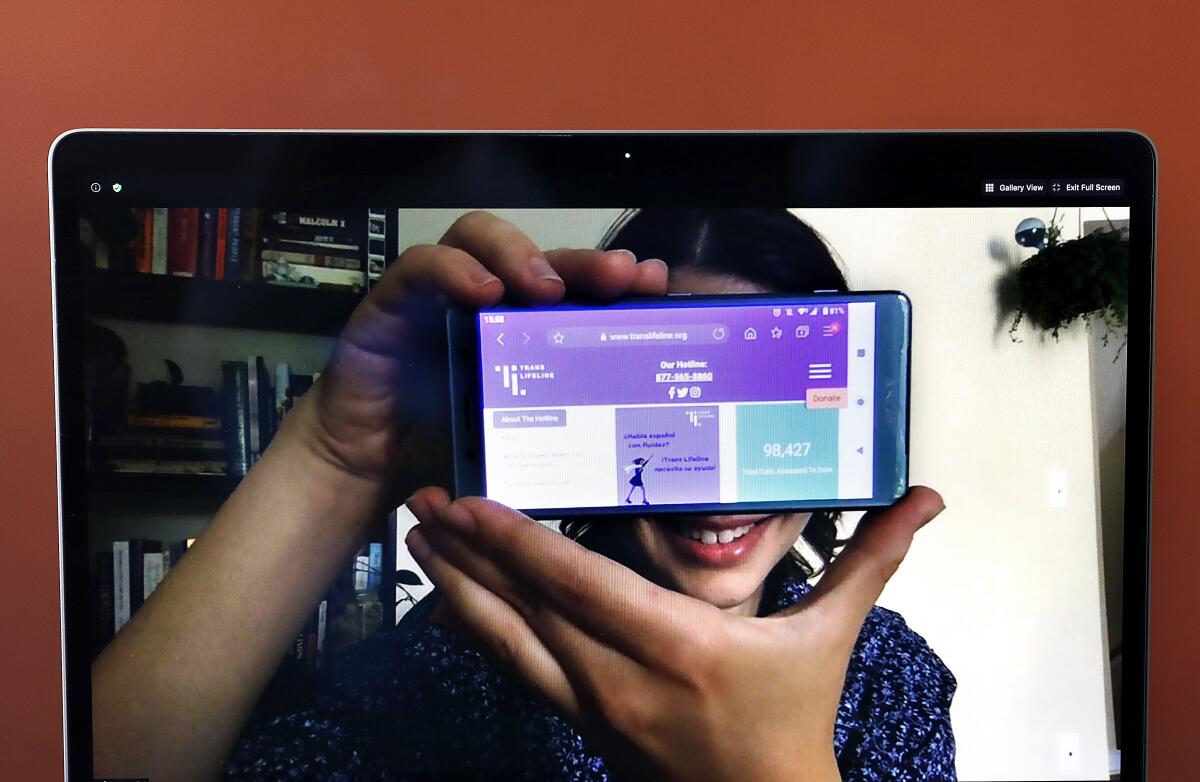

A crisis hotline for transgender people, by transgender people

Oriana went through the usual motions of preparing for a two-hour shift on the hotline. They filled a big glass of water, swaddled their armchair in a blanket and laid out a crochet hook and yarn on the desk, in case there was a lull in calls.

Downtime was unlikely, though, on this summer night.

The Trump administration had just finalized a rule that would reduce protections for transgender patients from discrimination by doctors, hospitals and health insurance companies. And Trans Lifeline, which describes itself as the only crisis hotline for trans people operated entirely by trans people, is flooded with calls every time the nation’s highest office does something that threatens the LGBTQ community.

The calls come from those seeking help, as well as prank callers urged by alt-right websites to scare and traumatize trans people in their most vulnerable moments and to tie up the lines so that those reeling from the news can’t get through.

Oriana, a nonbinary 28-year-old who uses the pronouns they, them and their and asked to be identified only by their first name for fear of being targeted, volunteered for this extra shift in mid-June to make sure that no calls went unanswered.

These interactions are bruising, even for an experienced operator like Oriana. But they only serve to validate why Oriana is doing this work in the first place.

It is an act of perseverance — and resistance — that is more important than ever in this era of heightened hostility. In six years, the hotline has answered more than 65,000 calls, with operators available 24/7.

The need to social distance during the COVID-19 pandemic creates new pressures, amplifying the sense of isolation and loneliness. Calls in which people describe suicidal thoughts to operators have increased 89% since March.

That June night when Oriana braced for extra calls, it was indeed a busy night and abusers hurled insults their way. But Oriana also got a call from a woman who had just come out. She wanted to celebrate with someone who could truly understand the immensity of the milestone.

“Honestly,” Oriana said, “that made it all worth it.”

::

Trans Lifeline was founded in 2014 by San Francisco software engineers Nina Chaubal and her partner, Greta Martela.

Chaubal had come out as trans a year earlier, and Martela, also a trans woman, had wrestled with depression and suicidal thoughts. In those dark times, Martela experienced ignorance and neglect from mental health professionals she reached out to for help.

Throughout their lifetimes, many trans people face rejection from family and friends, are victims of discrimination and harassment, and live in fear and isolation — factors that increase the risk of suicide. Four out of 10 transgender adults reported attempting to take their own lives at some point, according to the National Center for Transgender Equality.

Chaubal and Martela imagined a support network that would confront this epidemic head-on.

“When it started,” Oriana recalled, “it felt very much like an outgrowth of a natural community phenomenon: trans people connecting other trans people to other community members in a very grass-roots but enthusiastic fashion.”

Today, Trans Lifeline says it is still the only hotline in the country staffed entirely by transgender operators. The 70 volunteer operators undergo 36 hours of online training.

The organization has grown consistently, with the first big jump in donations and calls coming just after Donald Trump was elected president in 2016.

“People were terrified,” said Elena Rose Vera, executive director of Trans Lifeline.

Their fears were prescient. In 2018 alone, the Trump administration vowed to ban transgender people from military service and scrapped Obama-era guidance that encouraged school officials to let transgender students use bathrooms that matched their gender identities.

Then came an effort to establish a legal definition of gender under Title IX that failed to acknowledge the very existence of trans people. Trans Lifeline’s operators answered more than 20,000 calls that year.

There have been growing pains. In early 2018, Trans Lifeline’s board removed Chaubal and Martela after an internal review found that they had diverted “significant funds” to an unapproved side project.

Vera, a longtime educator, activist and reverend, was hired to help Trans Lifeline recover.

Vera focused on social justice and community care in her master’s degree studies at seminary school. But when she graduated in 2010, she discovered that most religious organizations — even those led by well-meaning progressives — were not ready to ordain a trans woman of color.

“They were comfortable seeing a woman like me as someone who required help,” Vera said, “not someone in leadership.”

She was eventually ordained in 2016 through the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples in San Francisco, founded by the civil rights leader Howard Thurman.

Vera noted that many of her staff are people, like her, who were denied professional opportunities elsewhere because they are transgender.

“When you give people the chance to do good work,” Vera said, “they bloom.”

::

They call looking for support groups or information about starting hormone replacement therapy.

They call in the wake of tragedy, such as mass shootings, or events that affect them directly, as when the Trump administration in 2019 banned transgender people from serving in the military.

They call from detention centers, from the Deep South and rural New England, from their childhood bedrooms.

Some call for no particular reason other than to talk to another transgender person.

A common, urgent fear among callers is that society will turn on them completely — a fear that has intensified during the pandemic and hit the trans community particularly hard.

As Oriana put it: “People who might have been doing OK are now struggling, and people who were struggling are now barely getting by.”

It can be difficult for trans people to secure employment and housing in the best of times. Three out of four trans people have been discriminated against in the workplace, according to a survey from the National Center for Transgender Equality, and 20% say they have faced prejudice while seeking a home. These hurdles are even higher for trans people of color, who are doubly marginalized.

Calls to Trans Lifeline about finding and keeping work, as well as workplace discrimination, have quadrupled since March, hotline data show.

“They’re really worried about finding new jobs,” Oriana said. “But it’s not just, ‘Will I be hired at all?’ It’s ‘How will they treat me when I’m there?’”

Oriana has talked to many young adults who have had no choice but to move back to the family homes they left in order to live authentically. With colleges shuttered, some were forced back into the closet.

Oriana helps callers brainstorm creative ways to express themselves in these circumstances and coaches them on how to find supportive communities online. In more dire cases, Oriana helps callers make safety plans, some of which involve escape.

But fleeing domestic abuse can be extremely difficult for trans people. Nearly a third of homeless transgender people report being turned away from a shelter because they are trans. In July, Vox revealed that a proposed Housing and Urban Development rule would allow federally funded homeless shelters to judge a person’s physical characteristics, such as height and facial hair, in determining whether they belong in a women’s or men’s shelter — a move advocates say could force trans women into men’s shelters.

Fearing discrimination, many have called the line worried that they might not receive adequate medical treatment if they catch COVID-19.

Vera recalled the reception she got from doctors after she was hit by a van in Oregon several years ago.

“They didn’t want to touch me or look at me. Their not wanting to help me as a trans person resulted in a lifelong disability,” said Vera, who uses a cane to help her walk.

Veronica Esposito, a 41-year-old operator in Oakland, says one of the most crucial parts of her job is validating the pain and confusion of her callers. “Yeah, I’ve been there. That really sucks,” she will say when a caller tells her about being stared at in public.

People will stare “like you’re not human,” Esposito said. “Like you’re a story that someone’s going to tell when they get home.”

Esposito understands the heartache of being rejected by family members. She intimately knows the dysphoria that comes when someone calls you by the wrong pronouns, or the name you used before you transitioned.

Oriana sometimes shares with callers that there were long stretches of times when they, too, felt hopeless; they thought about suicide, self-harmed.

But life is good now, Oriana tells them. Now they have a loving partner, a full-time job as a tech researcher. Their mental health struggles have been softened by therapy and time.

“I can’t promise you when you will be OK,” Oriana tells callers. “But I can promise you that that possibility exists.”

Added Vera, “We get to show that we aren’t just victims.”

::

Trans Lifeline is part of a long legacy of transgender people fighting for each other’s survival in a world that has by and large been hostile to their existence.

The first known transgender advocacy organization, Cercle Hermaphroditos, was founded in 1895 in New York City to “unite for the defense against the world’s bitter persecution,” according to Susan Stryker, a renowned chronicler of transgender history.

Those trans and gender-nonconforming urbanites, who convened quietly in an upstairs room of the gay bar and brothel Columbia Hall, paved the way for future generations of trans people to create intentional networks of support.

Pioneering transgender activists Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson founded Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, or STAR, in 1970 in an effort to help young trans people falling through the cracks of the burgeoning gay rights movement.

The movement matriarchs are Vera’s guiding stars. She aims to follow their model of sharing and mutual support and grow Trans Lifeline to a massive scale.

She says such an endeavor has never been so important.

At least 26 transgender or gender nonconforming people were violently killed in the U.S. in 2018, according to the Human Rights Campaign. That year, the white supremacist website the Daily Stormer reveled in state and federal efforts to curtail the rights of transgender people.

“We’re really doing it, guys,” a Stormer blog post reads. “We’re killing trannies — just with voting, and with mean words.”

And the FBI reported a 34% increase in hate-based attacks on transgender people between 2017 and 2018.

“Being able to provide anything that is steady and reliable at a time of historic uncertainty, to be able to say, ‘If you reach out, someone can pick up’ — that feels very vital to me,” Vera said.

For Oriana, whose friends love them not in spite of their gender identity but because of it, being an operator is a way to pay forward the support that so many trans people haven’t been afforded. There are trans folks in rural communities who had never spoken to another trans person until they called the hotline.

“The truth is, we’re out there. And there are a lot of us,” Oriana said. “I think it can be really hard to feel that reality when you’re isolated and the dominant culture is antagonistic toward you.”

So Oriana will keep taking calls from trans people in small-town Arkansas, in suburban Ohio, in upstate New York. They will counsel young and old on how to do makeup and how to hold on until their next therapy appointment.

On a recent Wednesday, as the sweltering Boston day gave way to nighttime breezes, Oriana stood up from their armchair and stretched their legs. They savored a piece of milk chocolate, a reward that marks the end of a shift.

Oriana took off their headset and put it aside for when they’d use it again next week. Same time, same place.

If you or someone you know is exhibiting warning signs of suicide, seek help from a professional by calling the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at (800) 273-TALK (8255).

You can reach Trans Lifeline at (877) 565-8860.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.