- Share via

Noel Aguilar was riding his bicycle on a sidewalk when he stole a glance at a couple of Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies and quickly pedaled away.

Within minutes of what began as a routine encounter, the 23-year-old was dead with three rounds in his back.

When Christian Cobian was stopped by deputies because his bike didn’t have lights, he ran from them with his hand underneath his shirt. Deputies said they thought Cobian, 26, was going to shoot them and fired 13 rounds, killing him. No gun was found.

In August, Dijon Kizzee, 29, was shot 16 times and killed by deputies who tried to stop him for riding his bike on the wrong side of the street in South L.A., spurring weeks of protests.

Kizzee’s death and the others highlight how deadly violence can erupt from minor infractions and has sparked criticism of law enforcement’s failure to deescalate such incidents.

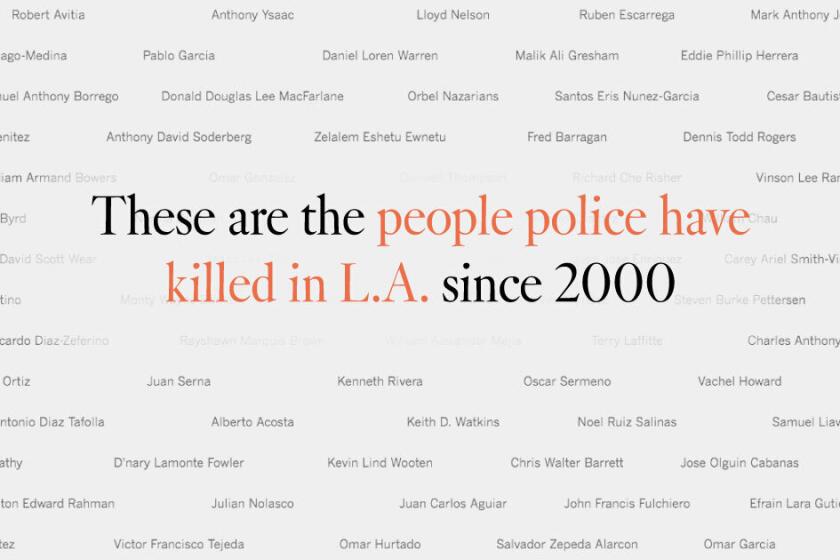

The Times identified 16 cases since 2005 where a stop for bike violations in Los Angeles County resulted in a police shooting, according to interviews and a review of public records from the district attorney, coroner and various court cases. Most of the stops occurred in communities made up largely of Black and Latino residents. In 11 incidents, including Kizzee’s, the bicyclists — all male and Black or Latino — were killed.

Among those 16 cases, violations ranged from riding on the sidewalk to biking without a light or on the wrong side of the road. In 11 cases, authorities said they found a firearm. In one shooting, deputies found an airsoft gun they said looked like a semiautomatic handgun.

Traffic stops have long been a source of controversy in policing, even more so now amid calls for police reform sparked by the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. The aggressive enforcement of minor infractions that law enforcement has long touted as effective under the “broken windows” theory of policing has been criticized for resulting in racial disparities and alienating residents without lowering crime.

A Times analysis in 2019 found that LAPD officers searched Black and Latino drivers far more often than white people during traffic stops, even though white people were more likely to be found with illegal items.

There has been much debate about who police pull over in a vehicle for traffic violations, but much less examination of how those laws are enforced for bicyclists. Bike stops are under particular scrutiny as cycling has become a safe alternative during the coronavirus outbreak for many people in poor communities who would normally rely on public transportation to get around.

An L.A. Times analysis found a black person was more than four times as likely to be searched by police as a white person, and a Latino was three times as likely.

It is difficult to find data on bike stops because many departments aren’t required to collect such information unless it results in a use of force.

In Tampa, one study found that Black cyclists were nearly three times more likely to be stopped than white cyclists, said Ojmarrh Mitchell, a criminology professor at Arizona State University who conducted the research.

New York Atty. Gen. Letitia James recently recommended that police cease conducting routine traffic stops because they too often escalate into violence. The guidance came as her office reviewed the death of Allan Feliz, who was shot and killed after he was stopped for allegedly not wearing a seat belt, as well as the New York City Police Department’s response to protests against Floyd’s death.

“Laws with a history of alleged disparate and discriminatory enforcement, such as bicycle operation on the sidewalk, ‘jaywalking,’ loitering, and fare evasion, should be repealed or removed from police enforcement,” her office said in a July report.

Seizing a gun or uncovering criminal activity during a stop for a minor traffic violation is considered good police work, and can boost an officer’s statistics and stature within a department.

But Jody Armour, a professor at USC who studies racial disparities in the legal system, said such interactions create a “reservoir of resentment.”

“It really robs people of their full participation in core community activities,” Armour said. “It starts to make second-class citizens out of people in stereotyped groups.”

Civil rights attorneys said countless more bicycle stops have resulted in the use of force by police or an arrest, sometimes only for resisting an officer, and criticized the use of petty violations as a way to profile people of color. Cycling advocates said such encounters have led them to rethink their push to get people on bikes in those communities.

“How often do we hear of those — white guy on a bike in Encino, shot dead,” said Humberto Guizar, an attorney who represented the family of Aguilar, who was killed in Long Beach in 2014. During that encounter, one of the deputies was accidentally shot by his partner. “That’s just a cop-out, a pretext to justify the misconduct … to justify the continuing mistreatment of communities of color in inner cities.”

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1996 that pretext stops are legal as long as someone breaks a traffic law. They are unlawful, the high court said, only when the officer’s true motives for a search hinges on a person’s race. Experts said that’s difficult to prove, though an argument could be bolstered with an analysis of an officer’s stops or a review of their social media activity.

“In reality, no one is going to say their motivations are racist,” said Ed Obayashi, a deputy sheriff in Plumas County and national use-of-force expert.

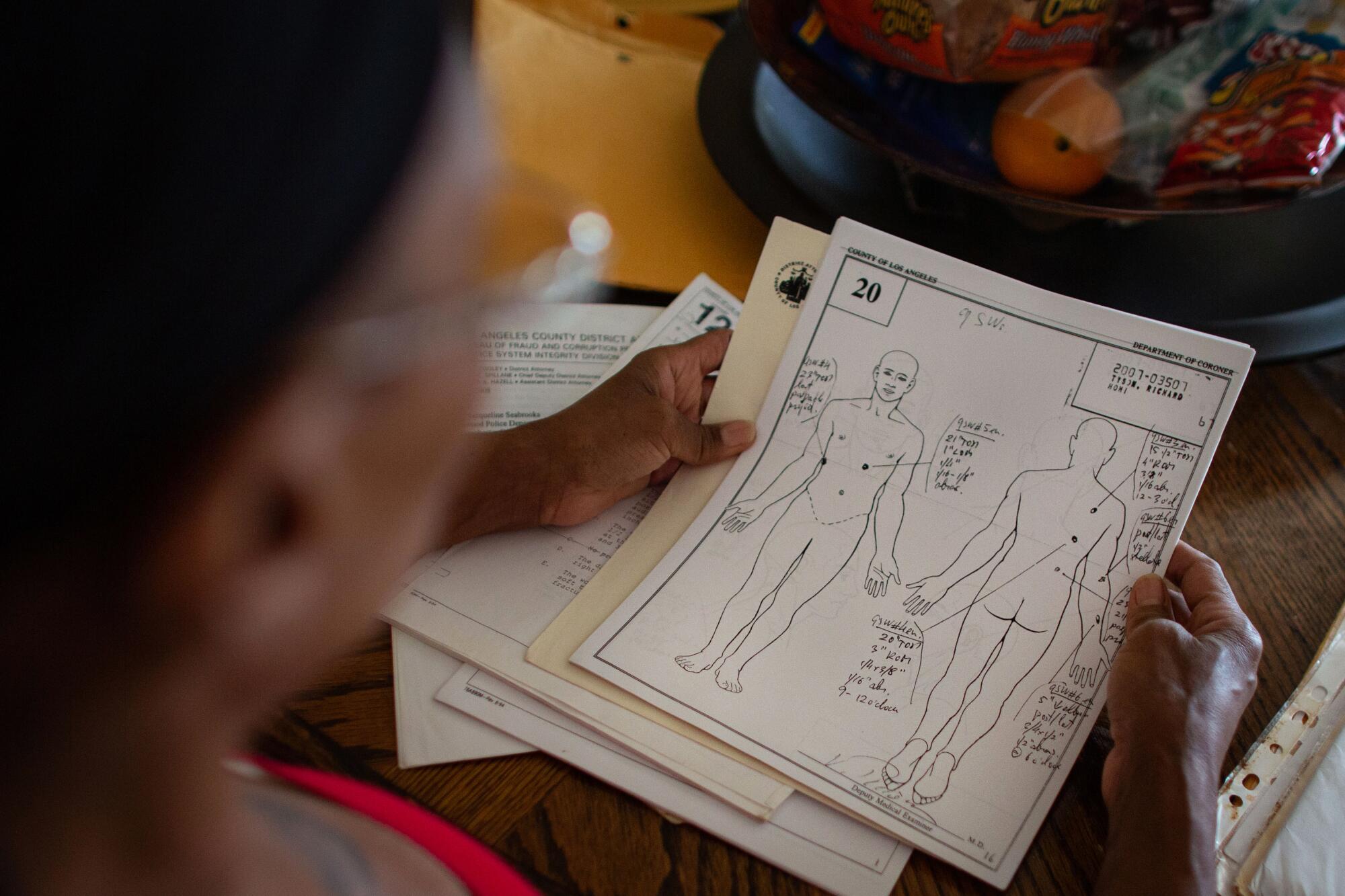

When two Inglewood police officers in an unmarked car said they recognized Richard Tyson as a gang member and tried to stop him for biking on a sidewalk, he kept riding, according to the district attorney’s review of the May 2007 case.

“Why are you always messing with me?” Tyson, 20, said, according to the review. “I’m just coming from the store.” The officers said he then adjusted a bulge in his waistband.

Tyson biked away, and the officers, who said they thought he had a gun, followed with lights and sirens. An officer chased Tyson to the backyard of an apartment complex, where he found Tyson crawling out of bushes. Tyson reached for his waistband and the officer fired six rounds, killing him. Paramedics found a packaged T-shirt in his sweatshirt pocket. There was no gun.

Prosecutors concluded that the deadly force was reasonable, saying “Tyson’s actions were consistent with a person who was armed and dangerous.” Tyson’s family sued the city of Inglewood and settled for $375,000.

Vershell Hall, Tyson’s mother, said she believes her son was “executed.”

“He was scared, that’s why he was hiding,” she said. “It’s almost as if he knew they were going to kill him.”

Like Tyson, Kizzee also ran after deputies tried to stop him for a bike violation. During a struggle with deputies, he dropped a jacket with a gun inside, the Sheriff’s Department said. Deputies later said they shot at Kizzee when he picked up the gun and pointed it at them. His family’s attorneys dispute that account and said witnesses reported that Kizzee did not have anything in his hands when he was shot.

Sheriff Alex Villanueva has portrayed the neighborhood where Kizzee was killed as crime-riddled and said budget cuts have eliminated youth programs and special enforcement teams. Through mid-September of this year, he said, there were a dozen homicides and 115 arrests of individuals with firearms — the “overwhelming majority” of whom are gang members — within a one-mile radius.

“We’re not out there terrorizing, we’re not there racially profiling, we’re not engaged in systemic racism of any kind,” Villanueva said at a recent news conference. “We’re trying to keep people alive. And it’s a very tough job.”

He sought to justify deputies’ stopping Kizzee, saying: “If something looks like it’s out of place or wrong, that’s what elevates peoples’ curiosity, deputies’ curiosity — they’re trained to be proactive in the right way. They don’t racial-profile, but they will criminally profile.”

Asst. Los Angeles Police Chief Robert Arcos said that his department is focused on building trust within communities that feel racially profiled and pushing officers to defuse tense situations. The department is also using body-worn video to help train officers on best practices during routine stops.

Arcos said officers respond to areas where crime is reported, but they’re also responsible for ensuring people are educated about traffic safety and enforcement. In some cases, a stop for a minor infraction “can escalate very quickly without knowing what was in that person’s mind at the time,” he said.

The Sheriff’s Department and LAPD both said that information on how often bike violations result in an arrest or use of force was not readily available.

Several more cases reviewed by The Times escalated into an arrest or allegations of officer misconduct, not a shooting. In one from October 2012, Alfonso Cerda, 44, was run over and killed by a patrol car that had pulled into a driveway to block his path as deputies attempted to detain him for biking without proper lights.

The district attorney’s office declined to file a vehicular manslaughter charge against the deputy who was driving, but the county settled a wrongful death lawsuit filed by Cerda’s three children and parents for $1.3 million.

“I’m still grieving,” his brother, Alvaro Cerda, said recently.

Kevin Shin, the senior director of public policy and partnerships for the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition, works with a variety of groups to educate cyclists on equipment and rules of the road, in part, to minimize the possibility of interacting with law enforcement. Shin said people are simply looking for a safe way to get around.

“It’s hard for them to do that when one of the greatest fears that they have is running into a law enforcement officer,” Shin said.

Lena Williams, 38, kept riding when police lights flashed on a trip to a doctor’s appointment in March. Williams teaches bike safety for the nonprofit People for Mobility Justice and knows the laws.

Williams was never given a ticket or told why the stop occurred.

“What am I doing wrong?” Williams thought. “Why, as a Black person, does my day have to be interrupted? Why do I have to be late for my doctor’s appointment?”

And after Kizzee was killed, Williams is reconsidering what it means to encourage people to ride bikes.

“It feels like, at this time, telling people to get on bikes is a death sentence,” Williams said.

Jose Beltran, who works in the nonprofit sector, said he was stopped on his bike at least nine times between 2009 and 2010. During one trip, from Cal State Los Angeles to his home in the Florence-Graham neighborhood, officers bombarded him with questions: Why are you out on your bike at this time? Did you do anything that might get you in trouble? When was the last time you did drugs?

Another time, Beltran said a utility pouch he wears while cycling was searched for weapons, then tossed back at him.

He decided to change his appearance, shearing his waist-length hair to a buzz cut, donning a reflective vest and wearing more athletic clothing, figuring officers would not think he was up to something.

But Beltran, 35, quit riding two years ago, in part because he still felt targeted by police.

“When I was a cyclist, I became kind of the go-to person to vent on,” he said.

It’s been 13 years since Tyson was killed in Inglewood, but his mother, Hall, 61, still keeps a file filled with documents related to his shooting. Each time she moves, the file comes with her.

In June, Hall, inspired by the activism surrounding the killing of Floyd, took to the streets to protest. Despite the arthritis in her feet that makes it difficult to walk, she said she “just had to” go out.

“I’m not done fighting for my son,” she said.

Staff writers Phi Do, Paul Duginski, Swetha Kannan, Iris Lee, Jennifer Lu, Maloy Moore, Ryan Menezes, Andrea Roberson and Aida Ylanan contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.