Column: We’ve quit ringing the bells each night, but front-line workers are still risking their lives

- Share via

It took a while for Ana Ivette Zacarias, 25, to figure out what she wanted to do for a living.

As a teenager, she went to flight attendant school in Guatemala, but then her family moved to Los Angeles, and she got a job at a restaurant while attending Roosevelt High School in Boyle Heights. Later, she sold used cars at a dealership.

For the record:

11:22 p.m. Dec. 5, 2020A previous version of this story said the clinic’s typical doctor-assistant ratio of 2 to 1 had fallen closer to 1 to 1. It was the assistant-to-doctor ratio that fell from 2 to 1.

But Zacarias never forgot how helpless she felt years ago, when her grandmother suffered through dementia. And two years ago, she watched her own young son labor through a serious case of pneumonia.

That’s when Zacarias knew she wanted to work in healthcare. So much so that she juggled work, family and vocational school simultaneously to become a certified medical assistant.

This year, she applied for work and heard back from several medical facilities. But the one that felt like the best fit was a clinic in her own neighborhood.

The South Central Family Health Center, at 44th Street and Central Avenue, has made a point for nearly 40 years of putting its neighbors to work at its nine different community locations. And the main office is just several blocks from the home Zacarias shares with her father, two brothers, husband and their two children, 4 and 2.

“I feel comfortable working here because I know the people, and the patients are not just our patients, they’re our neighbors,” Zacarias said.

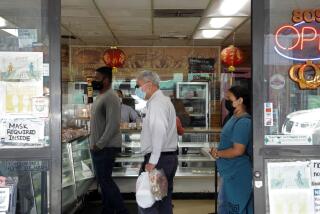

On Thursday morning, Zacarias wore a gown, mask and goggles as she checked in a steady stream of patients in the center’s parking garage.

Why the garage?

Because if the virus is in the air, it can more easily escape a well-ventilated area.

Zacarias begins setting up the makeshift clinic at 7:30 each morning, arranging equipment and testing stations and sanitizing everything with spray and wipes. She screens patients for symptoms, checks their vitals and draws blood to be tested for COVID-19 antibodies. One day, she told me, when she can squeeze in the time, she wants to begin studying to become a registered nurse.

The doctor she works with, Grace Neuman, performs the nasal swab tests and hands the samples to Zacarias for proper labeling. Neuman speaks Cantonese, which isn’t often useful at this clinic, but she’s learning Spanish on the job, with Zacarias interpreting as needed. After months of working together, they’re in sync.

“She’s like my right hand,” said Neuman, who is able to communicate with her assistant despite the encumbrance of protective gear. “We can just make eye contact and know instantly what it means.”

Neuman, like Zacarias, grew up with working-class parents — an auto mechanic and a postal worker — in San Francisco’s Mission District. Also like Zacarias, she wanted to work in a community where the need was great, and the pandemic has only deepened her sense of duty, because areas like South L.A. have been hit disproportionately hard.

“Being a human first, the fear is definitely there,” Neuman said. “But it’s tempered with the knowledge that I’m in the right place at the right time.”

Many of the patients she and Zacarias see are the working poor, and the doors to the clinic are open to them whether they can afford health insurance or not. They work in restaurants and warehouses; they’re delivery drivers and gardeners, housekeepers and construction workers.

“These are the front-line people who keep our economy going,” said David Roman, the center’s director of development and communications.

The vast majority of patients at the health center’s nine locations are Latino, many live in multi-generational homes, and many have preexisting conditions such as diabetes, asthma and hypertension, any of which raise the risk of death from COVID-19. At the end of a workday, which for many patients includes exposure to the virus, Roman said, those who don’t have washers and dryers to sanitize their clothes at home end up congregating at laundromats, further raising the risk.

Roman said roughly 12% of the nearly 8,000 coronavirus tests administered by the health center since May have come back positive. And that means danger for health workers like Zacarias and Neuman.

On a staff of 223, said Roman, “we’ve had 46 positive tests for COVID-19, and we had a pediatrician test positive this week.”

So many medical assistants have tested positive that the typical assistant-to-doctor ratio of 2 to 1 is now closer to 1 to 1, Roman said.

Zacarias, who has not gotten sick since beginning her job in July, told me she is extra careful and always masked, at work and at home. She said she’s certainly aware of the risk, having seen patients with advanced symptoms on a daily basis, but she’s undeterred. The suffering and fear, Zacarias said, “make me feel brave, and happy that I’m able to help people.”

By 9 a.m. Thursday, Neuman had already sent two patients to the hospital with severe symptoms that appeared COVID-related. In the first wave of cases this year, as many as 100 coronavirus tests were performed daily, then the number gradually dipped to 20 or fewer.

But there was an uptick when the weather cooled, and the number of tests climbed above 30 Thursday, in what might be the beginning of a post-Thanksgiving surge. Juan Ramos, another medical assistant, joined the Neuman-Zacarias team for the day to help with the extra load.

“I’m feeling a little sick and I have a cough,” said patient Mireya Armijo, a restaurant worker whose husband is a bus driver.

Santiago Gomez and Cirila Samano, who work as housekeepers, know people who have gotten sick, and they came in for tests because Gomez was bothered by body pains and a headache.

Another couple, who work in a warehouse, said they felt OK but wanted a test because they’re exposed to so many other people at work. And an elderly man in a wheelchair came for a test because he had flu-like symptoms along with preexisting lung disease.

Some patients come in because they’re ordered to by employers, and Zacarias said she’s encountered a few who think the virus is a hoax, or that they’re somehow immune. She straightens them out in a hurry.

“I tell them to try to be a little more respectful of others, and do it for your family,” Zacarias said.

At the end of her shift, Zacarias trashes her protective gown and changes clothes before picking up her kids from a baby-sitter. Everyone in her house works, except for one brother who’s a student, so Zacarias makes sure everyone follows COVID safety rules in and out of the home.

“People ask me if I’m afraid to go to work,” Zacarias said. “But I’m not afraid. I feel blessed, and it is good to hear people say thank you for being there.”

We used to say thanks a little more regularly early in the pandemic, by ringing bells, blowing horns and clanging pots and pans at 8 o’clock every evening. I don’t know why we can’t strike up that band again, even louder this time, not just for doctors and nurses but for all their assistants too.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.