Why your place in the COVID-19 vaccine line depends on where you live

When the first doses of COVID-19 vaccines were rolled out in the United States, the choice of who should receive them was fairly obvious — and widely accepted.

They would go to healthcare workers, who are highly exposed to the coronavirus and keep the medical system functioning, and people living in nursing homes, who have made up a third of all COVID-19 deaths nationwide.

Since then, the choices have gotten tougher: Teachers, farmworkers, senior citizens and dozens of other groups have made compelling arguments for why they should go next. For leaders making those decisions, it is effectively a zero-sum game: giving priority to some means fewer doses for others.

Though the nation’s vaccine availability will probably improve substantially in the coming months, officials at this moment are wading through what could be the most contentious phase of the rollout — a collision of relentless demand and constrained supply.

“We’ve got to take care of the most vulnerable,” Gov. Gavin Newsom said at a recent news briefing when asked about priority for individuals with disabilities and underlying conditions. “I’m committed to do that, but I fear that whatever we do won’t be enough until supply is adequate.”

Desperate attempts to fairly distribute the scant supply have created 48 different vaccine eligibility lists across 50 states, with some giving early access to incarcerated people, hospitalized psychiatric patients or people living in multi-generational households, according to data collected by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

In California, there are as many as 61 more vaccine priority lists, as local health departments are allowed to deviate from Newsom’s rules as they deem appropriate.

“When you get your place in line really ends up depending on where you live,” said Jennifer Tolbert, an author of the Kaiser foundation report. “There honestly are no good decisions when you’re in a situation of so many people needing the vaccine, and just not enough doses.”

There’s still a risk if one person has been vaccinated against COVID-19 and another person hasn’t been, experts say.

At the heart of the debate around how to allocate vaccines is a conundrum: Should scarce vaccine be given to one young person, say a supermarket cashier who interacts with hundreds of people a day, because that may protect five elderly people from being infected? Or should the vaccines go directly to five elderly people?

Leading public health experts disagree about how to answer that question. Yet state and local officials face the daunting task of providing a solution that balances science and politics in a way that is equitable and practical.

The nation’s vaccine supply may be abundant in a few months, but for now, when there are only so many lifeboats to go around, some people are bound to be harmed by being left onboard.

“I so regret having to think about it as an either-or,” said Dr. Eve Glazier, president of the Faculty Practice Group at UCLA Health.

::

In December, as the U.S. vaccination rollout began, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released recommendations for how states should allocate the doses.

They advised vaccinating healthcare workers and long-term care facility residents first. Thirty states followed the guidance exactly, while the others tweaked it by adding police, teachers and other groups.

Next the CDC recommended vaccinating people 75 and over and front-line essential workers, such as grocery store workers, postal workers and teachers. But as states prepared for those vaccinations, federal officials on Jan. 12 called on them to immediately offer shots to everyone 65 and above.

“That as much as anything explains why there is so much variation,” Tolbert said.

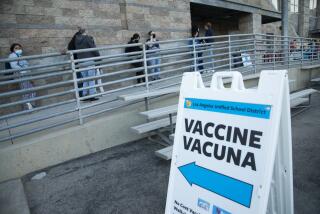

Many states, including California, soon expanded access to vaccines to all seniors, a move that came at the expense of essential workers who were supposed to be next in line. In L.A. County, vaccinations for teachers, grocery store workers and law enforcement will not begin until Monday, though people 65 and older have been able to make vaccination appointments for weeks.

Tolbert said that the push to expand vaccinations to people 65 and older was probably an attempt to speed up the slow rollout, since it is simpler to verify age than job status.

And it may be a reflection of where the country was in January — in the midst of a devastating and deadly COVID-19 surge. Protecting people most likely to die from COVID-19 felt particularly urgent, she said.

But unpredictable vaccine allotments have prevented states from moving on to the next tiers as quickly as they may have hoped. California has received just three-quarters of the vaccine doses that officials initially expected by the end of February and has fully immunized less than 6% of its population.

The CDC had a strong argument for wanting to vaccinate essential workers quickly, some experts say. Though counterintuitive, vaccinating people who may be healthier but more likely to spread the disease can better curb transmission than vaccinating those most likely to die, experts say.

Though the vaccine trials found that the shots significantly reduce deaths and hospitalizations, scientists are studying whether the vaccines reduce transmission of the virus as well. Many experts believe they do.

In an analysis released this month, Rand Corp. researchers found that vaccinating the 15% of the population that has the fewest contacts, such as the elderly who mostly stay home, reduced new infections in a society by 1%, compared to a 96% reduction in infections following a vaccination plan that targeted the 15% of the population with the most contacts, such as essential workers.

“This strategy has the potential to reduce the spread of the virus so radically that everyone, including the vulnerable, will be safer,” the Rand researchers wrote. “People should be vaccinated not so much to protect them, but to protect others from them.”

Essential workers also face serious risks from COVID-19, experts say. California food and agriculture workers under 65 experienced a 39% increase in mortality during the pandemic compared to before, according to a UCSF study.

“We’re talking about people that cannot afford to stay home,” said Esther Bejarano, a community health worker in Imperial County. “You cannot compare vulnerability just solely based on age.”

People under 65 make up the majority of people hospitalized with COVID-19 nationwide, said UC San Francisco epidemiologist Dr. Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, a co-author of the study. And when analyzing COVID-19 deaths among people who don’t live in nursing homes, approximately one-third are people under 65, many of whom are essential workers, she said.

Removing groups of essential workers from the vaccine priority list also worsens racial inequities in vaccine distribution, since many are people of color, and will allow outbreaks to continue in the hardest-hit neighborhoods, she said. In L.A. County, vaccination rates are lowest in communities hardest hit by the virus, early data shows.

Vaccinating only on the basis of age “doesn’t help to get the pandemic under control,” Bibbins-Domingo said. “The strategy at some point has got to be to try to break chains of transmission, and that is in these very same communities.”

The calculus on how to best distribute the doses will probably continue to evolve as more vaccine supply becomes available. The FDA is expected to approve the one-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine within the next few days.

Tuesday was the second-busiest day at city-run vaccination sites, L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti said, and doses are expected to improve in coming weeks.

Ideally, the vaccination strategy would eventually shift from protecting people at risk of death to reducing transmission, though when that turn comes will be based on vaccine supply and a state’s demographics, said Harvard internal medicine physician Dr. Abraar Karan.

“There comes a point at which it makes more sense to vaccinate people that have a higher exposure and that have a higher chance of transmitting onwards and superspreading than it does to get 100% of high-risk people that are in their 70s or 80s,” he said. “To me, it’s not clear when that point is.”

For now, the national patchwork of policies doesn’t make much sense and increases skepticism among the public that rules aren’t based on science, said Yale sociologist and physician Dr. Nicholas Christakis. For many weeks, for example, anyone over 65 years old was allowed to make a vaccine appointment in L.A. County, while vaccination was open only to people over 75 in neighboring Ventura County.

“I wish we had a consistent national policy,” he said. “It’s a little bit like designating one part of the swimming pool for urination and hoping for the best.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.