When Americans go missing in Mexico, U.S. officials have to tell loved ones, ‘Go to Mexico’

- Share via

ROSARITO, Mexico — When Karla Izquierdo’s ex-husband, Francisco Aguilar, disappeared in Rosarito, she unwillingly joined a group no one wants to become a member of: the tens of thousands of families searching across Mexico for their missing loved ones.

But, in one sense, the case is a relative rarity because Aguilar, a 20-year veteran of the Los Angeles Fire Department, is an American citizen.

Each year, millions of Americans visit Mexico without incident. Still, 324 American citizens have vanished since 2006 and not been found, according to the Mexican federal government’s official tally of the missing. That compares with more than 70,000 missing Mexicans.

The Aguilar case highlights some of the frustrations Americans face when forced to confront the weakness of the Mexican criminal justice system, one in which those accused of violent crimes are often acquitted, even when they confess. Law enforcement officials in the United States say it can be frustrating for family members when they realize U.S. police have no jurisdiction in Mexico and have to rely on their Mexican counterparts to investigate cases of missing Americans.

“People can be shocked to find out that the American law enforcement system doesn’t exist in Mexico,” said Lt. Thomas Seiver, who is with the homicide unit of the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department.

Asked to comment, an FBI spokesperson said in a statement, “While the FBI does not have jurisdiction on missing persons overseas, we are always ready to assist our international partners.”

Aguilar was last heard from on Aug. 20, when he sent his family a WhatsApp message from near his Rosarito beach house, where he lived some of the time.

Weeks went by, Izquierdo claims, before investigators began taking the case seriously, and that was only after the case gained traction in the U.S. press and Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti announced at a news conference that the city “would work tirelessly” to ensure Aguilar’s safe return.

“This is a living nightmare,” Izquierdo said. She said it was especially hard not knowing whether the father of her two children was alive or dead. “Since this happened, we’ve been meeting all these families in Mexico who have also been searching for their loved ones for years and have been left without answers.”

Though two people have been arrested for Aguilar’s “forced disappearance,” his whereabouts remain unknown. “I believe that every single hour after his disappearance was valuable,” Isquierdo said last week. “A lot of time was wasted with people who did almost nothing.”

Baja California investigators dispute that, saying they worked the case harder than most cases — not just because the missing party was an American, but also because there were immediate and obvious signs of foul play at Aguilar’s residence, such as missing vehicles, an apartment left in disarray and blood at the scene.

“They investigated day and night,” said Enrique Méndez, a spokesman for the attorney general’s office in Baja California.

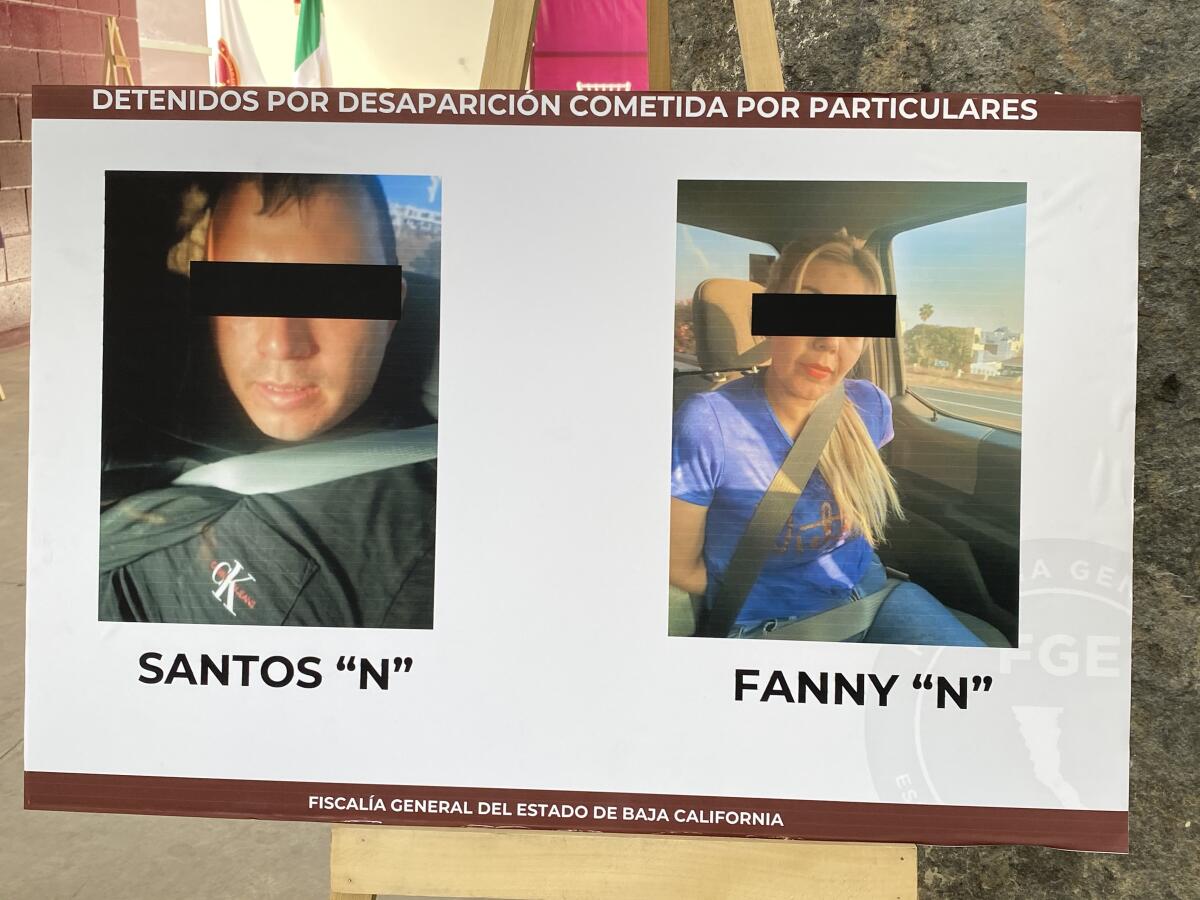

Two suspects were arrested Oct. 8, in possession of Aguilar’s credit cards. A judge briefly released them from custody a few days later. Baja California officials say the suspects — Santos “N,” 27, and Fanny “N,” 32 — are now back in custody, held on suspicion of being involved in Aguilar’s “forced disappearance.” (Defendants in Mexico are only identified by their first name unless they are convicted of a crime, in order to protect their civil rights.)

“It is incredible how having the evidence, having the audios, looking at photographs, looking at how these criminal groups do very severe damage to society, but just because of technicalities, because of details of interpretations and personal criteria, [the judges] let them go free,” said Isaías Bertín, a top federal law enforcement official in Baja California.

Oscar Armenta, a former San Diego police sergeant who worked extensively in Mexico on that department’s border liaison team, says in his experience Baja California investigators are talented, although they are often operating under very difficult circumstances, including limited resources and dangerous working conditions.

“I can personally tell you they’re outstanding at investigations,” said Armenta, who now works as a private investigator, often on cases with a cross-border emphasis. “They’re really good at boots on the ground, with the limited resources and the other challenges they face.”

U.S. law enforcement officials say Americans who don’t get involved in criminal activity in Mexico are rarely targeted because their disappearances can bring unwanted attention south of the border.

Criminal groups “don’t want the political backlash or the law enforcement backlash,” said Seiver. Armenta says it is “very rare that American tourists just walking down the street in Baja California will be just randomly kidnapped off the street.”

“Usually there’s some reason or a connection,” he said. “The suspects that are going to kidnap you want to make sure you have something for them to take.”

Still, there have been several high-profile robberies and slayings of American citizens in Baja California this year, such as the killings in August of a well-known Solana Beach couple who had a vacation home near San Quintin, a small coastal town about three hours south of the border near Ensenada. Ian Hirschsohn, 78, and Kathy Harvey, 73, surprised a robber in the house, investigators said. The robber later admitted to killing the couple and dumping their bodies in a well south of San Quintin, according to prosecutor Hiram Sanchez.

When U.S. citizens go missing in Mexico, relatives or other loved ones often start off looking for help north of the border.

San Diego-area law enforcement agencies are required by state law to immediately take a report about a person’s disappearance — no matter where the person lives or where they go missing. But police will then forward the report to the agency that has jurisdiction over the missing person’s case. If the person is believed to be in Mexico, they typically work through their border liaison unit to alert Mexican authorities.

“We don’t actively go looking for people in Mexico,” said Chula Vista Police Capt. Eric Thunberg.

Mexican local law enforcement agencies usually do not take a case based only on paperwork from another agency. Family members have to physically go to the jurisdiction where their loved one is missing to make a report in person in Mexico.

“We tell people all the time: If you think your loved one is in Mexico, go to Mexico,” explained Seiver. His unit, the homicide division of the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department, typically investigates missing-persons cases that are more than 30 days old.

Cases involving Americans missing in Mexico can draw extensive media attention, but their numbers are relatively low. The San Diego Police Department currently has 10 open missing-persons cases where detectives believe the person may be in Mexico. Since 2013, the Chula Vista Police Department has documented seven unsolved cases where the missing person is believed to be in Mexico.

The San Diego County Sheriff’s Department doesn’t publicly share its numbers of missing persons believed to be in Mexico for investigative reasons, but a homicide lieutenant said those numbers were also comparatively small.

In at least some of those cases, the missing party does not want to be found, police said.

“You’re talking about a grown person,” Armenta said, “so you know, the first question is always: Are they really missing or are they partying?”

But the alternative can be grim. In some years, more Americans are killed in Mexico than in all other foreign countries combined. Travel to several Mexican states is listed by the U.S. State Department as more dangerous than traveling to Syria or Afghanistan.

Though Baja California is considered less dangerous than many Mexican states, more than a dozen Americans are killed there each year. (This year, from January through June, there were nine deaths.) In 2019, 12 U.S. citizens were killed in Tijuana, data show.

The disappearance of Americans can bring much-needed law enforcement attention to specific criminal groups, which can help other Mexican families searching for their missing loved ones. When the remains of the missing Solana Beach couple were discovered in a well south of Ensenada, authorities also discovered other bodies in the same location.

“We have to wait until they find an American for them to look,” said Lupita, the mother of a missing Baja California woman, who asked that her last name not be used to protect her personal safety.

Lupita, who is still searching for her daughter, said the deaths of the American retirees were horrific and tragic. At the same time, she hoped some valuable information could come of it.

“At least now,” she said, “some other [Mexican] families might have some answers.”

Fry writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune. UT reporter Alexandra Mendoza contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.