YERMO, Calif. — A certified letter arrived April 8 for Fred E. Budinger Jr., from the federal Bureau of Land Management. It read like an eviction notice and came across like a punch.

Dear Mr. Budinger:

The Bureau of Land Management proposes to remediate the remnant archaeological excavation and study features of the Calico Mountains Archaeology District because they pose a significant threat to public safety.

Budinger stopped. Remediate, he thought: Orwell would spit at a word like that. Officials at the federal agency, in his opinion, had treated the Calico Early Man Site as nothing less than a nuisance. Now they were getting rid of it.

“This is a destruction project,” he told his wife, Pam.

Pending permits and approvals, the Bureau of Land Management next year will remove vandalized buildings from the site in the central Mojave Desert and fill all but five of the primary excavation pits with dirt and polyurethane foam. Visitors may still tour the site, but for Budinger, the bureau’s decision signaled the end of the most promising chapter in North American archaeology.

A dissertation shy of a doctorate, he is an archaeologist whose objectivity drops when he thinks of such an unheralded conclusion. At 75, he has committed his life to these 100 acres in the Mojave and isn’t about to let them go.

This is it, he thought: the last stand.

::

Travelers on Interstate 15 east of Barstow might have a hard time imagining this region of California thousands of years ago, when bands of hunters roamed the edges of lakes and prowled grasslands in pursuit of bison, mammoth, horse and camel.

That world is a mirage cast upon today’s desolate vistas and lonely offramps, but for archaeologists, the emptiness has been an invitation for studying the settlement of the New World. Rattling across dusty roads, tracing alluvial fans and exploring mining claims, they have spent lifetimes trying to raise the past.

They first came upon Calico, a sun-blasted bentonite claim, in the 1940s and were intrigued by chunky stones that littered the ground and looked like hand axes and scrapers. Years later, they came to believe that this was the site of an ancient workshop for manufacturing tools for digging, scraping and butchering.

But not everyone agreed, and the site became the subject of fierce debate, kindled by those who believed that some artifacts were more than 200,000 years old and those who dismissed that belief as nonsense.

Budinger has long championed the site’s antiquity. Bolstered by the opinion of the most esteemed archaeologist of the age, Louis S.B. Leakey, and his colleague on-site, Ruth DeEtte Simpson, he enlisted other experts along the way. Most are dead, and he stands almost alone.

Sitting at his computer with the Bureau of Land Management letter, he collected his thoughts. The federal officials seemed to believe that Calico was important only for its recent history and the personalities it had once attracted. But they were wrong.

Calico was a place for research that had to be protected for a new generation of archaeologists and geologists. He could never think of it as just a tourist destination for travelers on the way to Las Vegas.

::

In 1974, Budinger was working at the front counter of a chemical supply house in San Bernardino when he learned that the county parks department needed someone full time at Calico.

“Patience, patience, patience.”

— Louis S.B. Leakey

He couldn’t believe it. As an undergraduate, he had ditched biology for anthropology, drawn to the promise of working outdoors, and Calico was the most exciting archaeological site on the continent, rivaling that riverbed in Folsom, N.M., where a cowboy found a projectile point among bison bones in 1908.

Budinger applied for the job, and in less than two weeks, he was driving his ’59 Ford over the Cajon Pass. Friends tried to wave him off. With his fate tied to Calico, doors would close in his face, they warned, but he didn’t care.

Simpson, the project director, ran the camp like a drill sergeant: No talking in the pits, no joking, all business. She was in her mid-50s and had walked these hills for almost 30 years, most notably in the company of Leakey himself.

The two had met in London in 1958. Leakey was taking a break from fossil-hunting in Tanzania’s Olduvai Gorge, and Simpson had sailed to Europe weeks earlier to share with European archaeologists Calico’s best surface artifacts.

The two had dinner. He tore apart bread rolls to show her chipping and flaking techniques, and in 1963, he toured the Calico site, the first in a succession of visits that eventually led the National Geographic Society to put up nearly $50,000 for field work.

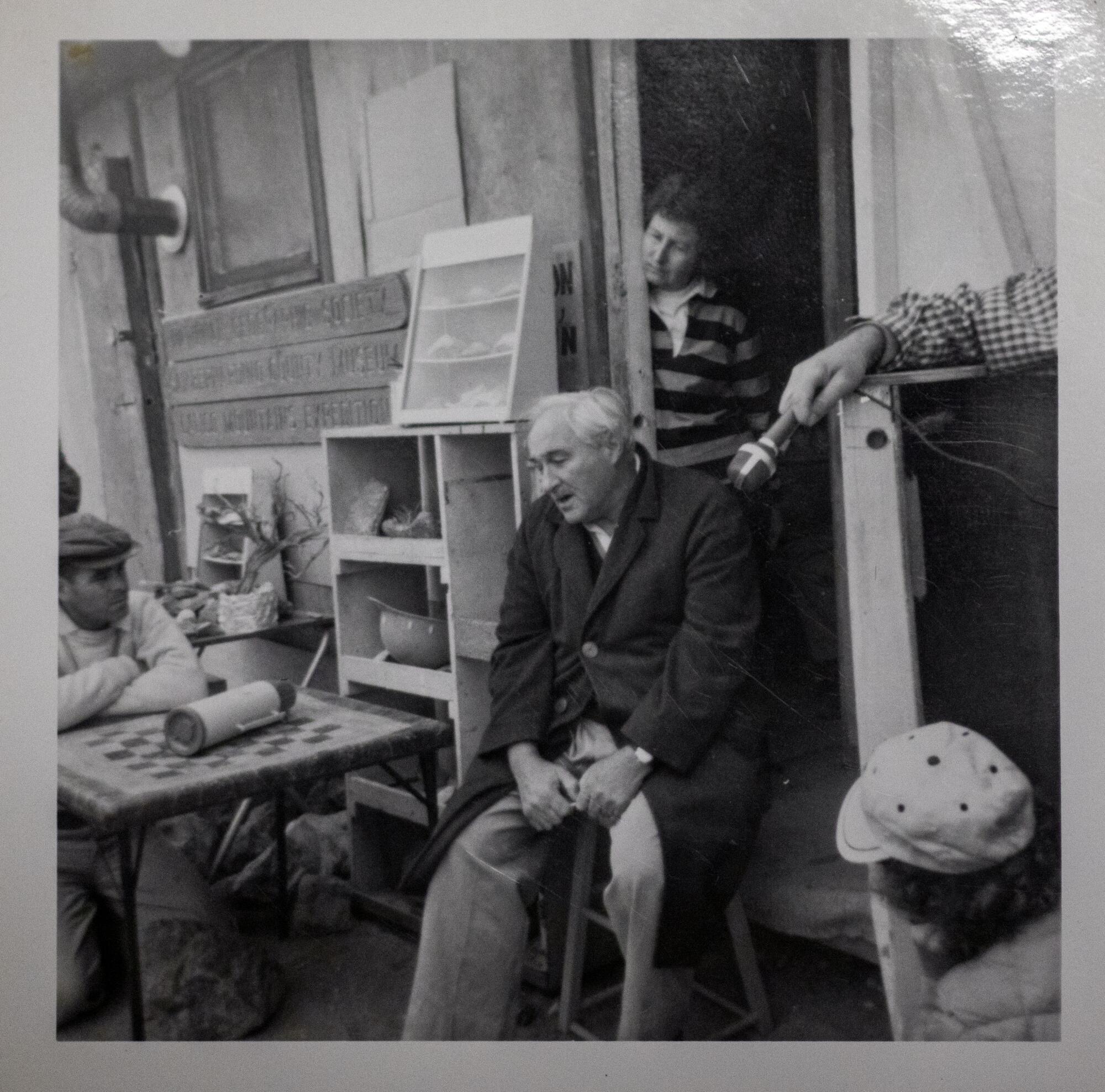

Excavation began Nov. 1, 1964. Through rain and mud, under the light of Coleman lanterns and under the blazing sun, crews chipped away at the rocky surface, three inches at a time, uncovering stones that were believed to have been shaped by hand.

“Patience, patience, patience,” Leakey counseled, as he hobbled — cane in hand — around the site, accompanied by Simpson and a former Army paratrooper hired as bodyguard for protection against legions of fans. Excavated material was recorded, boxed and shipped to the San Bernardino County Museum, where it was stored like the jumbled pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

Some pieces, which reminded Leakey of hand axes and chopping tools shaped by Homo erectus more than 100,000 years ago in east Asia, led him to believe that Pleistocene man had stood here, on the eastern side of the Pacific.

In 1970, the Leakey Foundation organized a conference in San Bernardino that drew archaeologists from around the world. “From this weekend on, a new chapter will be written in the prehistory of America,” the silver-haired sage told the assembly.

But the conference only sharpened debate. In 1973 — one year after Leakey’s death — the journal Science published a paper arguing that the artifacts might be stones chipped and flaked through natural collisions caused by flash floods over millennia.

For years, naysayers had been floating that theory, and Leakey and Simpson had tried to brush it away. After the Science article, there was no avoiding it.

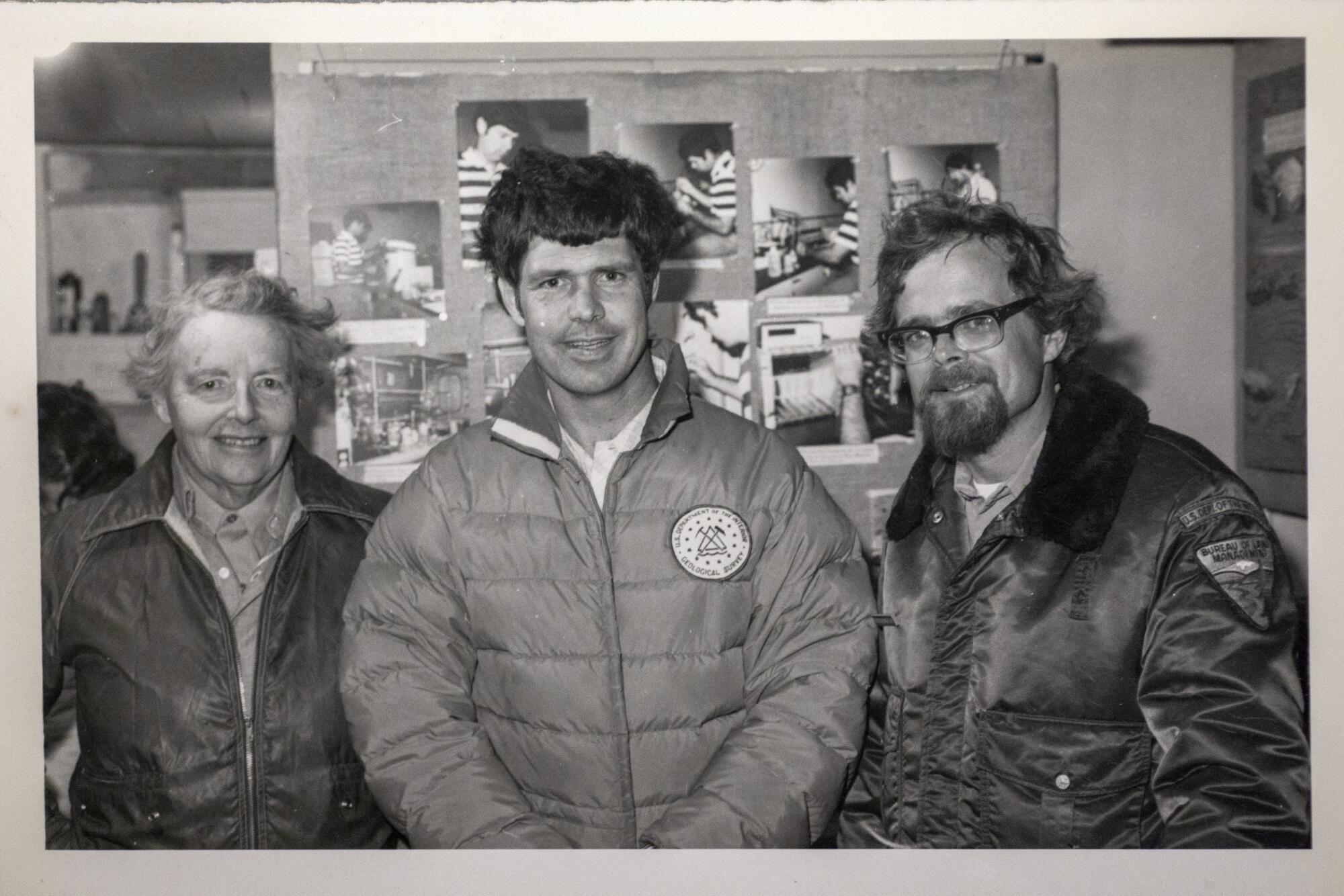

Simpson, grieving the loss of her mentor, needed allies, and Budinger, with horn-rimmed glasses and, eventually, a county park ranger uniform, had arrived: an underdog championing an underdog.

::

Settling in, Budinger got to work, coating roofs with asphalt paste, building steps and raising guard rails. He bunked in a prospector’s shack and provided around-the-clock security.

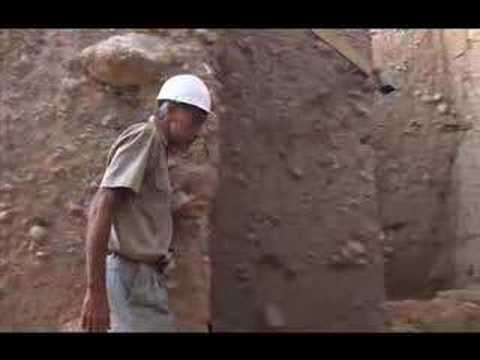

A quarter-mile uphill were the excavation pits and trenches, scattered over the creosote-studded hillside. Soon numbering nearly two dozen, most were the size of single- or double-wide trailers and as deep as 25 feet. One would soon plummet 77 feet.

Lying in the dirt, Budinger took out his hammer and chisel and began picking and scraping at the calcium-hardened soil, listening to each tap, its pitch dropping in the proximity of a stone.

One day he unearthed two small blades of stone, triangular with sharpened, serrated edges. He called them “steak knives” and felt a surge of adrenaline. He imagined the moment of their creation: suppertime in the Pleistocene.

After a day in the pit, he might hike to the top of the hill and gaze out over the broad expanse of desert, cast in the light of a setting sun. From that perspective, his life made sense. He was at home.

He had been on-site almost five years when two experts — from USC and the U.S. Geological Survey — agreed to date the mineral coating that had formed on six artifacts singled out by Simpson.

Budinger was thrilled, because Calico was ignored. Even the parks department questioned its value and had asked him to move off-site.

With the passage of Proposition 13 and a loss of tax revenue for San Bernardino County, the Bureau of Land Management took over, and a leaner federal budget gave Budinger the idea of starting a nonprofit for fundraising. It would be called Friends of Calico Early Man Site Inc.

Little did he know that Friends would create so many enemies.

::

In 1981, the journal Geology published a paper that summarized the dating. The mineral coating had accumulated about 200,000 years ago. The news was a stunning rebuke to those who believed that humans arrived in the New World no more than 13,500 years ago.

But the findings inflamed critics who argued that their extreme age proved only that the rocks were chipped by natural forces.

Budinger persevered. He invited more experts to the site, and he took it upon himself to test Calico’s most extravagant claim. In the early years of the excavation, archaeologists uncovered a semicircle of stones that Leakey and Simpson interpreted as a hearth where humans had huddled, the earliest evidence of domestic fire in the New World.

Analysis confirmed that one of the stones had been heated by flames, but Budinger felt that if Calico were to gain professional respect, more testing was necessary. Simpson agreed, so in 1985 he asked Caltech to analyze another stone. The results came back negative.

Simpson was crushed, and Budinger — according to his account — paid the price for challenging her most prized find. Her allies mounted a campaign against him.

Liability on the property had always been an issue. A rusty nail or a loose rock posed a danger that could lead to a lawsuit, and Friends of Calico would be liable.

The board asked Budinger to buy insurance for himself and for the site. It was an impossible request. His salary could not cover the costs, and the board members knew it.

They had fired him.

::

Angry and disappointed, Budinger had to find a job. He taught high school in Barstow. He started working for an engineering firm. He got married and divorced and married again. He earned a master’s degree and began thinking of getting a doctorate.

He retained his membership with Friends of Calico, however, and continued to visit the site on weekends, but the mood had changed.

‘I will always take care of Calico.’

— Anthropologist Fred Budinger

Calico had always welcomed volunteers, and Friends of Calico catered to these dedicated amateurs. Many were retirees who had always wanted to be archaeologists. Some said they were inspired by “Raiders of the Lost Ark.”

Their work, Budinger said, became more social than scientific. Meanwhile, the professional community continued to disparage the site.

When Jim Shearer, the Bureau of Land Management’s archaeologist for the Barstow field office, was a student in Utah in 1999, he asked about Calico, and his professor shot him down. “If you ever have any thought about being an archaeologist, you’ll never ask such a stupid question.” [Expletives deleted.]

In declining health, Simpson grew discouraged. She tried to write a paper about Calico, but a stroke made that impossible. Budinger visited her with chocolate ice cream and a promise.

“I will always take care of Calico,” he said.

“I know you will,” she said.

Simpson died in 2000. A small memorial service was held at Calico, where Budinger unveiled a brass plaque with an epitaph that acknowledged her work:

A singular voice in North American archaeology.

::

After years of struggling over finances, the Calico Early Man Site was suddenly rich. Simpson left close to $600,000 to Friends of Calico, money to be used for research and long-delayed maintenance projects. The board, which had invited Budinger back during Simpson’s illness, named him project director.

But in 2006, the Bureau of Land Management abruptly changed course. The agency declared the pits unsafe. Their depth, the steepness of the walls and the lack of shoring put them out of compliance with Occupational Safety and Health Administration regulations.

Budinger was shocked. The walls were like concrete. He asked if he could collect his tools.

“No,” the bureau’s field manager said.

“What if I go in?” he asked.

“You’ll be arrested,” he recalled being told.

He tried to fight the decision. Halfway through a doctoral program at the University of Cincinnati, he needed access to the pits to complete his research so he could start writing his dissertation.

But once again, the Friends of Calico turned on him. At a spring membership meeting, its board surprised him with a memo listing 42 complaints, ranging from “fostering hostility and mistrust” toward co-workers to “insubordination” for defying the Bureau of Land Management’s order not to enter the pits.

Most hurtful was the claim that his research was “shoddy” and had damaged Calico’s reputation. “It was like a cold knife cutting me down the middle,” he said.

The board gave him five months to conform, but according to Budinger, members stopped answering his emails and phone calls.

Then, one day, he got the message: “Fred, you’re gone.”

::

Adella Schroth, curator of anthropology at the San Bernardino County Museum, became Calico’s new project director and champion.

“It’s the oldest active dig in the U.S.,” she told a local newspaper, “the only archaeological site in California where the public is allowed to participate. We welcome everyone.”

Friends of Calico still met on-site the first weekend of each month from October through May. They avoided the deep pits, scraped at shallow soils and laid out potluck suppers that included Leakey Limey-ade (cherries, lemons and gin) and Leakey’s dessert (brandy and milk).

Behind the scenes, the spirit of discovery that had inspired archaeology’s elder statesman and Simpson was quickly slipping away. By 2014, Simpson’s bequest was worth a little more than $100,000, and Friends of Calico opened a GoFundMe page.

“Unfortunately, due to the downturn in the economy/lack of donations, and cost increases across the board, we find ourselves in jeopardy,” the organizers wrote. With the goal of raising $1 million, the campaign stopped at $4,200.

At the museum, Schroth combed through the Calico collection and discarded more than half of the nearly 70,000 pieces. She said they either lacked data or were just rocks. She and a colleague sent 15 artifacts to an expert at the University of Washington, who determined that the oldest was a little more than 11,000 years old.

Would a remote spot in the California desert upend our understanding of when humans arrived in North America? I had to dig in.

They wrote up the findings. Schroth hoped their paper would settle the dating controversy “once and for all.” Peer-reviewed, it was never published. Schroth died in 2018.

“After her death,” her coauthor wrote in an email, “we couldn’t get into her computer to recover either the comments or the parts of the papers we had rewritten.”

::

The vandalism started when thieves cut the lock to a gate across the road and, once on-site, broke doors off hinges and stole a generator, propane tanks, two refrigerators, tools, kitchen equipment, artifacts and books.

The county sheriff responded, and the Bureau of Land Management tried to secure the site. The break-ins continued, with intruders tearing at standing walls for electrical wire.

With Calico in ruins, the Bureau of Land Management had to decide the site’s future. Lacking funds for on-site management, the agency had no choice but to implement a plan that would ensure the safety of unsupervised visitors.

On a recent visit, Katrina Symons, field manager for the bureau’s Barstow field office, surveyed the damage. The largest building lay twisted on the ground, its corrugated steel roofing partially torn off, one wall splayed into the desert. Torn sheetrock littered the floor of another building, its walls shredded. Fencing to the excavations had been peeled back.

“How do we make this site safe from a management perspective?” Symons asked. “It is like threading a needle: finding the best balance between protecting features and protecting the public.”

Budinger says he will never return, but he doesn’t need to.

Each morning he fills a Thermos with decaf and settles into his office in his home in San Bernardino. The small room is organized around two desks, four filing cabinets and shelves loaded with books and three-ring binders, all devoted to Calico.

He recently signed a confidentiality agreement with the Bureau of Land Management and has a copy of the report that the agency commissioned before coming up with its remediation plan. Costing $61,675, the report is 438 pages long, and after a few weeks of digging through the document, he is encouraged.

“The thing is so full of holes I could drive a Mack truck through it,” he said, “and I will.”

As he sits at his desk, memories come back of old friends — scientists and snowbirds, the dedicated and the infuriating — and of the walk he once took to the top of the hill at sunset to survey the ancient land, when so much seemed within his grasp.

“Consider yourself blessed,” he said, “if you have a passion for anything. Passion is a way of organizing your life; otherwise you go off in 20 different directions, and in the end, you wonder what you have.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.