Body of war hero left for 10 days in morgue, state investigation finds

- Share via

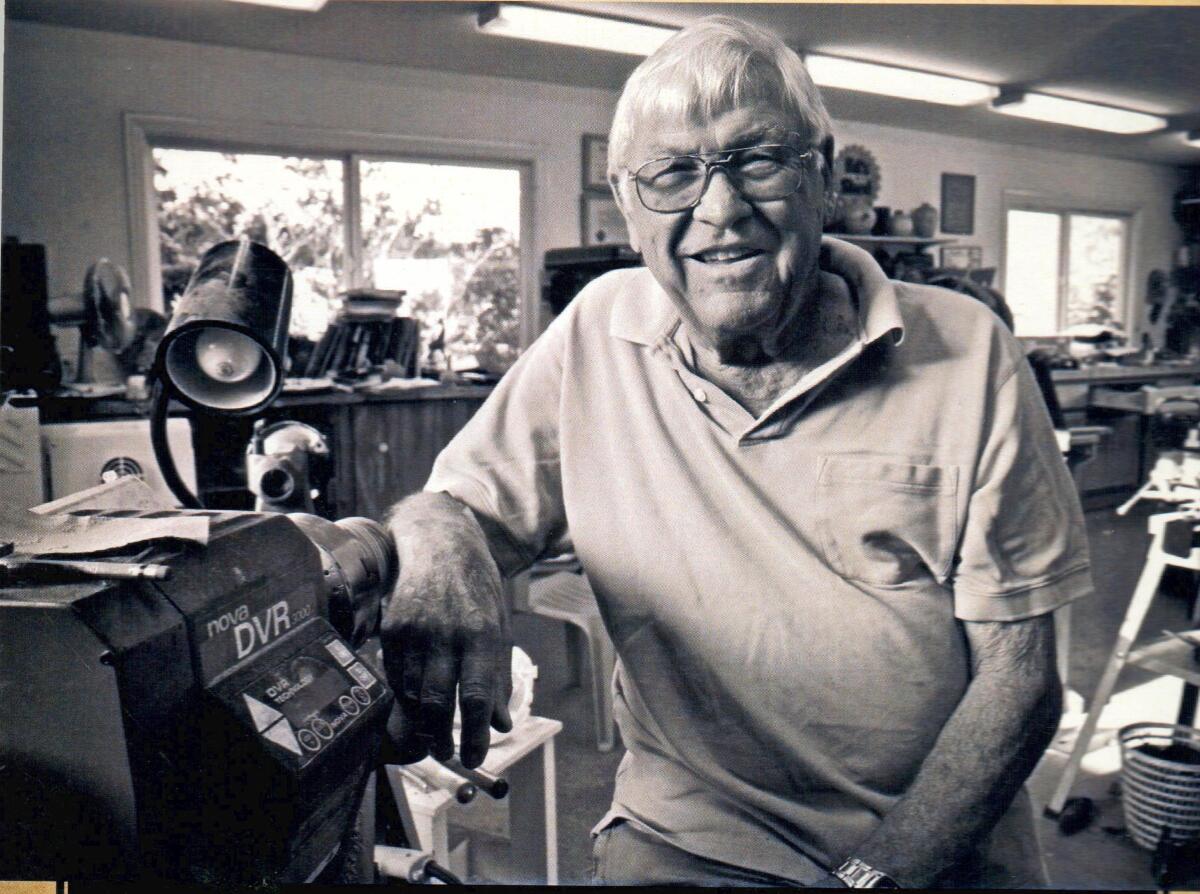

Long before he died at Palomar Medical Center in Escondido, Calif., last year, Edward Anderson was a decorated World War II hero.

He was awarded both a Bronze Star and the Distinguished Service Cross, the Army’s second-highest honor and a tribute reserved for those soldiers who display extraordinary heroism.

Anderson was just shy of 95 when, in April 2020, he arrived prepared at Palomar Health. He and his family gave the medical staff explicit directions on what to do with his remains if he did not survive, the family said.

Three days later, on April 14, the former Army private, retired veterinarian and patriarch of a northern San Diego County family died.

Instead of contacting the crematorium Anderson had a pre-signed agreement with, Palomar medical staff wheeled his body into the hospital’s morgue, where it languished for 10 days, until a security guard figured out something was wrong and called the mortuary, a state investigation found.

The Anderson family complained and the subsequent state investigation revealed a number of problems with the morgue, including that in 2020 several other bodies had been left at least eight days or longer in the morgue, including one for 27 days.

According to the state investigation completed in June, the morgue’s processes were not fully developed, its staff was not properly trained, and there was no morgue log or regular tracking of how long bodies were stored.

“There was no monitoring of the length of time decedents remained in the morgue and there was no monitoring of the morgue log records,” the California Department of Public Health report from June 30, 2021 states.

“As a result, there were delays and errors in processing the remains of a patient when the patient’s body remained in the morgue 10 days post-mortem without family or mortuary notification,” it said.

The man collecting the Loma Linda hospital’s COVID victims was all but invisible

Palomar Health, a public hospital district that serves northern San Diego County with more than 3,000 employees and a $4.5-billion budget, said in a statement that it has taken actions to improve its morgue.

“In the case of Mr. Anderson, we regretfully had a miscommunication with the family, which caused a delay in the transportation of his body to the mortuary,” the statement said.

“In the ensuing investigation, we identified training and policy shortcomings and have since taken corrective action to ensure our training and practices match our commitment to provide every patient and family world-class treatment,” it added.

The hospital now designates a specific liaison to work directly with families when someone dies to make sure everyone understands the process, the statement said.

“We take caring for the deceased very seriously, providing a secure, dignified, climate-controlled environment until transportation is arranged to the mortuary,” the statement concluded.

Palomar Health submitted a corrective action plan to the state but declined to release a copy to the San Diego Union-Tribune. Under hospital policy, a spokesman said, the request for the document must go through a legal review that would take at least two weeks, in case elements of the plan need to be redacted for confidentiality reasons.

Carole Anderson Lucia, one of Anderson’s five daughters, said she remains angry at how the hospital handled her father — and her formal complaint to administrators last year.

No one should be treated the way her dad and family were by Palomar Health, Lucia said.

“Every patient, living or deceased, has basic rights to dignity and care, and they failed miserably,” she said. “Not just with my father but with so many patients before him. And they were so flippant and callous about it.”

The 14-page findings from state Department of Public Health investigators show that regulators took the Anderson family’s complaints seriously.

The completed report notes that the department’s Licensing and Certification office conducted an unannounced site visit on May 20, 2020, about five weeks after Anderson died.

Over the last 15 months, 52 unclaimed bodies of U.S. military veterans accumulated at the Los Angeles County morgue because nobody arranged transportation to Riverside National Cemetery for burial.

The investigators interviewed Palomar Health staffers as well as the crematory manager over the following weeks and months, the report shows. More than a year later, the Anderson family’s allegations were substantiated by state investigators.

Among other findings, licensing officials noted the hospital had no checklist for nurses to refer to when handling the deceased. Also, there was no place in the clinical record to document when a mortuary had been contacted or when a body was picked up.

“The DSS (director of social services) stated, ‘There is confusion as to who calls the mortuary, no documentation required and no place to document it. Unable to prove anyone was notified or when. It is not the facility practice to contact the mortuary,’” the investigators said.

Investigators also said the director of social services informed them that a nurse “failed to provide Patient 1’s family the brochure, which directed them to contact the mortuary to pick up Patient 1’s body.”

The director and another Palomar Health administrator acknowledged to investigators that neither the brochure nor hospital policy directed family members to contact a mortuary.

“We need to firm up the process notification and pick up,” a hospital director said.

State investigators examined the daily morgue census over an 11-day period in April 2020 and found a full day of records missing.

“The DSS stated she may have deleted it,” the report states.

In July 2020, investigators interviewed the Palomar Health administrator on call, who spoke with Anderson’s widow.

The administrator on call “stated Patient 1’s wife was very upset,” the report said. “There was a lot of pain, very distraught, it was a hard conversation.”

In August 2020, investigators examined Palomar Health morgue records between the prior January and April. They found 13 cases where information regarding the dates and times that decedents were moved was missing or blank.

One of those cases involved a deceased baby who left the morgue on March 27, but there was no record of when the baby arrived or which staffers were involved.

In 10 cases, the mortuary entry was missing, investigators said.

The hospital’s lead security officer “stated the information on the logbook was important and should have been completed,” the state report said.

Also in August 2020, investigators reviewed morgue records between Feb. 20 and March 20. They found four instances in which decedents had remained in the morgue for eight days or longer, including one who was stored for 27 days.

A hospital administrator “stated she was not aware of the reason for this length of time the decedents remained in the morgue (and) also stated the facility did not document reasons decedents remained in the morgue,” the report said.

By Aug. 19, 2020, Palomar Health had submitted a ”quality assurance improvement plan” to state regulators, but “the plan did not include any morgue services monitoring,” investigators wrote. It also “did not ensure all necessary departments and committees were involved to ensure continuity of care for morgue services were provided.”

State public health officials declined to say how common or unusual it is for hospitals to keep bodies in their morgue for days and weeks. The agency said there is no specific rule dictating how long a person’s remains are stored, but it is expected that hospitals will establish and follow policies for the custody and transfer of deceased people, including notifying responsible parties and next of kin.

The San Diego Union-Tribune filed a California Public Records Act request with Palomar Health for a copy of its corrective action plan related to the Anderson complaint — and any others it submitted to the state in the last three-plus years.

Anderson was born in La Grange, Ill., in 1925, the youngest of three children. He enlisted in the Army as a teenager in 1942, just after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The young private was dispatched to the European theater, where he fought in the historic Battle of the Bulge.

He was awarded the Bronze Star and Distinguished Service Cross after circling around a German machine gun nest that had pinned down his unit and engaging the enemy, his family said. When his rifle jammed, he used it as a club and eliminated the threat, they said.

Anderson is scheduled to be interred early next year at Arlington National Cemetery, an honor that has been delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.