Before he was a janitor, he was a legend. At Park La Brea, he met a tragic end

José Tomás Mejía was a legend to his brothers and sisters in the Salvadoran town of Moncagua.

They heard how he fled to San Salvador when he was 14 to avoid being forced into the military during the civil war. How he left the country when he was 17 and ended up being assaulted, robbed and left in Mexico with nothing. How he slept on empty cement bags every night at the construction site he worked at until he saved enough to journey to the U.S.

He was the only one of seven siblings his mother did not call by name. “Mi niño,” she called him. The letters Mejía sent from America became the textbook their mother used to teach the younger ones how to read.

When Fermín Pineda arrived in the U.S. five years ago and finally met his big brother, he was not disappointed.

Mejía was a janitor, known and trusted by tenants and admired by co-workers, at an apartment complex where he made $17 an hour. He spent lunch breaks helping negotiate a new contract for himself and fellow workers. When a car drove into a crowd of people during an immigrant rights rally in Orange County, Mejía jumped on the hood in an attempt to stop it.

Last year, the 50-year-old accomplished his dream of buying a home in L.A.

No one expected Mejía’s story to end on the fifth floor of a tower at Park La Brea, where he had worked for more than three years. Or that his life would be cut short by an assailant no older than he was when he fled his homeland.

“His dream was snatched away in a cowardly way. We can’t understand it,” Pineda said. “For me, José Tomás Mejía is not just a name. It’s the title of a story. The title of a book. Because there’s so much to tell about him.”

Mejía’s family lived in a rural part of Moncagua where carts pulled by oxen got stuck in mud.

The boy shared a bed with his mother and four siblings in a 13-by-20-foot home. Before he had reached his teens, Mejía promised he would one day move his family to a place where there was room for them all.

But first, he needed to survive the country’s civil war, which pitted rebels against a right-wing government backed by the U.S. More than 75,000 Salvadorans died; millions more fled.

After a friend was shot in the leg by a civil defense group that mistook him for a guerrilla fighter, Mejía decided it was time to leave. He moved to Soyapango in San Salvador, 75 miles away, and lived with an uncle, Raúl Mejía. There, Raúl supported him, bought him school uniforms and had his older daughter help him study.

“I supported him in the worst times,” Raúl said. “Whatever he needed.”

When the conflict reached Soyapango, the family took apart their beds and put the mattresses up against the walls to try to protect themselves from bullets. Eventually, they fled to Nueva Granada.

They spun around the dance floor, as lighthearted and energetic as teenagers.

Mejía, now 17, decided that it was time to leave once more. Because he was a minor, he had to travel back to Moncagua to get his mother to sign documents allowing him to leave the country.

But when he arrived in Mexico, Mejía was assaulted and robbed. Left with nothing, he slept on park benches until a man offered him a job at a construction site. He spent the nights where he worked, using empty cement bags as cushions.

“Even then, he didn’t give up on his dream of reaching the United States,” Pineda said.

Mejía’s mom didn’t hear from him during that turbulent time. She thought her son was dead. It wasn’t until he reached Los Angeles in 1991 that he could write to tell her that he was OK. Soon after, he secured a job as a janitor at Toyota offices in Torrance.

Within a few years, he’d sent enough money home to El Salvador for his family to move into a new home.

By the time Mejía started working at Park La Brea, he had more than two decades of janitorial experience under his belt. And he was a married man, having met Dora Molina, also Salvadoran, on a dance floor in 1994. He helped bring her three children from El Salvador to the U.S.

His arrival in 2018 ushered in a marked improvement for the residents living in Towers 33 and 34. Chan Rudrapatna would see him every morning around 8 a.m., changing trash bags outside. Mejía cleaned every inch of the building, she said, including doorknobs, mirrors and the walls and buttons in the elevator.

“He was not someone who took his job casually,” Rudrapatna said.

Mejía was also there for Rudrapatna in tough times. Last year, when she told him her mother had died, Mejía came to offer his condolences. After he finished work, he knocked on her door and spent 20 minutes trying to comfort her.

“I just don’t want you to feel that sad,” he told her, “because you have your family and they need you.”

Tenants came to expect him greeting them each day with a beatific smile. They learned his name from the patch that read “Jose” in red lettering on his work shirt. In the mornings, Igor Chase’s 4-year-old daughter went looking for Mejía so she could say hello. When she heard him vacuuming in the hallway, she’d open the door to give him fruit or a snack.

He put in decades with the Service Employees International Union-United Service Workers West. And he rose up the ranks. He was elected by his peers to serve on the local chapter’s executive board.

“He was walking the walk on the change he wanted to see in the world and put a lot of his life into helping others,” said Alejandra Valles, secretary treasurer and chief of staff of the SEIU-USWW.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

On June 16, Mejía headed to Tower 33 to work. Around 1:15 p.m., he spoke with his wife and told her to take a bus to get groceries and that he’d pick her up at the supermarket after his shift.

That afternoon, around 2:30 p.m., a 17-year-old came to Tower 33. He’d had a dispute with a building resident and was aiming to “harm” that tenant, said L.A. Police Det. Sean Kinchla.

But the suspect encountered the janitor, and there was “a confrontation,” police said. Mejía was found — stabbed to death — in the fifth-floor stairwell of the Park La Brea tower.

Mejía’s keys had been taken, likely because the suspect was trying to get into the tenant’s apartment, said Lt. John Radtke. The keys were later recovered at the scene.

The teenager fled on foot and was later arrested. He is facing a murder charge; his defense team has raised doubts about whether he is competent to stand trial. Police are not releasing his name because he is a minor.

At 4 p.m., as Molina headed to the market, she called Mejía. He didn’t answer the phone. An hour later, she stood next to a full cart waiting for her husband to arrive and pay for their groceries.

“Where are you?” she texted him. “Why aren’t you answering?”

When Mejía’s cousin called and told her he would pick her up, she left the market sobbing. She thought Mejía had been in an accident.

“I never thought it’d be something like this,” Molina said. “He didn’t deserve this.”

The day after Mejía’s death, residents stopped to pay their respects at a small memorial erected by union members outside Tower 33.

People, some making the sign of the cross, stopped to look at photos of the smiling custodian.

Word among the workers and tenants was that the suspect wanted to get into his girlfriend’s apartment and believed the janitor’s keys would open the door. According to Valles, Mejía’s keys didn’t open apartment units.

Still, “Tomás wasn’t giving up the keys,” Valles said. “It’s the building that he’s in charge of cleaning and keeping safe. Knowing Tomás, he fought.”

“In loving memory of José Tomás Mejía,” read one poster, which included a link to a GoFundMe to help Mejía’s family. On another board, residents had written messages — “thanks for your positive energy every morning we met at the lobby of Tower 33”; “Jose you were an angel for us on earth.”

Among those stopping by was Rafael Acevedo, whose boots were caked in mud from spending the morning fixing an irrigation pipe at Park La Brea. He’s worked at the complex for more than 20 years.

When he learned the news the day before, he wept. He’d known Mejía since 1994; Acevedo’s wife is Mejía’s wife’s niece. Acevedo is familiar with loss; in 2016, his brother was shot to death in Guatemala.

“But here?” he said. “You’d never think something like that would happen in a country like this.”

The women planted their bodies and kicked one foot forward, imitating the self-defense move displayed on a projector screen: La patada hacia los testiculos.

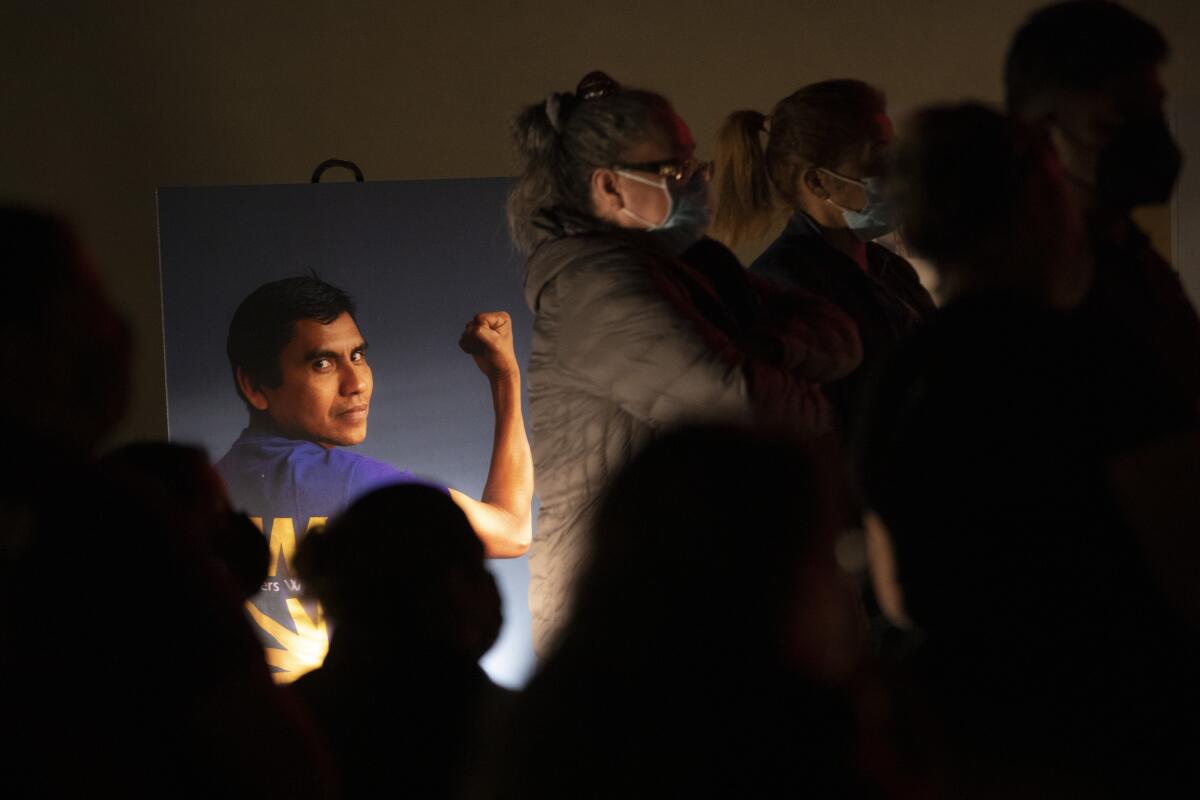

That evening, more than 50 people gathered for a vigil in the darkened parking lot of the union’s Southern California headquarters on West Washington Boulevard, the few lights coming from a path of candles. Mejía often told his wife that this building was his second home; the union, his second family.

When he finally purchased an actual home, receiving the keys on his birthday last September, the house was less than four miles from the union building. He planned to use one of the rooms as his office for union organizing.

“I don’t know where he got so much strength, so much energy,” said Molina, who described her husband as having a childlike happiness.

Against a backdrop of enlarged photos of Mejía, who smiled in nearly every one, dozens of his fellow union members shared memories. Among the attendees was L.A. City Councilman Kevin de León, who fought and marched alongside Mejía.

They talked about the workers who admired Mejía and supervisors who feared him. The time someone pulled a gun on him when he was knocking on doors in Las Vegas to try to turn the state blue. The way he fought for his people, like a true “luchador.”

“Tomás never asked for anything for himself,” Marisol Rivera, a janitor and vice president with SEIU-USWW, told the crowd. “He was for his co-workers. For other people.”

On Saturday, Mejía will be buried at Inglewood Park Cemetery.

He had always planned to return to his homeland one day. But his family agreed that he would be buried in the country where he spent the majority of his life fighting for others.

His mother, now 74, doesn’t want to think of her son dead after so many years apart.

She wants to remember him as he was.

Her niño.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.