Column: A racist mob burned Santa Ana’s Chinatown to the ground. It still serves as a lesson

Behind a row of hipster lofts in downtown Santa Ana is a parking lot where there once stood a Chinatown.

It was a vibrant community that reached about 200 residents at its peak in the 1890s. They were an island in the middle of a city that didn’t want them. In a country that denied them citizenship. During a time when the United States blocked immigration from China altogether. Tenants and business owners withstood racist taunts and physical attacks and repeated attempts by city officials to drive them out of town, even as they washed the laundry of white people and sold them fresh vegetables.

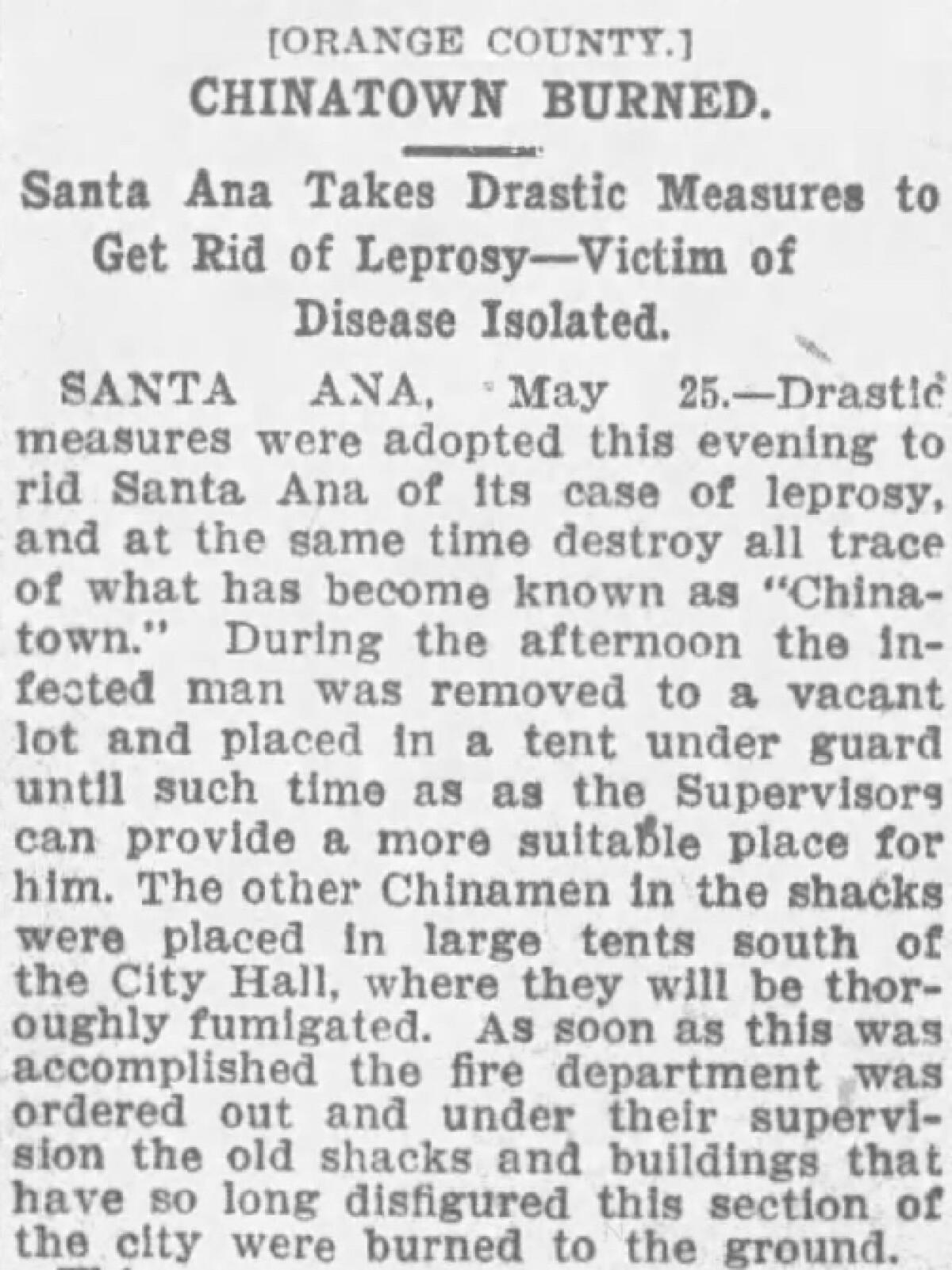

But the hate whittled away at this small Chinatown until just a few houses and other structures remained. Everything disappeared by May 1906, when health officials declared the neighborhood a public hazard after a man named Wong Woh Ye allegedly contracted leprosy. Over 1,000 people showed up on a drizzly night to cheer as firefighters doused buildings with coal oil and set them ablaze.

An eyewitness gushed that it felt like “a big picnic, or a Fourth of July”; this paper said it “was as picturesque an event as could be imagined.” From a quarantine pen surrounded by barbed wire where a Rite Aid now stands, former residents looked on as flames engulfed their businesses, living quarters and a vegetable garden. They received no restitution for lost belongings and were ordered to leave. Ye, meanwhile, was denied treatment by his guards and left to die.

I pass by the parking lot every day as I drop off my wife at her store nearby. I’ve thought about what was once there frequently during this past coronavirus year, as anti-Asian attacks rose exponentially in Orange County and nationwide.

The destruction of Santa Ana’s Chinatown was just one of dozens, if not hundreds, of anti-Chinese pogroms that plagued the West during the 19th and early 20th centuries. But the incident is virtually unknown outside the small world of Orange County history nerds. It’s not taught in local schools, never merited an apology from city fathers and isn’t even commemorated with a marker.

It’s sadly par for the proverbial course when it comes to how the American mind considers anti-Asian violence — namely, we don’t much.

The exploitation of Chinese workers during Western expansion, the de facto and de jure bans on Asian immigrants for decades, the forced removal of Japanese Americans from their homes during World War II and placement in concentration camps. They linger on the fringes of our collective mind like faint blips from our long-ago past with little influence on the present. Individual cases — the 1982 beating death of Vincent Chin by workers who blamed him for the declining American auto industry, anti-Filipino riots in Watsonville in 1930 that spread across California, laws against Chinese- and Vietnamese-lettered signs passed in the San Gabriel Valley and Little Saigon during the 1980s — are dismissed as aberrations.

Too many see what’s happening right now — a study by the group Stop AAPI Hate has listed nearly 3,800 attacks against Asians since last March — as triggered by the pandemic and the aftermath of a toxic presidency. Too many already categorize the massacre of eight people at spas in the Atlanta area this week — including six women of Asian descent — as the butchery of a disturbed loser.

For many Asian Americans, the killings further fueled fears about anti-Asian hatred that has mounted over the last year as police and advocacy groups have reported record numbers of hate crimes and harassment.

“Yesterday was a really bad day for him and this is what he did,” the Cherokee County sheriff’s spokesman, Capt. Jay Baker, said about the accused killer.

Too few of us see all this recent madness for what it is: the continuation of a plague that can end only when non-Asian Americans see the blind spot within us.

It’s great that posts across social media urge people to check in on any Asian Americans they may know. It’s nice to see that neighbors of a Chinese family in south Orange County subject to the harassment of idiot teens take turns as watch guards. It’s important that a House Judiciary subcommittee held hearings this week about anti-Asian discrimination and even used the hashtag #StopAsianHate.

Violence and hate incidents directed at Asian Americans have surged across California since the pandemic, with some blaming Asians because of the coronavirus’ origins in Wuhan, China.

But I fear what’s next: nothing.

This country has had a good 163 years — ever since the California Legislature passed a law that banned “Mongolians” from settling in the Golden State and started this nation’s anti-Asian streak in earnest — to rectify the wrongs we rain down on Asian Americans. The ignominies endured by other racial and ethnic groups brought national reckonings, no matter how imperfect or incomplete. But it seems any time we say we’ll do the same for Asian Americans, historical amnesia pulls us back to where we started.

It’s unfair to lay individual blame on people who were just never taught this past, of course — but it’s incumbent upon the ignorant to learn. I include myself in this group. For instance, I never saw any tinge of anti-Asian bias during the 1992 Los Angeles riots until Korean friends of mine years later told me their families commemorated the anniversary as Saigu (Korean for “4/29”) in honor of what their community endured.

Beth Lew-Williams, a Princeton history professor who studies the history of anti-Chinese hate in the United States, told me in a phone interview that she starts her classes each semester by asking students what they know about Asian American history. “I get them from across the country,” she said. “They struggle to come up with even a single topic.”

She feels that “it’s good that everyone is stopping and reflecting” in the wake of the Atlanta-area tragedy. “But a lot of that stop-and-reflect is that people are shocked and surprised. That just exposes our lack of memory of these earlier incidents.”

Asian Americans can and should organize and rally and proclaim “Never again.” Politicians can and should pass new legislation. Educators can and should teach students about all of this. But until non-Asian Americans collectively force ourselves to treat anti-Asian violence in this country as a continuum, attacks will keep getting diminished. Not doing so is almost as dangerous as the violence itself — because it gives perpetual life to the violence.

“We can’t reason through how to address the larger question of discrimination and feelings of nonbelonging [by Asian Americans] without addressing the longer history and not just this one moment,” the professor said. “If we treat it as a pandemic-specific phenomenon, we’re going to have a problem.”

We’re going to have another parking lot built over a long-forgotten Chinatown.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.