YREKA, Calif. — Inside Zephyr Books & Coffee, visitors are greeted by a turntable spinning vintage vinyl, cozy leather couches, and the smell of java roasted right here in Siskiyou County.

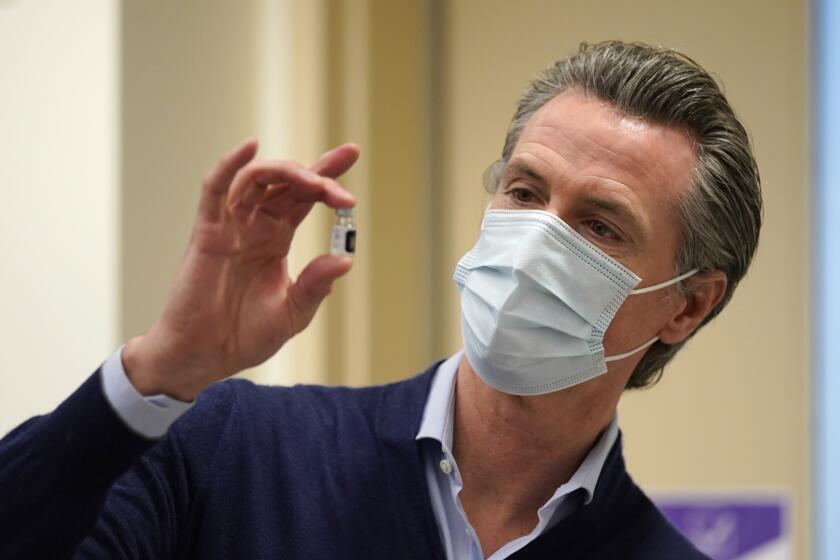

And by the picture window looking out on Miner Street — a stack of petitions to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Owners Debbie and Guy Scott started collecting signatures after Newsom’s pandemic restrictions hit their bookstore in Historic Downtown Yreka hard, even as the virus’ toll felt far removed from this vast rural county that did not report its first COVID-19 death until November.

The husband and wife lost a few customers. But by and large, they said, the effort to oust the Democratic governor is resonating in conservative Northern California.

“Our lifeblood is not corporate money. It’s not government funding,” Debbie said. “We’re family-oriented. We’re ranch-oriented. We’re ag-oriented. We’re small- business-oriented. And Sacramento has a different priority. They’re politically oriented.”

The Scotts are a reminder that, even when it comes to statewide issues, all politics are local.

California’s northern counties have always felt overlooked in the famously liberal Golden State. People here chafe at government regulations that they say have hobbled industries such as timber, fishing and mining. Many believe the state’s high taxes and cost of living have quickened the decline of small towns. They say their voices are drowned out in Sacramento by urban Democrats.

But amid a pandemic that has been so tightly intertwined with politics, they have found in the recall movement a response to their broader frustrations. As the effort gains steam, it feels like a win for this part of the state.

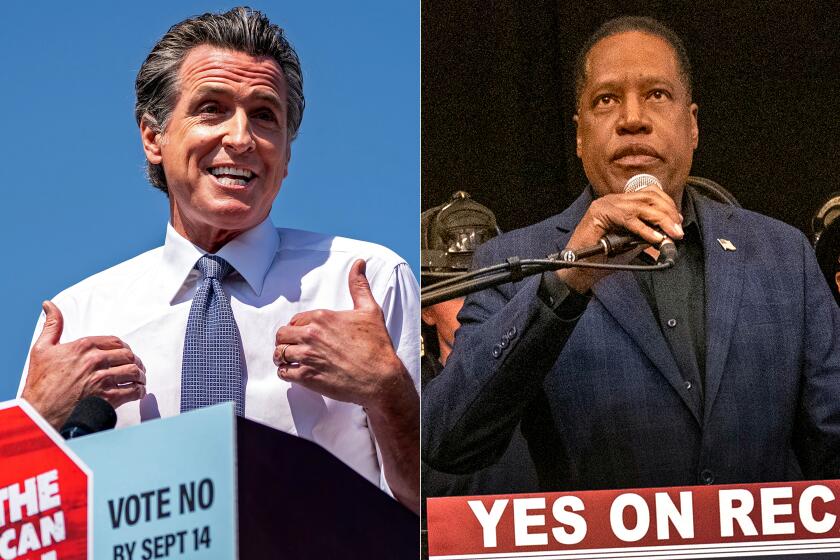

Leaders of the Republican-backed recall movement must submit 1,495,709 valid signatures by March 17 to trigger a special election later this year. This week, backers said they had collected 1.95 million signatures. While those still must be verified by the secretary of state, they say they are confident they have more than enough to qualify for the ballot.

The attempted recall of Gov. Gavin Newsom will go before voters on Sept. 14. Here are the details.

“We’re really well received everywhere we go,” said Orrin Heatlie, the official proponent of the recall effort and a retired Yolo County sheriff’s sergeant. “People are coming from across the entire political spectrum to participate.”

Even if the recall makes the ballot, it will be an uphill battle to persuade enough voters to oust Newsom before his term ends in 2023, especially if schools are open and Californians are widely vaccinated against COVID-19. In a poll released last month by the UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies, only 36% of registered voters said they would vote for a recall; 19% were undecided. Support broke down along party lines.

Tensions between rural communities and the Newsom administration over its handling of the pandemic have been building for months. Smaller counties with fewer COVID-19 cases have balked at the governor’s statewide restrictions, arguing that one size does not fit all. Last spring, some Northern California counties reopened businesses in defiance of the governor’s stay-at-home order.

Dan Newman, a campaign spokesman for Newsom, said “the pandemic has been really hard on small businesses across the state” and that the governor “has gone to great lengths to allow localities to react to it based on the situations in their communities.”

Newman said he believed people were most likely supporting the recall because of partisan politics, not the pandemic — especially in Northern California, which voted overwhelmingly for former President Trump.

“After finally starting to tire of chanting ‘stop the steal,’ this has become a new rallying cry for Trump Republicans in California and nationally,” he said. “More than 6 million Californians voted for Trump. Of course, many of them will support any scheme to try and replace a Democrat with a Trump supporter.”

But state Assemblyman Kevin Kiley (R-Rocklin) jokingly called Newsom “the great uniter” because “a very diverse group of people” support the recall.

Newsom approval plummeting with a third of voters support recall amid COVID-19 criticism, poll finds

More than a third of the state’s registered voters said they would vote to oust Newsom from office if the recall qualified for the ballot, though 45% said they would oppose such a move, a Berkeley IGS poll found.

“Maybe the cardinal failure of our political system in California for a long time is that it leaves people feeling powerless and disenfranchised with so much of our lives and governance dictated from afar,” he said.

After Newsom’s stay-at-home order took effect last March, sales at Zephyr Books & Coffee tumbled more than 30%. The Scotts laid off all six employees. They kept the store open and ran it by themselves.

“We invested in the store. All of our time. Most of our resources. We have to make it work,” Guy Scott said.

By July, as business picked up again, the Scotts had hired everyone back. At the time, Siskiyou County — home to 43,500 people in a space eight times larger than Orange County — had confirmed fewer than 75 COVID-19 cases.

Zephyr Books & Coffee, named after the Scotts’ grandson, opened in this town of 7,500 people in 2016.

“We found ourselves making friends and building bridges with people we had nothing in common with in our normal life,” Guy said. “But in the store, we’re like, ‘Hey, come on in.’ We met people and became friends with people that we are completely different from, red and blue.”

Yet tensions surfaced over the last year. The couple never required customers or employees to wear masks. It drove some away. It attracted others.

To the Scotts, the governor’s executive orders and mask mandate were tantamount to suggestions, since they were not approved by the California Legislature.

But “really, the biggest turn in our attitude toward the coronavirus and the regulations was when [Newsom] went to dinner at the French Laundry,” Debbie said of the governor’s infamous maskless outing just before Thanksgiving. “Everything changed. We went, ‘Bye-bye. We’re all done.’”

If the recall campaign’s results hold steady from last month — when state officials reported that almost 84% of the initial signatures were valid — there would be more than enough signatures for an election that could oust Newsom.

They hung a sign on the front door saying recall petitions were inside. One customer stopped coming in because he was so mad — but he couldn’t find good muffins anywhere else, so he came back, Debbie said.

“Fences have been mended,” she said, laughing.

Seven miles east, in the tiny town of Montague, Tressa Bowen, 73, said scores of signatures had been collected at Cortright’s Market & Deli, where she is a longtime cashier. Newsom, she said, “is costing us money.”

“It was everybody down south that voted for him, not us,” Bowen said. “They don’t know anything about ranching. They don’t know anything about incomes up here. It’s like they’re punishing us up here.”

Siskiyou County, which has recorded 1,826 COVID-19 cases and 14 deaths over the last year, has been in the most restrictive purple tier of the state’s four-phase reopening guidelines since November. There were 34 active cases as of Thursday, according to county officials.

“Even as a motivated student, a varsity athlete, I’m struggling.”

— Ceiba Cummings, an 18-year-old senior at Yreka High School, who believes rural counties have been held to unfair standards

Ceiba Cummings, an 18-year-old senior at Yreka High School who is planning to register to vote soon, said she would support the recall because she believes rural counties have been held to unfair standards and that school closures have been harmful.

After schools shut down last spring, Cummings, who teaches rock climbing at the YMCA, oversaw a group of children between the ages of 5 and 12 who spent all day at the facility because their parents had to work. She tried to help a frustrated kindergartner learn how to read and watched despairingly as the kids watched cartoons on their tablets.

Students at her high school are now doing hybrid learning, spending half their time on campus and half learning online.

“I’m a senior and I’m salutatorian right now, and my motivation has gone from being the top of my class to now I’m struggling to keep up, even with going half on campus, half off campus,” Cummings said. “Even as a motivated student, a varsity athlete, I’m struggling.”

Cummings, who moved to Yreka her freshman year, said she and her family have always been liberal. But living in a conservative town has made her consider all perspectives.

In January, she wrote a letter to Newsom.

“It is difficult for me to say I am pleased or agree with the way COVID-19 measures have been enacted here,” she wrote. “I am not able to attend school regularly with the rest of my class, but facilities like Wal-Mart and fast food restaurants remain business as normal, but all of our LOCAL small town businesses and restaurants have been STRUGGLING immensely.”

State elections officials said last month that they had verified 3,299 signatures supporting the recall from Siskiyou County turned in by Feb. 5 — about 10% of the county’s residents ages 18 and over, one of the highest percentages of any county.

Here, residents have long wanted to carve a separate State of Jefferson out of California’s conservative northern counties. Many fly the green Jefferson flag with its pair of X’s, called a “double cross,” that represent a sense of rural abandonment.

In November 1941, Yreka, a Gold Rush town about 20 miles south of the Oregon border, was declared the capital of the proposed breakaway state. Armed residents — hoping to draw attention to deteriorating roads they deemed “not passable, hardly jackassable” — set up roadblocks along Highway 99 and handed out proclamations saying they would secede every Thursday until further notice. The movement was halted when Pearl Harbor was bombed.

Mark Baird, a Siskiyou County rancher whom many see as the father of the modern Jefferson movement, said Newsom chose winners and losers in the pandemic by declaring businesses essential or nonessential.

He and his wife own FM country radio station KSYC and the classic rock station KHWA. Although they were essential because they provide emergency alerts, their advertising dollars dried up as other businesses closed. Baird said KHWA is no longer transmitting and that he is considering selling the stations.

“I’ve had them about 10 years and have my life savings in them,” Baird said. “I’m almost 70. I doubt California’s going to replace the money we invested.”

Newsom “usurped authority that didn’t belong to him,” Baird said. “When you elect a king, don’t be surprised when he acts like one. If we want liberty, we have to vote like it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.