

At one point, Billy landed in the hospital because “there was something in the crystal — something they cut it with — that he was allergic to,” his girlfriend said. Stamos-Buesig checked a sample after Billy was hospitalized, but couldn’t pin down what was different about it, since it didn’t respond to the reagents in her kit.

The planned program in San Diego, which is expected to launch this fall, will have two aims: People will be able to find out what their own drugs contain, and the public will be able to track what is in the broader supply through an online dashboard.

“If you were somebody who used heroin in Chula Vista, and you were worried about the extent to which it might be contaminated with fentanyl, you’d be able to zero in on that region and see what the trends are,” Strathdee said. Alerts would go out “if there’s a new drug on the scene or if there’s a dangerous adulterant.”

The machine, which costs approximately $45,000, is being funded by a foundation named for Josh Gaffen, a UC Berkeley graduate who loved cars, science fiction and fishing and who died at the age of 39 from a fentanyl overdose. His sister Shayna Gaffen said her family thinks often about how his death could have been prevented.

“The goal of harm reduction is to meet drug users where they are,” Gaffen said, “so they can live long enough to start to imagine a different reality.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.