Andrzej Stefanski woke up in a hospital bed, disoriented and heavily medicated. Memories flashed through his mind.

He tried to escape, but the hospital staff confined him to his bed, placing mittens on his hands and a guard at the door.

“I don’t know if I will get out of here alive,” he said to his eldest daughter, Susan Stefanski, over the phone that Thursday in August. He was terrified, a feeling all too familiar to a Polish survivor of the Holocaust.

Susan took him home two days later. She calmed him down, patiently listening to help him understand what had happened.

“You’re gonna be OK, Dad,” she said. “You were in the hospital for an infection — you need to rest.”

Andrzej, who is 96, is one of the last Polish Holocaust survivors in Los Angeles.

Most survivors are in their 80s and 90s, and their numbers have dwindled in recent years as age has taken its toll. The COVID-19 pandemic put them at even greater risk, and hospital visits such as Andrzej’s increase the possibility of contracting the virus.

When all the survivors are gone, no living reminders, no witnesses will remain to the worst human beings can do to one another.

“When Holocaust survivors tell us their stories … they give us a part of their lives. We not only discover the unimaginable pain and horror, but also find resilience, resistance and hope,” said Stephen D. Smith, executive director of the USC Shoah Foundation. “It is vitally important we do not write this remarkable generation out of history.”

The incident in the hospital wasn’t Andrzej’s first flashback. When Susan was a child, he would wake up, terrified, yelling, she remembers. He rarely talks about his feelings, Susan said, but gets emotional when he speaks about the war.

“He kept the anger,” Susan said. “He would say that he wanted people to know what happened. And he doesn’t want people to forget.”

::

Andrzej remembers hearing the radio announcement from his home in Warsaw in 1939, when the war in Poland began. He was 13, fatherless and an only child. As the bombs dropped around the city, Andrzej’s middle school class grew smaller each day.

He spent nearly his entire teenage life in the war.

He turned 19 in 1944, during the fifth year of German occupation. That summer, Poles in Warsaw, Poland’s capital, rose up against the Germans. Andrzej participated, guiding soldiers through the trenches. The fight, the largest single resistance action of the war, lasted 63 days.

He vividly remembers Hitler’s command blasting through the radio when the Polish troops were forced to surrender: “Kill them all.”

In January, I found out that many of my Polish relatives were killed during the Holocaust.

After the Warsaw Uprising was crushed, Nazis captured Andrzej and deported him to forced labor in the German city of Magdeburg.

Some 1.5 million Poles were deported to Germany for forced labor during the war, and they form a large part of the estimated 1.8 million Polish civilians killed during the Holocaust.

The deaths of Poles come in addition to the Jews murdered in Poland under the Nazis. At least 3 million Jews in the country were killed — roughly half the total number of Jews killed during the genocide. The Nazis also sought to suppress the Polish population and repopulate the country with their own. Poland lost as much as 17% of its people during the war, and Warsaw was reduced to ruins.

Andrzej’s ordeal began during the early winter journey to central Germany.

The Nazis left him and his comrades in a frigid train with a group of Russian soldiers. Andrzej’s hands began to turn purple as he sat in the cold; the train was covered with ice.

“I was completely frozen,” he said. But “somehow I survived … my hands survived.”

Andrzej recalls 26 Russian soldiers being thrown off the train by the Nazis.

They had frozen to death.

Andrzej was forced to work more than 10 to 12 hours a day at the camp, digging and doing other manual labor, he said.

After six grueling months, in April 1945, American troops liberated Magdeburg.

Fifteen years would pass before Andrzej could return home and see his mother, because Poland was under Soviet occupation.

He went to Italy and then England before moving to Los Angeles in 1958. Friends had made the journey first, and, unlike Germany, “there is no frost in Los Angeles,” he said.

::

Andrzej speaks five languages: Polish, German, Italian, Spanish and English. It was important to him to learn the languages everywhere he lived, Susan said. He made sure his daughters were multilingual too. Susan and Dorothy both learned Polish, Spanish and English. Dorothy also learned French.

In Europe after World War II, Andrzej worked as an engineer. When he arrived in the U.S., he eventually became a real estate agent. This also is where he began answering to the anglicized version of his name: Andrew. Now that he’s retired, he spends most of his days with Susan at their Westchester home.

Stooped over with age, he uses his walker to stay mobile. Daily exercises and home-cooked meals ensure his good health. He rides his stationary bike about 20 minutes a day and soaks in the afternoon sun in the backyard, taking intermittent naps.

When he talks about the war, he does not use the word “Nazi.” He says “Germans.” He will not use the term “labor camp”; he instead identifies the place he suffered by name: Magdeburg.

When asked how many friends died during the war, he wavers.

“It is impossible to know,” he said.

He must be prompted to describe his experiences as a slave laborer, and even then, he is most comfortable with the shortest of answers:

Susan: “Did [the Nazis] hit you?”

Andrew: “Yes.”

Susan: “Did they hit you all over?”

Andrew: “Yes.”

::

When he was able to return to Poland in 1961, Andrew, as he was known by then, could barely recognize his hometown.

“The whole city was ruined,” he said. “It took years and years before [it] was rebuilt.” The letters he and his mother wrote to each other after the war were censored by the Soviets.

During Andrew’s visit, he met a woman named Wanda Korzeniowska through a newspaper ad. They wrote to each other on his return to Los Angeles, and in 1963, she moved to the U.S. to marry him. Susan, their first daughter, was born later that year.

Marion Lewin and her twin brother, Steven Hess, were sent to the Nazi camps as young children and knew little of their previous life in Amsterdam — until now.

Four years later, Dorotka (Dorothy) Stefanski came along. Wanda died in 2006, and now Susan lives with her father in the home where she and Dorothy were raised.

Despite their father’s role as the president of a local Polish veterans’ group, Susan and Dorothy didn’t know Andrew was in a labor camp until about 15 years ago.

“We knew he lived through the war,” Susan said, “but we just knew very little about it.”

That’s a common experience for the children of survivors, many of whom tried to build lives outside their memories of that terrible time, researchers say. Often, survivors chose not to tell their families about their experiences until they were elderly, if ever.

“In the immediate years following the Holocaust, the public by and large did not create spaces where survivors were invited to share their traumatic experiences,” said Michael Morgenstern, survivor outreach coordinator at the Holocaust Museum LA.

Perhaps at an older age, “they also felt that this was the stage in their lives when they had the adequate time and energy to cope with their painful past.”

::

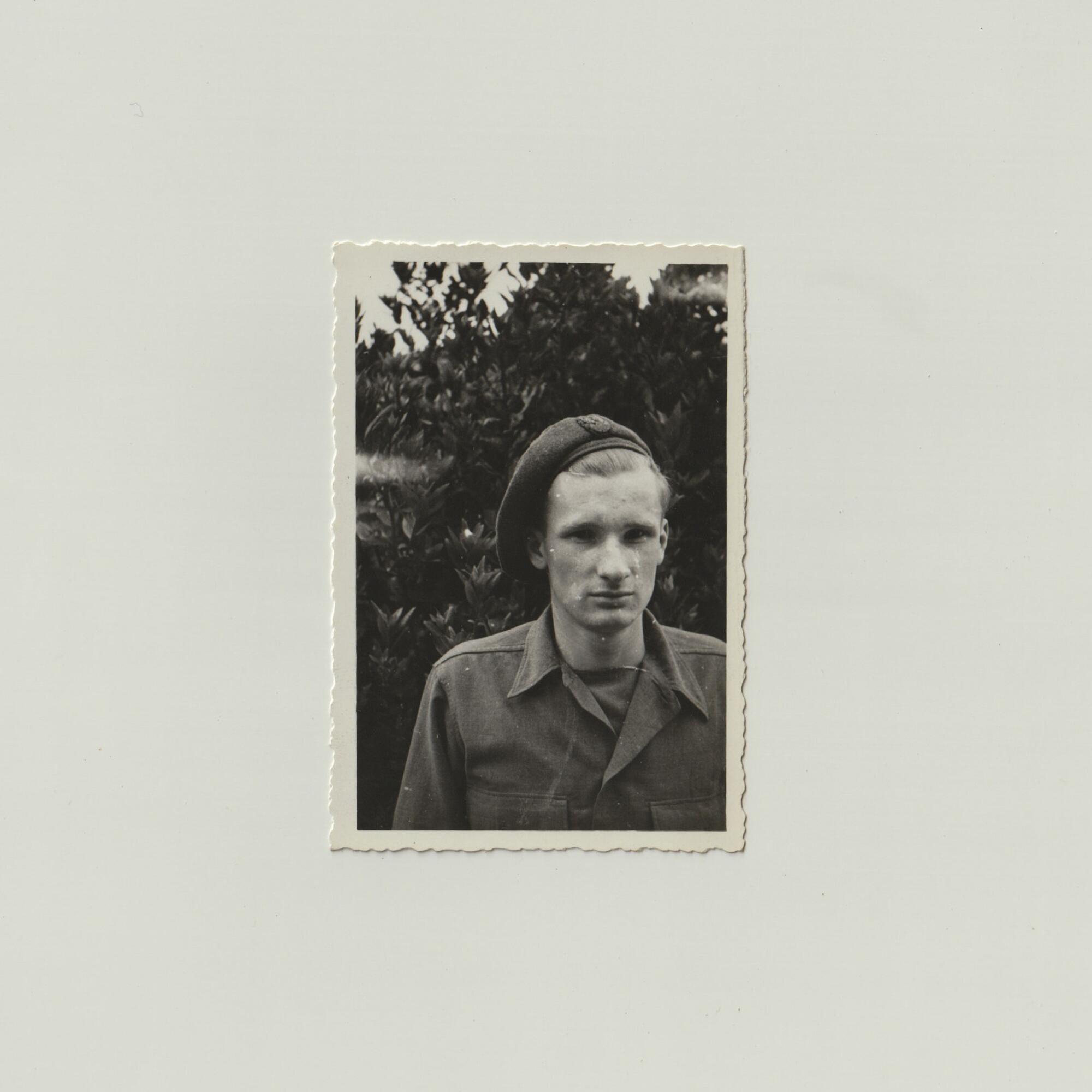

A box of photos in Andrew’s closet remained unexplored until September. He has kept the box, inscribed, “American Red Cross Prisoner of War Food Package,” for more than 75 years.

The box contained photos taken of him in uniform in 1946 — right after the war. His memory has begun to fade, and he cannot recall the occasion or what the uniform signified.

“I didn’t know you had all these photos,” Dorothy, 54, said to her dad when she visited one day. “That box could go into a museum.”

Dorothy said hearing about her dad’s experience is still difficult.

“I think he didn’t want to relive it,” Dorothy said, reflecting on his decision to keep his experience secret. She adds, “I knew he had had a lot of hardship, but I almost don’t want to know. … I still am not comfortable asking him about it because it makes me so sad.”

Learning about her father’s experience in the war has helped Susan understand him more, she said.

“He’s always been a workaholic,” she said.

If he wasn’t working, he was volunteering, taking classes or improving his house or his properties, Susan said. “I don’t think he ever knew how to work the remote control on the television set.”

Being in the camp gave him a particular philosophy: “He did say to me once, ‘If you don’t work, you die,’” she said.

Justin Keeling, Susan’s son, said he’s tried to ask his grandfather about the past. All he’s gotten is “silence in return.”

“Sometimes there are no words to express grief,” Justin said. “It just sits in you.”

::

Susan tends to her father with the help of a caretaker. Now that Andrew is back home from the hospital, they accompany him to his doctor’s appointments, make him home-cooked meals and hang out with him in the backyard on sunny days.

Because of her father’s frailty, Susan said, going out with him during the worst of the pandemic in Los Angeles “was frightening” before vaccines became available and the family was inoculated. Thousands of Holocaust survivors were infected with COVID-19 last year. In Israel alone, 900 survivors died of the virus.

Andrew and his girlfriend, Gwen Van Dam, have been together for over 14 years. But during the pandemic, they chose not to visit indoors for safety. “It was hard for him,” Susan said, “but they still called each other every day.”

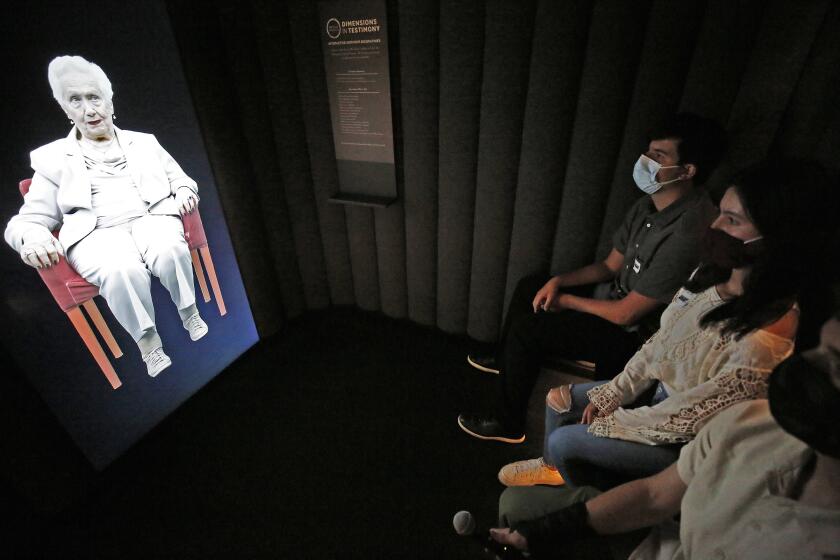

Visitors can have a lifelike conversation with a holographic image of Holocaust survivor Renee Firestone, 97.

Now, when Andrew is feeling well, Susan will take him to their favorite neighborhood restaurants or their church down the street. Occasionally, he and Gwen visit outside.

On Oct. 10, he celebrated his 96th birthday with Gwen, his daughters and other loved ones.

“I think he can go to at least 102,” Susan said.

Some days, though, such hope is harder to hold onto. One summer Saturday when Susan and her father attended Mass together, Andrew slumped over mid-sermon.

Susan caught him before his head hit the wooden pew. She squeezed his hand and asked if he wanted some water. Andrew fell again a moment later.

When the priest greeted Andrew at the end of the service, Andrew told him, “I am dying.” Later that day, Andrew went back to the hospital yet again. His infection was still there.

In September, Justin came home to stay with his mom and grandfather in Westchester after graduating from college in San Francisco.

One evening, when Andrew was headed to bed, he walked past Justin on the couch in the living room. Justin looked up.

“How are you doing, Grandpa?” he asked.

Andrew turned and stopped ever so briefly before walking away.

“I am surviving.”

Photo editing by Jacob Moscovitch. Additional editing by Maria La Ganga, Keith Bedford, Hector Becerra and David Lauter.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.