Column: At Tom Rivera’s memorial service, his dream of ‘Future Leaders’ is fulfilled

Outside San Salvador Church in Colton, a guitar trio played the bolero classic “Sin Ti” (“Without You”), accented by horns and bells from passing trains.

As mourners entered, they wrote tributes to the man they called “Dr. Tom” and stuck them in a box, which quickly overflowed.

Tom Rivera grew up two blocks away in a barrio on the south side of the railroad tracks that bisect the city.

On a sweltering Friday afternoon last month, he was remembered in the low-slung church crowned with four white crosses and Aztec geometric motifs.

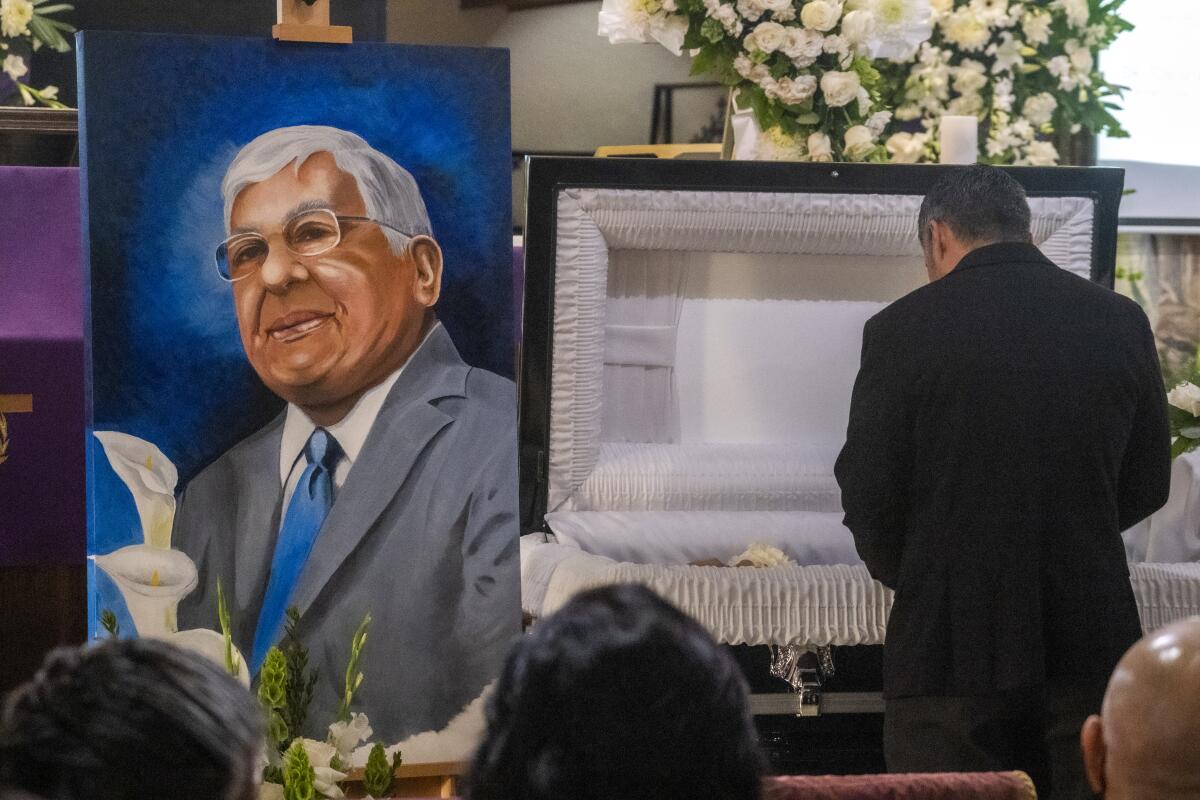

Beside Rivera’s coffin, where he lay in a UCLA robe and sash, was a painting of him holding a lily and a photo of him in the wheelchair he had used for four decades.

They were lawyers, teachers, doctors, politicians. They were there to remember their mentor, who died of cancer at 82. They were also there to celebrate themselves.

After all, many of the hundreds of people who sat in San Salvador’s worn-out chairs were his life’s work. They had once been Latino kids who needed a dose of self-confidence and optimism to succeed.

Judith Segura-Mora, Future Leaders class of 1985, approached the lectern.

**

The son of an orange picker, Rivera grew up in a wooden house built from the planks of old boxcars.

In the Colton of his childhood, the Southern Pacific and citrus industry were kings yet forced their Mexican workforces to live as second-class citizens. Students received subpar education in segregated schools. Mexicans couldn’t step in the white part of town after sunset.

The inequities even played out in the religious sphere. When Catholic leaders built a new church, they placed the towering Immaculate Conception in north Colton, even though San Salvador’s parish community dated from the 1890s.

“That experience molded him,” said his daughter, Evelyn Rivera Molina. “He felt it was just something wrong with that. It created a little fire inside of him to make it right.”

He did things no Mexican kid from South Colton was ever supposed to do. He went to Colombia in the early 1960s as a Peace Corps volunteer. He earned a doctorate in education from UCLA, working afterward as a sixth-grade teacher, a community college counselor and a university administrator — whatever it took to better the prospects of young Latinos in the Inland Empire.

With his wife, Lily, Rivera raised money for college scholarships. In 1978, he won a seat on the Colton school board. In his spare time, the short but strong Rivera became a champion handball player.

Then one day in the summer of 1981, he woke up unable to move his arms and legs.

Guillain-Barré syndrome, doctors said — an autoimmune disease with no known cure.

Most patients recover enough to walk again, but Rivera, a father of three young children, was left a paraplegic.

“When is this going to be over with?” the San Bernardino Sun quoted him as saying in 1982, a couple of months after he returned home from a yearlong hospital stay.

But he eventually regrouped — and redoubled his efforts to help young Latinos.

“He was impossibly positive,” Lily, his wife of 56 years, said recently. “He couldn’t see clouds. He couldn’t see storms. Any problem that came up, for most of us, we’d say, ‘No, we can’t do that.’ He’d say, ‘Let’s find out.’”

Rivera went back to his job at Cal State San Bernardino. In 1985, he and other educators created Inland Empire Future Leaders. Every summer, hundreds of Latino eighth- and ninth-graders from Riverside and San Bernardino counties gathered for a weeklong camp in the piney woods of Idyllwild.

Rivera and other adults let the teens be teens — singalongs, outdoor activities, silly icebreakers — while challenging them to not become a statistic. Go to college. Succeed in life. Come back home. Give back.

I first met Rivera more than a decade ago, when he invited me to speak about my job at a Future Leaders camp. I had never heard of him or his organization, so I wasn’t sure what to expect as I made the winding trek from Orange County to the heights of the San Jacinto Mountains.

The wheelchair was the first thing I noticed, but I quickly forgot about it once I saw his smile.

It was a broad, bright grin that never dimmed, one that transformed every room he entered and fueled his frequently funny, always inspiring speeches to children and adults alike.

It’s what came into my mind whenever Rivera sent an email to congratulate me at various points in my career — a new book here, a promotion there. I was one of many local Latinos whose accomplishments he tracked and marked, showing that he noticed, and he cared.

In my many years covering Latinos in Southern California, I’ve never met someone so quietly influential as Dr. Tom. He was the epitome of the old journalism adage “Show, don’t tell.” Whenever I’d meet another Latino mover and shaker from the Inland Empire, they’d inevitably be a Future Leader alum, and I’d ask how Dr. Tom was doing.

Planning for the next Future Leaders, they’d always say — and was I going to speak this year?

**

“Even in death, Dr. Tom Rivera did what he did best in life — brought people together,” Segura-Mora told the crowd in San Salvador Church, about half of whom were Future Leaders alums.

Although Rivera’s passing was sad, he wouldn’t have wanted anyone to feel bad this evening, she said. “He’d want us to make sure to take that vitamin S” — a smile.

And with that, the latest Future Leaders camp was underway.

“His quixotic optimism unifies us all,” said Riverside County Deputy Dist. Atty. Carlos Monagas, class of ’85 and co-emcee of the memorial along with Segura-Mora. In the crowd was Monagas’ niece, a graduate of last year’s Future Leaders virtual summit.

Rudy Monterrosa (1988), a lawyer in South Bend, Ind., and a former member of the school board there, led a unity clap — the traditional activist applause that starts slow and ends in a thunderous crescendo.

R.C. Heredia (1992), current Future Leaders board chair, Colton native and psychology professor at East Los Angeles College, thanked Rivera for teaching him that “giving back to your community is one of the greatest gifts you could offer.”

There were inside-baseball camp references to “cariño grams” and “familia” that drew knowing nods.

When another speaker urged everyone to stand up and engage in a favorite Rivera exercise — point your thumbs at yourself and shout, “ I am! Somebody!” — no one rolled their eyes at the earnestness. They had done it as kids, and they were more than happy to do it again as adults.

A recording of Dr. Tom played over one slide show.

“I feel that a person needs to feel good about themselves,” he said. “They need to feel that people will listen to them. They need to feel that people will help them. And I think that’s the first thing that people need to become empowered.”

In one of Rivera’s most visible triumphs, two of the Inland Empire’s congressional districts are represented by Future Leaders alums — Pete Aguilar (1993), a fourth-generation resident of the area, and Raul Ruiz (1989), the son of immigrant farmworkers and a graduate of Harvard Medical School.

The congressmen flew back home from D.C. to attend the memorial, then got stuck in Friday night traffic. They sent recorded messages to play to the crowd — Aguilar finally showed up near the end.

Others spoke of Rivera’s influence outside Future Leaders.

Dr. William Keh, board director for the Tzu Chi Medical Foundation, told the crowd how the Buddhist organization sought out Rivera in the early 1990s to help establish free health services in San Bernardino because they respected his sunny, do-the-hard-work approach.

California Assembly Majority Leader Eloise Gomez Reyes (D-Grand Terrace) proudly joked that Rivera “always claimed” their hometown of Colton wherever he went.

Gomez Reyes, an attorney, recalled that she asked Rivera to talk to one of her clients, a 16-year-old named George who became a quadriplegic after being shot.

Rivera was blunt with George about how society would view him — they’d just notice the wheelchair.

“But if you smile,” she recalled Rivera saying, “the first thing they’re going to notice is your smile.”

Two decades after that meeting, “George still remembers what Tom told him. And he smiles.”

The grand finale was a slide show Rivera created in anticipation of when his body would fail.

With Whitney Houston’s “One Moment in Time” as a soundtrack, flashes of a life well-lived passed by. Photos of a happy childhood. College graduation portraits. Vacation snapshots with his family. The time he met President Clinton. Scenes from the hospital stay that changed everything, and yet nothing. Image after image of Future Leaders camps through the decades.

People laughed. People sighed. People wept. After it ended, they stayed around and caught up.

Rivera would be buried the following day. Another reunion would happen.

Then, they would disperse across the region and the country, back to their jobs educating, legislating, healing, advocating — leaders, all.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.