Column: A stabbing at a Long Beach liquor store sparks memories of the L.A. riots

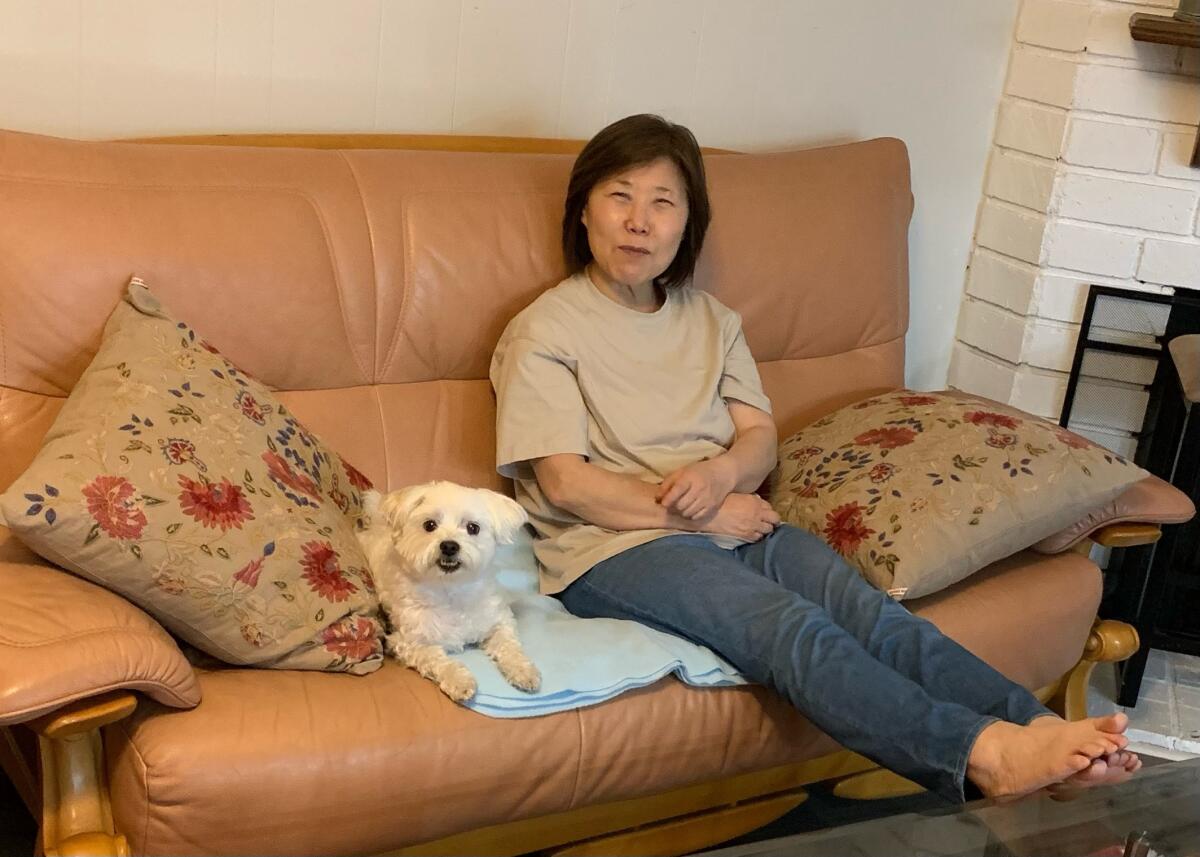

Yongja Lee, 65, and her husband were on the verge of retirement when she was stabbed at their liquor store in Long Beach on Jan. 30.

Closed-circuit camera footage shows the attacker, a 6-foot tall Black man in a red Adidas sweatshirt, walking up to Lee, who has her hands raised protectively. After a brief exchange the man stabbed her at the base of the neck before striding away.

For the record:

4:45 p.m. March 7, 2022An earlier version of this report said police released a photo of the victim in the stabbing. They released a photo of the suspect.

It was not an especially unusual crime for downtown Long Beach, which experiences higher rates of violence than surrounding neighborhoods. After a month, police have arrested no suspects. They released a photo of the suspect on Friday, which is not an especially slow pace for an investigation.

“We’re investigating the crime like we do all the others,” said Richard Mejia, a spokesman for the Long Beach Police Department. Detectives are not currently treating it as a hate crime, he added.

But with the recent pandemic-related violence against Asian people, the crime made waves in the Korean American community. And this year is the 30th anniversary of the L.A. riots. For some Korean Americans, violence at a liquor store, especially between Black and Korean people, awakens painful memories.

Long Beach police say they’ve been getting calls about the case from Korean-language media inside and outside the United States. Chosun Daily, a Korean-language newspaper, had been pushing authorities to release the photo. On Friday, the newspaper issued a statement about the case.

“All victims should be treated and considered same from a media or police investigation without a racial and social level after a crime happened,” it wrote. “Any victims shouldn’t be left over because of their social position in terms of stimulating subscribers or fall behind in police investigation.”

Lee, whose spinal cord was injured in the attack, is paralyzed from the neck down and can no longer speak. She will need long-term care, and the family’s only way to finance that is applying for Medi-Cal.

“I am an only child,” said Ellyn, Lee’s daughter. “She’s like my best friend. It just hurts so much. Now I have to read her lips.”

The timing of the attack couldn’t have been worse. After decades of no days off or vacations and 14-hour days, Lee and her husband had just found a buyer for the store. They were waiting for paperwork to come through when the attack happened.

Lee and her family did not experience the Los Angeles riots. They came to the United States in 2000. They ran a movie rental store in La Puente, and when streaming services made their business obsolete, they ended up at Frank’s Liquor in Long Beach. They worked so much, Ellyn says, that the family does not have a photo of them all together, because they never had time.

Ellyn did not become aware of the riots until after college, when she encountered some blog posts and news articles. She doesn’t know all the details, but she understands that Korean Americans were scapegoated.

“I learned how the media played things up to make the Korean and Black community fight each other, even though it was the government and Police Department’s fault,” she said.

Ellyn doesn’t think that the racial conflicts of the riots had anything to do with her mom’s stabbing. Customers at the store — largely Black and Mexican — loved her mom. Lee would make kimchi jjigae for dinner in the store and share it with the neighbors above. When they heard the news of her attack, supportive customers flocked to the store. One customer started a GoFundMe and raised nearly $10,000.

“This time it’s not the community against us. The community is actually for us, and is trying to raise attention for us,” Ellyn said.

The riots may be distant history for Ellyn, but racism is something she has become intimately familiar with since she arrived in the U.S. as a teenager. At school, classmates would bully her and throw trash at her for being Asian. She observed how hostile customers act toward service staff who don’t speak English. After the pandemic brought a wave of anti-Asian violence, Ellyn saw the importance of speaking out publicly about it.

“Now we are all getting targeted, and all Asians are realizing how important it is to make a louder voice,” she said.

And Ellyn expected more from the Police Department, even if she understands that non-murder cases are a lower priority. She says the Police Department was unaware of the extent of her mother’s injury. And after soliciting security footage from the store in January, the detective on the case had not contacted them once, she said.

“Just because my mom didn’t die,” she said, “that means we can’t get justice?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.