‘We were robbed’: Norman Mineta’s long quest for justice for Japanese Americans

- Share via

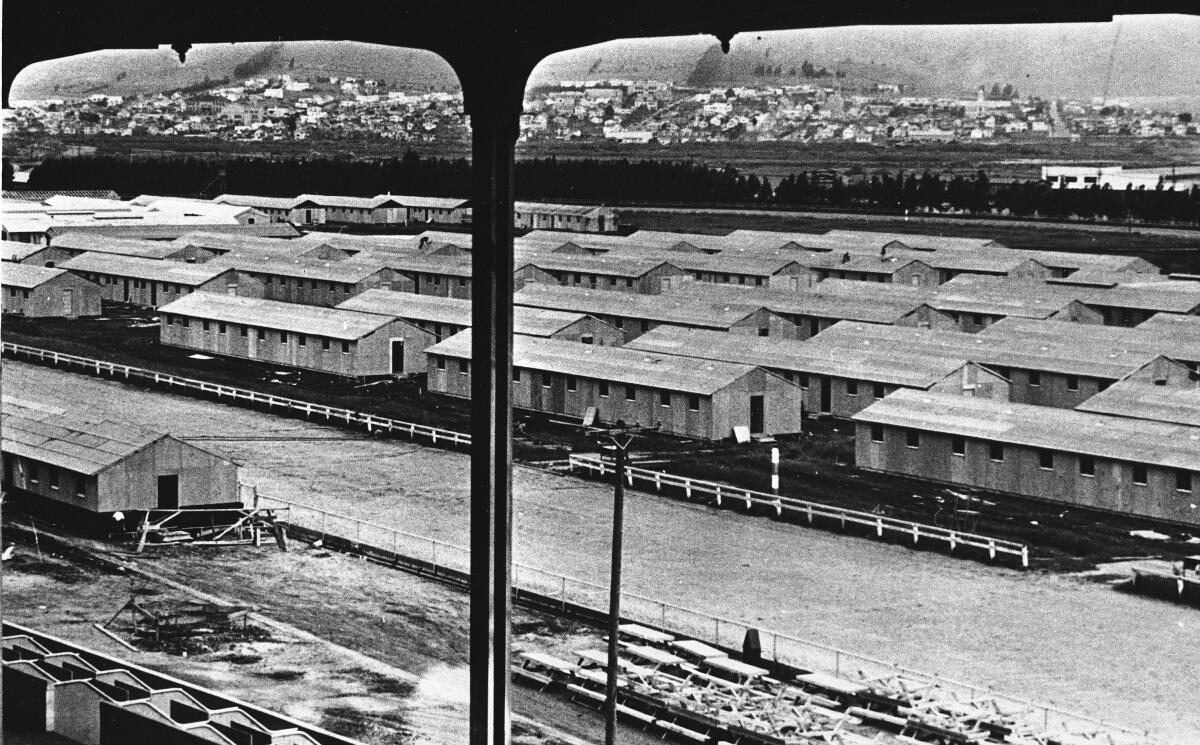

Norman Mineta was 10 years old when he and his family were taken in 1942 from their home in San Jose to a prison camp established at the Santa Anita racetrack.

He was one of 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry who were ordered to the World War II camps. Mineta, who died Tuesday at age 90, went on to become a powerful congressman from San Jose and serve in the cabinets of two presidents.

But perhaps his greatest legacy was his long fight to win congressional approval of legislation — later signed in 1988 by then-President Reagan — expressing a national apology and providing a $20,000 tax-free payment to every survivor of the incarceration camps.

Here’s a look at his efforts from the pages of The Times:

Incarceration

All persons of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast were rounded up and sent to one of 10 incarceration camps in the western United States and Arkansas under a 1942 executive order signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Despite arguments that the order violated the constitutional rights of those sent to the camps without any charge or trial, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1944 the action was within the president’s powers as commander-in-chief in wartime.

In 1980, a special commission was created to examine the issue. It recommended that compensation be paid, concluding that the mass incarceration was based on war hysteria and racial prejudice. No similar action was taken against Americans of German or Italian ancestry, although the United States also was at war with those two countries.

Mineta frequently spoke of his family’s experiences in the camp, which started with the 345-mile train ride from his home in San Jose to a temporary assembly center at the Santa Anita racetrack.

“We were fortunate because ... we were not in the horse stables,” Mineta said. “We were in barracks ... that had been built. I remember going to visit friends ... in the horse stables during the hot months of the summer. They might have swept out the horse stables, but the stench was still there. How, frankly, they lived in those, I’ll never understand.”

Fight for justice

Mineta — along with three other Japanese American congressional leaders: Robert T. Matsui, Daniel K. Inouye and Spark M. Matsunaga — proposed that the redress campaign first start with a national commission to investigate the factors that led to the incarceration. Some Japanese American activists disagreed, saying the process would take too long and pressed instead for legislation to directly award compensation, but Mineta and others argued that a commission process would be more politically effective to ultimately win reparations.

At first, there was major opposition in Congress, with one Republican congressman from California worrying it would swell the deficit and open the door for reparations for Native Americans.

Mineta rejected the critics forcefully. “We were robbed,” he said in 1986, “just as if agents of the government had crept into our homes at night and taken our liberty, our rights and our property. There is no statute of limitations on our shame, our damaged honor or our violated rights. It has fallen on this (Congress) to set us free.”

The day Congress passed the bill, he spoke about the history being made. “This legislation touches all of us because it goes to the very core of our nation,” Mineta said. “I am deeply honored to serve in this body as it takes the great step of admitting and redressing a monumental injustice.”

The bill, whose total price tag was $1.25 billion, passed by a vote of 257 to 156.

“This was a day of reckoning for the House on the issue of redress,” Matsui, a Democrat from Sacramento, said at the time. “I consider the outcome a major victory not only for those who were interned but for the country. It’s clear now that Congress has lived up to its moral obligation.”

A legacy

In 1988, Reagan signed the bill into law. “We gather here today to right a grave wrong,” said Reagan, citing the hardships endured by Mineta.

“No payment can make up for those lost years,” Reagan said. “So what is important in this bill has less to do with property than with honor, for here, we admit a wrong. Here we reaffirm our commitment as a nation to equal justice under the law.”

A year later, the first payments went out.

“In the annals of civilization, there aren’t many instances of a government apologizing this way,” Mineta said. “Here we have a government saying, ‘We were wrong, we apologize.’ It’s just exhilarating to see these things happening.”

Further reading:

Reparations: Groups from L.A. will lobby Washington on behalf of Japanese Latin Americans and fired rail and mine workers.

The House, with Rep. Norman Y.

When a top Justice Department official presents a letter of apology from President Bush and separate $20,000 checks Tuesday to six Japanese-Americans who were forcibly interned during World War II, there will be no grand entrances and exits.

Sumi Seo Seki remembers entering the expansive grandstands of Santa Anita in Arcadia, with their magnificent view of the San Gabriel Mountains.

It was the early 1940s and Aiko Yoshinaga’s world seemed secure: After graduating from Los Angeles High School and spending summer vacation with friends, she would attend secretarial school in the fall.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.