The death of a newborn named Boaz Yoder in an Altadena apartment seemed at first glance like a case of sudden infant death syndrome.

His mother told investigators she had put the baby boy to sleep under blankets on a chilly autumn night in 2017 and found him the next morning lifeless in his crib.

The closer investigators from the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department’s Homicide Bureau looked, however, the more doubts they had.

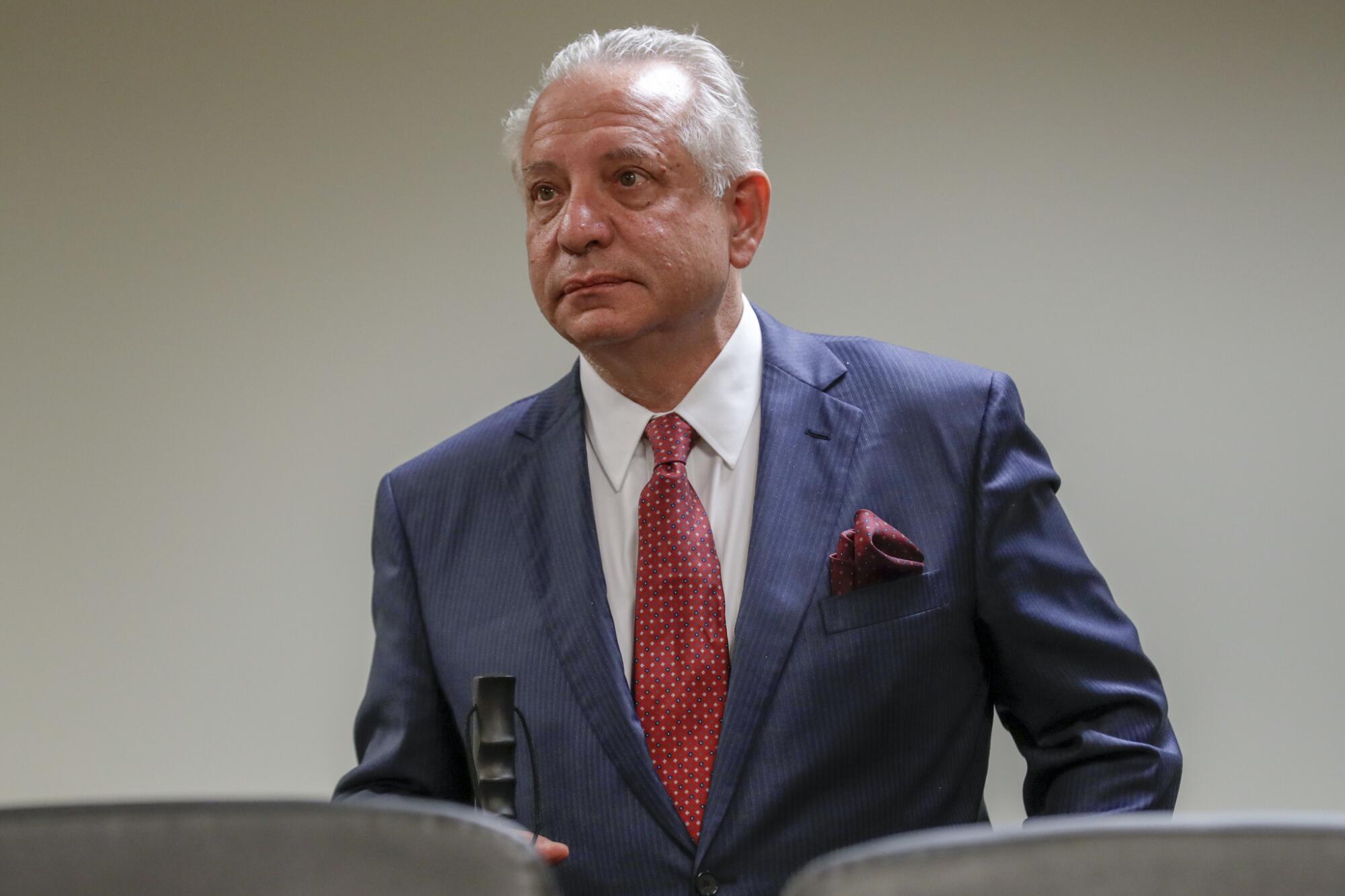

The search for the truth plunged Dets. Mike Davis and Gene Morse into a murky world of desperate young addicts and small-time drug dealers with a disgraced multimillionaire at the center: Dr. Carmen Puliafito, former dean of USC’s Keck School of Medicine.

For 2½ years, the detectives and a child-abuse prosecutor circled Puliafito and the baby’s mother, a hairdresser and former nude model. They turned up evidence in County Jail, a toxicology lab and the confidential files of USC’s white-shoe attorneys. What they found was shocking, infuriating and devastatingly sad, but in the end, only one thing mattered: Was it enough for criminal charges?

Homicide investigations are rarely easy or quick, but Boaz’s case is notable for the time and resources that law enforcement committed as they sought justice. It’s a case that demonstrates the challenges of child-death investigations and the particular complications of a wealthy and connected suspect — in this case, a world-renowned physician with a legal team and private investigator at his disposal.

Puliafito and his attorney said he had done nothing wrong.

***

‘He was just found like this by his parents?’

— 911 emergency dispatcher

By the time Davis and Morse got to the duplex on Alameda Street, the paramedics had come and gone, and the coroner’s office was preparing to take Boaz’s body to the morgue for an autopsy.

Though assigned to the homicide unit, Davis and Morse sometimes were dispatched to accidents, suicides or other sudden deaths that, in the end, weren’t found to be criminal in nature.

The scene they encountered Oct. 5, 2017, had the hallmarks of one of those cases: a tragedy, but not a felony.

There was no immediate indication of abuse or neglect. Boaz weighed 10 pounds and was carefully dressed in a blue-and-white onesie and matching socks, according to a report by the coroner’s investigator.

The apartment was neat and clean and filled with “good baby equipment,” Davis recalled in an interview.

“There was nothing out of the ordinary there,” he said.

The baby’s mother, a winsome, blond 26-year-old named Dora Yoder, “seemed really distraught,” Davis recalled.

“My heart went out to her,” he said.

She told the investigator that she last saw her son alive about 2 a.m., when she nursed him. The temperature outside had dipped to 55 degrees; she said the heater inside the apartment wasn’t working, and “it felt like the air conditioner was on instead,” according to the investigator’s report.

Yoder recalled putting extra clothing on Boaz, then piling blankets on top of his chest: two muslin, then a woolen one, followed by a crocheted blanket and a queen-size gray quilt that one detective estimated at 4 to 5 pounds.

Yoder said she woke just before 7:30 a.m. to find the boy “unresponsive,” the report states. The blankets, she said, were not covering his face.

She said she immediately called Ariel Franko, the child’s father. Franko, a felon described in a police report that year as a daily user of methamphetamine and heroin, lived about 20 miles away in Sherman Oaks with his parents. The report does not address why Yoder called him before summoning an ambulance, and she did not respond to messages seeking comment.

Yoder told the investigator that she asked Franko “what to do because she didn’t know CPR.” He told her to use a mirror to check for breathing. “When she could not see breaths, he advised her to call 911,” the report said.

Yoder claimed she phoned for an ambulance at 7:30 a.m. Law enforcement records do not reflect such a call.

Instead, it was a male caller who dialed 911 at 7:40 a.m. to report a baby who wasn’t breathing. He said that the mother was his girlfriend but that he was in Pasadena.

“He was just found like this by his parents?” the emergency dispatcher asked. “I don’t know. She called me crying,” he replied.

When she spoke with the coroner’s investigator at the scene, Yoder did not mention contacting a man in Pasadena for help, according to the investigator’s report.

Only later would detectives learn that the caller was Puliafito and that the physician, who was 66 at the time, played an outsize role in Yoder’s life. The apartment lease was in his name, and her family and friends suspected he paid for almost everything: furniture, groceries, baby supplies and, disturbingly, drugs.

The man who called for an ambulance at an Altadena apartment last fall had the calm and direct manner of one familiar with healthcare emergencies.

***

‘He gives my daughter money and he pays for her rent, and he pays for all that stuff.’

— Menno Yoder, Dora Yoder’s father

The detectives soon discovered that Yoder and Puliafito had been on the Sheriff’s Department’s radar well before Boaz’s death.

A year earlier, Yoder’s father had phoned the department’s Altadena station from his Missouri home and shared worries about Puliafito’s influence.

“My daughter’s been known to do drugs, and she’s involved with a doctor that’s also been known to do drugs,” Menno Yoder told a deputy on Aug. 30, 2016, according to a recording of the call. “He gives my daughter money, and he pays for her rent, and he pays for all that stuff.”

At the time, Puliafito had a sterling reputation in ophthalmology and lived in a $5-million mansion with his wife of 38 years.

Few knew, though, that he led a double life. He was in an intense relationship with a 21-year-old escort named Sarah Warren, lavishing her with more than $300,000 in gifts and living expenses, according to an accounting he later provided a judge. His largesse included funding Warren’s drug habit, she later wrote in a sworn affidavit.

Puliafito started using heroin and methamphetamine, he later admitted in court testimony, and was often in the company of a younger crowd that included Yoder and Franko. He became increasingly erratic at work and, under pressure from USC, resigned as dean in March 2016.

In USC’s lecture halls, labs and executive offices, Dr. Carmen A. Puliafito was a towering figure.

Warren got clean later that year and cut ties with Puliafito. Yoder, who had long struggled with heroin addiction, subsequently assumed a more central role in his life. In early 2017, she turned to him after discovering she was pregnant, and he paid for her detox program, according to medical board filings.

Theirs was a curious relationship. Four decades separated them. Puliafito had three Ivy League diplomas. Yoder had grown up Amish and did not have a college degree. He has insisted they were never romantic partners. But he clearly doted on her. During her pregnancy, he took her on trips to Hawaii and Israel, he later testified. In emails between them that were reviewed by The Times, he wrote that he loved her, and she described his interest in helping her as “sexy.” He was a regular presence at her home.

Puliafito spent a month in rehab after being ousted from USC but remained deeply involved with Yoder, according to medical board filings and her relatives.

The University of Southern California paid Dr.

Boaz was born Sept. 10, 2017. It seemed to Yoder’s family that things were finally going well.

Then, in mid-October, she told them Boaz had died of SIDS. In a text to family members reviewed by The Times, she wrote that her loss was too painful to discuss. She offered her family a timeline, and it differed in one way from the one she’d outlined to police: She said she found Boaz dead at 6 a.m., not 7:29 a.m., leaving an unexplained hour-and-a-half window before Puliafito’s 911 call.

Her relatives were shocked by the child’s death and then suspicious. They called the Sheriff’s Department, reiterated their concerns about Puliafito and encouraged investigators to look closer at Boaz’s death. One of Yoder’s sisters later met with detectives.

***

‘Every time you would interview one person, they would mention another person in this little world.’

— Det. Mike Davis

To find out how the baby died, detectives set out to understand how his mother and Puliafito lived. They found a map to that world in the County Jail’s pay phones.

Though Puliafito had never been charged with a crime, the addicts and dealers he partied with were arrested with some frequency, court records show.

Jail authorities recorded inmate calls, though getting incriminating information was generally a long shot, since every call included an automated warning that conversations were taped. But Davis and Morse requested access to calls placed from jail to the cellphone numbers of Puliafito, Yoder and the baby’s father, Franko, anyway.

They obtained about a hundred recordings, including more than a dozen to Puliafito’s phone in the period around the baby’s death, according to Davis and a transcript of a medical board hearing. In that period, Puliafito talked three times to Franko, who was himself in and out of jail on drug-related charges, according to the testimony. The physician also had multiple conversations with Kyle Voigt, a convicted dealer who had partied with both parents and was on his way to prison, the transcript indicates.

Puliafito spoke openly with the jailed men about illicit substances, associates who overdosed and young female addicts in their circle, a lawyer for the board told a judge at the hearing.

When detectives heard an unfamiliar name on the recordings, they tried to track the person down.

“Every time you would interview one person, they would mention another person in this little world,” Davis said.

Read more about Dr. Carmen Puliafito, former dean of USC’s Keck School of Medicine.

As is the norm for homicide detectives, the pair were responsible for more than a dozen investigations at any given time. To stay on top of the voluminous calls in the Yoder case, Davis took to playing the jail recordings in his car as he drove home.

The detectives listened closely for information about Boaz.

“There was conversation about the child’s death,” Davis said, declining to elaborate.

Another resource for detectives was a confidential report about Puliafito’s misconduct prepared for USC’s trustees by former U.S. Atty. Debra Wong Yang and her firm, Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher. The university had long refused to make the report public, but detectives obtained a warrant and, eventually, some of the report.

Detectives went to Puliafito’s home, but he declined to talk and referred them to a criminal defense attorney.

They later learned that a private investigator and another person working on the doctor’s behalf had contacted members of the Yoder family, according to interviews and documents reviewed by The Times. Family members received prewritten affidavits to sign containing explicit denials that Puliafito used drugs as well as denials that Yoder harmed the baby. It’s unclear whether any signed.

As detectives worked, a blood sample taken from Boaz’s heart awaited testing in the lab of the L.A. County medical examiner-coroner. Two months after the infant’s death, a toxicology screen detected methamphetamine.

The presence of the drug in the breastfeeding baby’s system was a pivotal development. It provided proof that more had been going on in the Altadena home when Boaz died than Yoder had let on.

When detectives went to interview Yoder again, they found Puliafito’s red BMW parked outside her apartment. As they approached, the doctor spotted them and left, Davis said. Yoder “wasn’t real receptive,” the detective recalled, but agreed to a brief interview in the driveway.

She admitted “to using methamphetamine twice since giving birth and one time being the night before the infant died,” according to an email by the coroner’s investigator. It’s unclear what, if anything, she said about Puliafito.

What is clear is that the totality of evidence Morse and Davis gathered prompted a prosecutor to mull an involuntary manslaughter case against Puliafito and a child neglect charge against Yoder, according to a memo by the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office.

“It is suspected that Puliafito provided Yoder methamphetamine, which they both allegedly used” the night before the baby was found dead, according to the memo by Deputy Dist. Atty. Jon Hatami. The specialist in child-death prosecutions, who led the case against the killers of Gabriel Fernandez, wrote: “Later on, Yoder breastfed the victim. … In the morning … both suspects discovered that the victim had died. Puliafito left Yoder’s home before he called 911 to report the baby was not breathing.”

After being informed of what the prosecutor wrote, Puliafito told The Times in an interview that it was “absolutely not true.”

He acknowledged going to the apartment the night before “to see the baby” but said he “observed no drug use.” He insisted he was at home with his wife in Pasadena when Yoder called him in a panic.

“My first instinct was to call 911,” he said. He drove over to her apartment, but “it was swarming with EMTs.” He did not stop.

***

‘He perjured himself on the stand here today.’

— a state prosecutor representing the medical board

As the detectives worked, Puliafito was fighting efforts by the state medical board to take his license. He was, his lawyer noted, “one of the foremost ophthalmologists in the world.” The physician, whose license was suspended in September 2017, promised that if he was allowed to practice again, he would devote himself to treating the underserved Latino population in East L.A.

On the witness stand at a hearing in June 2018, nine months after Boaz’s death, Puliafito portrayed himself as completely rehabilitated and said he hadn’t used drugs in almost a year.

An attorney representing former USC medical school dean Carmen Puliafito acknowledged at a state medical board hearing Wednesday that the physician used hard drugs while employed by the university, but argued that the doctor has been in recovery for months and should be allowed to practice medicine.

A state prosecutor representing the medical board zeroed in on his relationship with Yoder.

“She’s a known drug user, right?” Deputy Atty. Gen. Rebecca Smith asked.

“I don’t know what her current status is,” he answered.

“But you have used with her, correct?” Smith continued.

“No, I have not,” he replied.

He initially said he had no firsthand knowledge of Yoder’s drug use but later acknowledged her previous heroin addiction. Their relationship was not sexual, he testified.

Rather than a “sugar daddy,” his role was “healthcare consultant.”

“As a practicing Catholic, if someone comes to me and says, ‘I’m interested in saving the life of my unborn baby,’ I was sympathetic,” Puliafito told the judge.

He claimed in his testimony that he was no longer in close touch with Yoder and had cut off contact with other members of his drug-using circle.

Puliafito did not know that the homicide detectives had been monitoring his jail calls or that Smith, the prosecutor cross-examining him, had copies of the recordings. She asked him when he had last communicated with Franko.

“More than two years ago,” he said.

The prosecutor asked about others — Voigt, the dealer in jail; an addict named Ashley; a Santa Monica heroin user named Nicole. Puliafito denied an ongoing relationship with Voigt and said he had never heard of the women.

After Puliafito left the witness chair, Smith revealed the existence of the jail recordings that proved he was in close contact with Voigt and Franko and knew the female addicts.

“He perjured himself on the stand here today,” the prosecutor declared.

She did not refer Puliafito for prosecution, but he did not get his medical license back.

The state agency that regulates physicians on Friday ordered USC’s former medical school dean stripped of his license to practice medicine, citing “an appalling lack of judgment” in his use of drugs and association with a circle of addicts and criminals while leading the major institution.

***

‘There are a lot of unanswered questions about this death.’

— Dr. James Ribe, a specialist in pediatric autopsies

The last stop for the investigation was the coroner’s office on Mission Road.

An autopsy of the infant by Deputy Medical Examiner Dr. Linda Szymanski found minor lung congestion, pinpoint hemorrhages on the heart and a healing burn on the left hand, but nothing definitive as to why he died.

The toxicological report was similarly inconclusive.

The methamphetamine level — 50 nanograms per milliliter — was “not super high,” said UC San Francisco-Fresno medical toxicologist Dr. Patil Armenian, a drug researcher and emergency room doctor who reviewed the coroner’s report for The Times. She cautioned that there was little research on what constitutes a lethal dose for a baby. In one of the few studies, a review of eight newborns who died with the drug in their systems, “the ones clearly due to meth were a little bit higher level” than that of Boaz, Armenian said.

Still, she noted, “no meth should be present in an infant.”

Szymanski, who now works at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, declined to discuss her work.

Emails obtained through a public records request show that she and her supervisor initially decided it was not possible to determine how Boaz died. Later that week, Szymanski learned from the coroner’s investigator about Puliafito’s involvement and the attendant interest in the case from The Times. She asked for a meeting with the head coroner, Dr. Jonathan Lucas.

“I just want to confirm that Dr. Lucas is in agreement with my cause and manner of death as this case has media interest and I can foresee it landing in a Los Angeles newspaper,” Szymanski wrote in an email.

She and Lucas met. Afterward, she changed her conclusions. The report she filed listed the cause of death as asphyxiation from blankets on the baby’s chest, with “methamphetamine exposure” from breast milk listed as a contributing condition “not related to the immediate cause of death.”

She next had to rule on the manner of death — accident, natural, suicide, homicide or undetermined. She checked a box indicating “accident.”

Three medical experts The Times consulted said they disagreed with aspects of her report, starting with the manner of death. They said that although they did not see evidence of foul play in reviewing the baby’s autopsy, they also did not see conclusive evidence of an accident and disagreed with the decision to classify the death that way.

“There are a lot of unanswered questions about this death,” said Dr. James Ribe, a specialist in pediatric autopsies who retired from the L.A. County coroner’s office in 2018.

Because physical evidence of asphyxiation is often absent, it is common to rely on circumstantial evidence, including witness accounts, to arrive at a conclusion.

Former L.A. coroner’s investigator Denise Bertone, a nurse who performed more than 2,000 pediatric death investigations, said she doubted whether Yoder was credible enough to inform the coroner’s determination.

“You don’t base a diagnosis of asphyxia solely on the report of the mother when she was high at the time she placed the baby to sleep,” Bertone said.

Bertone is currently pursuing a whistleblower lawsuit against the office for its handling of another child-death investigation.

Discolorations on the baby’s chest and face also cast doubt on Yoder’s version of events, four experts said. The marks are evidence of blood pooling after death, they said, and suggest Boaz could have died on his stomach and was flipped over sometime later.

A coroner’s spokeswoman acknowledged that the marks could be evidence of a face-down death but said they were “consistent” with blanket suffocation.

Three experts found the burn on the baby’s hand to be suspicious. Yoder told investigators that, the week before he died, the then-18-day-old infant reached his hand out of a baby wrap and touched a hot pan. Yoder said she went to a pediatrician the next day, a visit the coroner confirmed.

Ribe, the retired pathologist, said the wound’s severity indicated a hot object was probably against the child’s hand long enough — or with sufficient pressure — to burn through the skin.

“The burn is from more than just touching something hot,” said Ribe, who assigned the case to Szymanski but did not recall being involved in its conclusions. He cautioned that his opinion was based on the written report, not the photos of the injury.

Investigators enlisted another pathologist to weigh in, and emails show that, as recently as May, one of the detectives sought to meet and discuss the case with the head coroner. A child-abuse expert was also consulted. In the end, the coroner’s office stuck with its findings. Lucas, the head coroner, reiterated confidence in Szymanski in an email to The Times this month.

“Determining the cause and manner of death is a matter of professional judgment,” he said.

The official finding that Boaz was suffocated accidentally by a pile of blankets presented a challenge to the district attorney’s office.

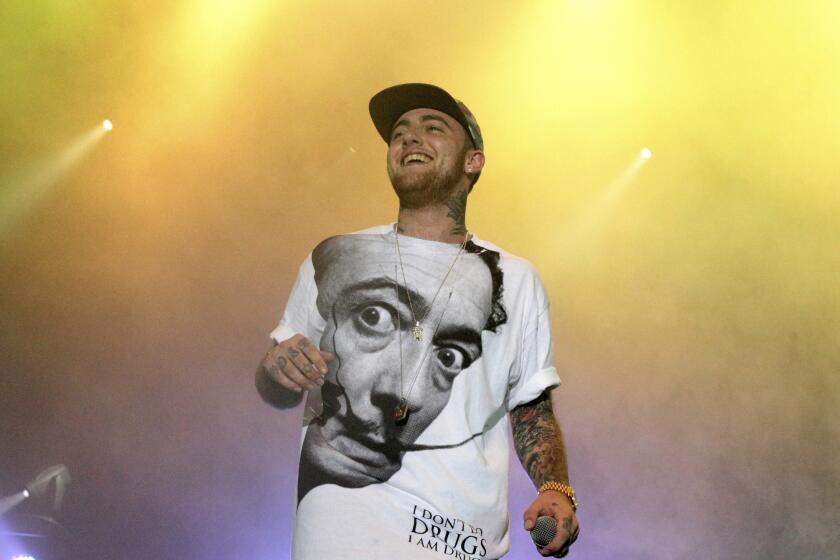

Law enforcement is increasingly targeting people who provide illegal drugs that cause overdoses. Federal grand juries in L.A., for example, indicted three men last year on charges of providing the drugs that killed rapper Mac Miller and charged activist Ed Buck in two overdose deaths.

Ed Buck, who was indicted last year in connection with the overdose deaths of two Black men in his West Hollywood apartment, now faces four additional charges.

Prosecutors elsewhere have gone after parents in the deaths of babies that were blamed on drugs.

A Shasta County woman suspected of nursing her newborn while using methamphetamine and heroin is serving a life sentence following a conviction of first-degree murder by poisoning. Her baby’s father, who was suspected of procuring drugs for her, among other offenses, received a sentence of 18 years.

A grand jury indictment accuses three men of providing cocaine and oxycodone pills laced with fentanyl that caused rapper Mac Miller’s death in 2018.

In those cases, however, drugs were the clear-cut cause of death.

Without that, the prosecutor and the detectives concluded they could not take the investigation further.

“That finished it for us,” Davis said.

The district attorney’s office declined to comment and did not make Hatami, the prosecutor, available for an interview.

Hatami wrote in a June 23 memo: “After a thorough investigation and consultation with medical experts … there is insufficient evidence to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the victim died as a result of a crime by either suspect.”

No one appears to have informed Puliafito, Yoder or her family about the decision not to prosecute. Her sister Miriam Jones reacted angrily: “I know he’s responsible for this baby’s death, indirectly or directly.”

Puliafito’s lawyer, Timothy Reuben, insisted in an email that despite the law enforcement findings, the physician “was simply a good Samaritan.”

“Dr. Puliafito did NOT provide any methamphetamine to Dora Yoder nor was he using any,” Reuben wrote.

Yoder gave birth last year to a second child, a girl, with Franko, according to birth records. Her landlord said Puliafito continued to pay the rent at the Altadena apartment and was a frequent visitor there.

By Davis’ estimation, the Yoder case took more detective work than 90% of his other investigations, including those that ended with convictions.

Still, he said, “I feel we did our part.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.