After ‘Real Housewives’ scandal, scathing audit says California fails to stop corrupt lawyers

- Share via

The State Bar of California has failed to effectively discipline corrupt attorneys, allowing lawyers to repeatedly violate professional standards and harm members of the public, according to a long-awaited audit of the agency released Thursday.

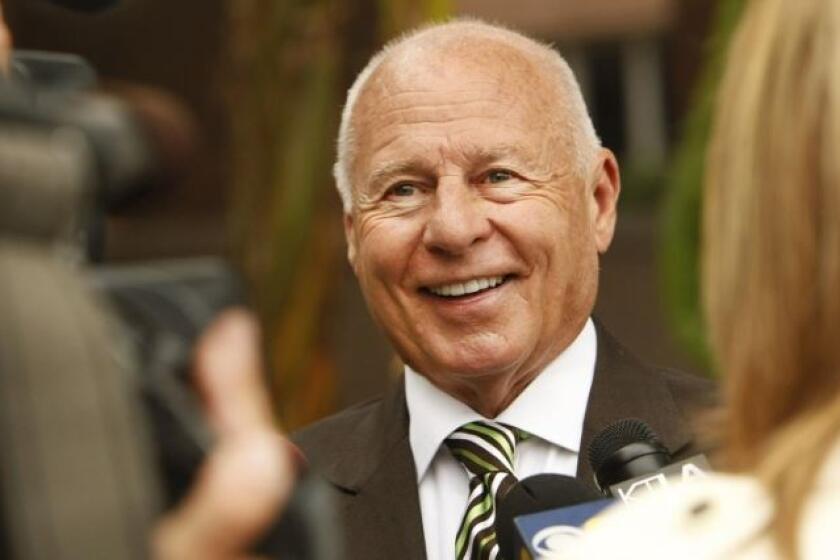

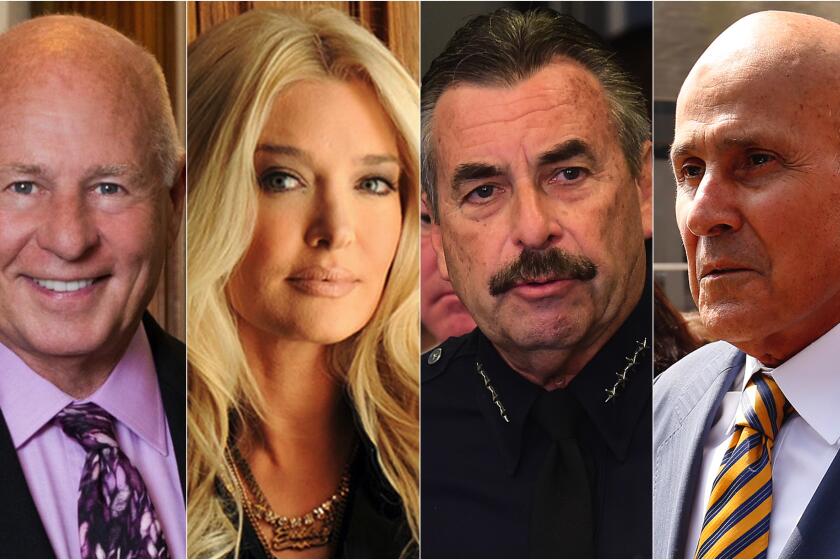

The audit of the State Bar was ordered last year by the Legislature in the wake of a Los Angeles Times investigation that documented how the now-disgraced attorney Tom Girardi cultivated close relationships with the agency and kept an unblemished law license despite over 100 lawsuits against him or his firm — with many alleging misappropriation of client money.

After the State Bar acknowledged its “mistakes” in handling complaints against Girardi that spanned four decades, the Legislature mandated the public examination of the attorney discipline system.

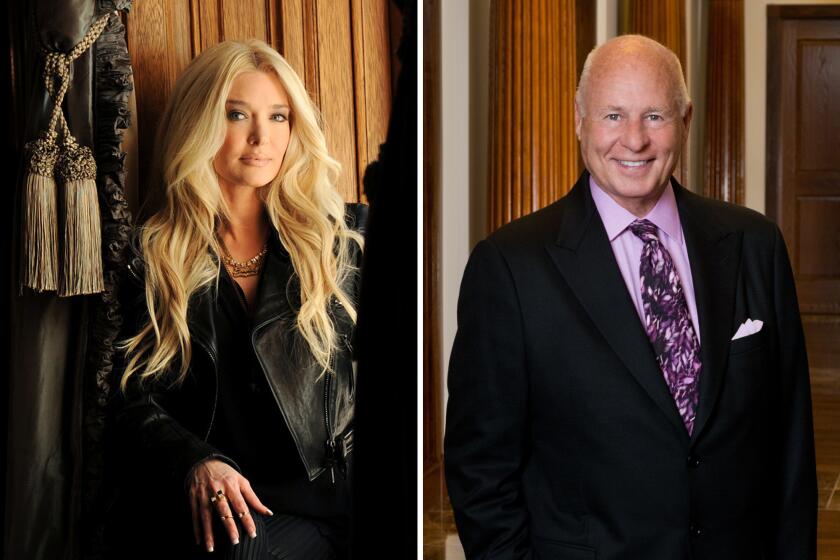

Tom Girardi is facing the collapse of everything he holds dear: his law firm, marriage to Erika Girardi, and reputation as a champion for the downtrodden.

The audit concluded that the State Bar failed to properly investigate some attorneys even as complaints poured in, relied on confidential warning letters and other nonpublic methods that did little to deter misconduct, and has not dealt with the conflicts of interest between its regulatory staff and the attorneys whom the agency is tasked with policing.

“These are fundamental breakdowns,” acting California State Auditor Michael Tilden said in an interview. “The State Bar has a lot of room to improve their policies to better protect the public from attorney misconduct.”

Tom Girardi and his firm were sued more than a hundred times between the 1980s and last year, with at least half of those cases asserting misconduct in his law practice. Yet, Girardi’s record with the State Bar of California remained pristine.

A team of auditors pored over the State Bar’s internal data and identified examples of specific lawyers with disturbing track records who received little or no discipline. None of the attorneys were named in the report. One was the subject of 165 complaints over seven years, but auditors found that many of the complaints were dismissed outright or closed after the bar issued private letters to the lawyer.

“Although the volume of complaints against the attorney has increased over time, the State Bar has imposed no discipline, and the attorney maintains an active license,” Tilden said in a letter summarizing his office’s findings.

While working as a watchdog for the public, Tom Layton spent hours advancing the interests and political connections of one lawyer with a long record of misconduct complaints, emails obtained by The Times show.

Another unidentified attorney had been the subject of several complaints alleging a failure to give clients money from their settlements. “When the State Bar finally examined the attorney’s bank records, it found that the attorney had misappropriated nearly $41,000 from several clients,” Tilden wrote.

The chair of the State Bar’s board of trustees, Ruben Duran, said in an interview that he was troubled by the audit’s findings, calling its conclusions “some of the hardest-hitting discoveries” that the State Auditor has ever made about the agency. He said that staff and leadership wanted to ensure the public was better protected, and that many reforms had been implemented after the Girardi case exposed deficiencies.

“It shouldn’t matter whether your lawyer is an A-list celebrity or a solo practitioner down the street. Everyone deserves competent, ethical legal services,” Duran said. He noted that the State Bar went about two decades without fee increases, and said some of the problems at the bar stem from this long-term underfunding at an agency that has to monitor more than 250,000 attorneys.

Duran noted that the bar had implemented reforms that address some of the issues highlighted by the audit, including proposing a new program to monitor attorney trust accounts, increased oversight of the chief trial counsel’s office, and twice yearly reviews of closed cases by an outside auditor. Last summer, the agency also hired George Cardona, a former federal prosecutor, to serve as chief trial counsel.

But fully implementing the State Auditor’s recommendations would require about 30 new employees and $1 million in one-time funds, Duran said.

Assemblymember Mark Stone (D-Scotts Valley), who is chair of the Assembly’s Judiciary Committee, said the audit was “profoundly eye-opening.”

“Victims of unscrupulous lawyers should not be re-victimized by a State Bar that too often has protected those lawyers from full scrutiny,” Stone said in a statement. “We will continue to push the Bar to get back to basics and reform its discipline system once and for all.”

Girardi was once a top plaintiffs’ attorney and Democratic powerbroker who gained reality TV fame on “Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” alongside his third wife, Erika. His downfall in December 2020 was in part triggered by a judge finding that he had misappropriated millions from families of those killed in an Indonesian plane crash. But after the collapse of his Wilshire Boulevard law firm, scores of clients came forward saying they were swindled by Girardi and The Times documented a trail of misconduct allegations going back decades.

Earlier this month, a Chicago law firm accused Girardi and other lawyers at his defunct firm of running “the largest criminal racketeering enterprise in the history of plaintiffs’ law,” pocketing millions from clients, vendors and fellow attorneys.

That Girardi’s serial misconduct went unchecked for decades has forced a reckoning among the legal establishment. In addition to the State Bar’s acknowledgement of past mistakes, the agency has also been conducting a broad investigation into whether its own employees or other agency insiders helped Girardi skirt scrutiny. That investigation is ongoing, Duran confirmed.

Girardi is not named in Thursday’s report by the State Auditor, but the findings make clear that he was not alone in sidestepping sanction by the bar’s disciplinary system.

“I think we definitely identified misconduct that does impact the average Californian if they are using the legal system,” said Jon Kline, a principal at the auditor’s office who helped lead the review. “Misappropriation is a concern: That’s money that should be going to clients that the attorney has absconded with.”

The audit found that the State Bar failed to fully identify patterns of misconduct and investigate further, either because of its case management system or because of how it treats complaints that are withdrawn. For example, one attorney was named in multiple complaints for failing to pay settlement funds. The bar closed each after the attorney “finally paid the client,” but the audit states that the bar did not obtain the lawyer’s bank records until it received more than 10 complaints over two years.

“When the State Bar finally examined the client trust account, it found that the attorney had misappropriated nearly $41,000 in total from several clients,” the audit states.

The audit found that the State Bar had also prematurely closed cases that needed further investigation or potential discipline, often through a host of confidential methods, like issuing private warning letters that are not knowable to the public. The audit found inconsistencies in the use of nonpublic methods, and indicated the agency had relied too much on such secretive forms of discipline.

From 2010 to 2021, the bar used confidential letters or warnings to attorneys twice as often as it sought public discipline. During that time frame, more than 700 attorneys had at least four or more complaints each that were closed through private measures. The auditors reviewed five attorneys’ cases and found the cases were closed “despite indications in its case files that further investigation or actual discipline may have been warranted.”

The State Bar had only one outside reviewer, and that person had been the sole person examining closed cases since 2012. The State Bar’s staff was also selecting which cases the reviewer examined, and the reviewer’s findings went to management, not its board of trustees.

“Anytime findings are going through management, it introduces the risk that what is provided ultimately to the governing body is altered,” said Kline, the principal auditor.

Other errors were basic investigatory lapses, like accepting poor levels of evidence. An attorney who had overdrawn a client trust account twice in a month was asked by the bar to provide bank records. The attorney turned over bank statements but left out the month when the trust account was overdrawn. Instead, the lawyer provided a narrative of transactions in that month. Rather than request the bank statement, the State Bar accepted the lawyer’s explanation and closed the case.

Kline declined to specify what was behind the reliance on weak evidence, but said: “There is this focus on closing cases quickly in order to keep the backlog under the control.”

Prior audits and other officials had previously criticized the bar for a crippling backlog, or cases that go six months without any action by the agency.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.