- Share via

SAN DIEGO — Twenty-eight years ago this month, John Kouris was a starry-eyed walk-on at the University of Notre Dame, a freshman wannabe tight end chasing a dream of football glory and answering to coaching legend Lou Holtz.

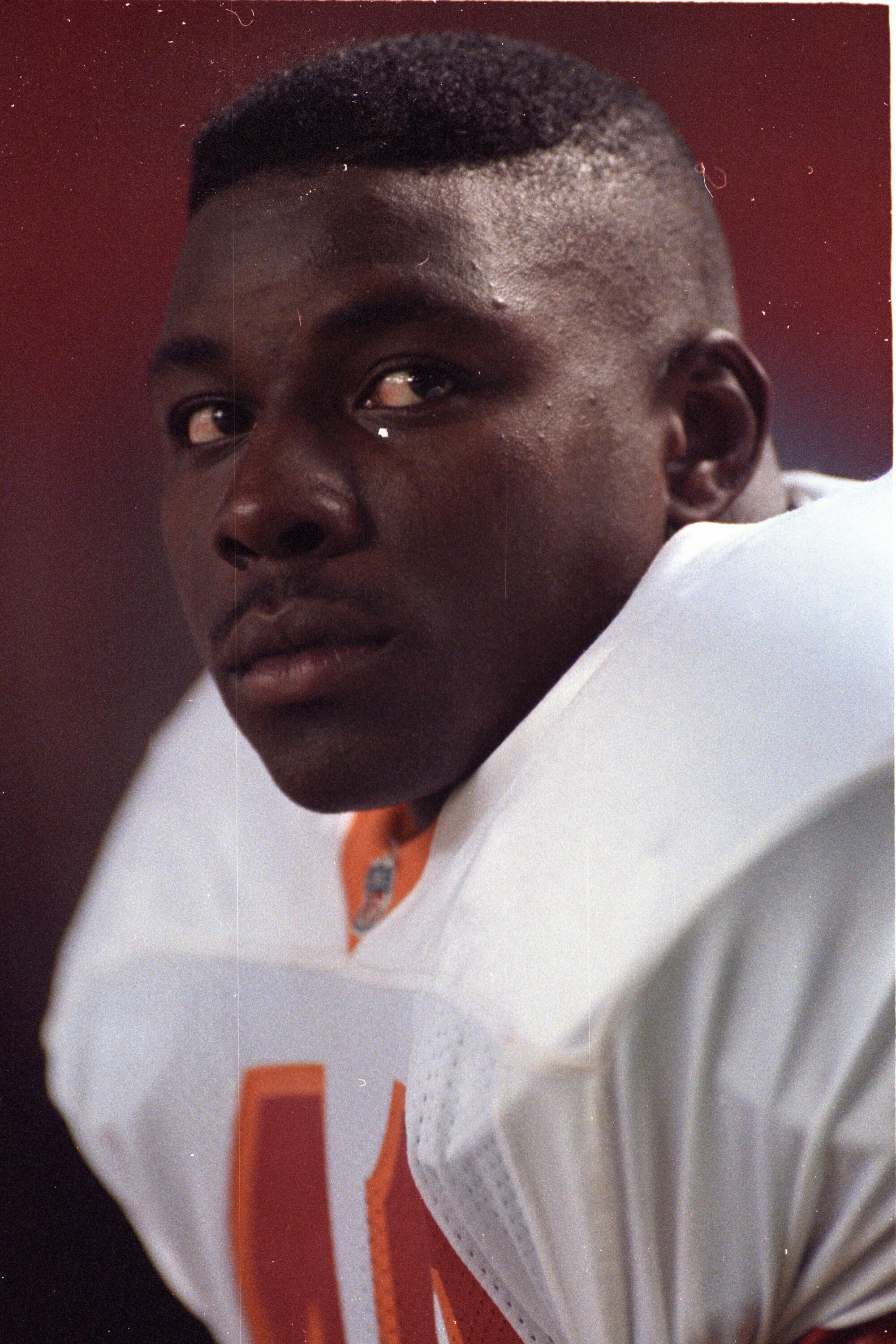

Kouris remembers the grueling two-a-day practices in 95-degree heat — especially the burly linebacker across the line of scrimmage, a returning All-American and defensive captain named Demetrius DuBose who kept knocking him off his feet.

“He annihilated me in practice,” Kouris said. “I remember seeing stars on many occasions.”

The senior linebacker — a shoo-in for the upcoming NFL draft who was known as “Demo” across campus — took the 18-year-old under his wing.

“He went really hard against me in practice, but as soon as we stepped off the field he was a guide, a mentor, somebody who gave me great insight into how to be a better football player,” Kouris said. “He found ways to buoy my spirits.”

One summer night in 1999, Kouris’ phone began buzzing with messages from former teammates: DuBose was dead, shot and killed by police in San Diego during some unexplained encounter.

“Everything turned black and I was cross-eyed,” he said. “I immediately started sobbing. It was horrible. Somebody that was so good to me.… I should have called him.”

In an instant, Kouris remembered the time DuBose pulled him aside and told him not to quit after not making the starting lineup for his first game. He flashed to the time DuBose showed up at his dorm room with a six-pack of beer, just to chat and listen to music.

And he thought of the last time he saw his former teammate, in 1994 outside the visiting locker room at Soldier Field, where DuBose and the Tampa Bay Buccaneers had lost their season opener to the Chicago Bears, and he thought of how he had let the relationship slip away.

“I yelled, ‘Yo! What’s up Demo?’” Kouris said of the 1994 encounter. “He had a huge smile on his face and we hugged it out and talked for like five minutes.”

Two decades later, Kouris is working to repay his teammate by telling his story in a documentary film tentatively titled “Things Behind the Son.”

The death last May of George Floyd at the hands of police in Minneapolis jump-started the Black Lives Matter movement and spawned worldwide calls for reform that continue today.

Questions about police use of force and conflict deescalation were front and center in the immediate aftermath of the DuBose shooting, but they faded away without the boost from the 21st century advances of cellphone video and social media.

Floyd’s death pushed Kouris, a successful Chicago-based food distributor to decide to invest the time and money it will take to finish the documentary film he first conceived years ago.

Kouris was in San Diego last week to interview DuBose’s friends and others familiar with what happened to his old mentor. His next stop was Seattle. Kouris said he has met with a major streaming company about distributing the film once it is completed.

The story of Demetrius DuBose deserves to be told, Kouris said, not only because he was another Black man who died at the hands of white police officers, but also because he was thoughtful and gracious and someone who genuinely cared about other people.

“There’s more to Demetrius than what you see when you Google him,” he said. “He is a complex, beautiful and multilayered human being. He was more than a football player. He was somebody’s son, he’s Seattle’s son, he’s Notre Dame’s son.”

Top-ranked prospect

Adolphus Demetrius DuBose was born in Seattle in 1971, blessed with what friends called a kind heart and seemingly limitless athletic talent.

By the time he graduated from O’Dea High School, just across the interstate from the home of the NFL’s Seahawks, DuBose was a two-time most valuable player and the top-ranked prospect in the state. He also excelled at track and basketball, and served in student government.

He chose Notre Dame over his hometown University of Washington Huskies, and earned a degree in government and international relations in 3½ years.

DuBose was selected by Tampa Bay in the second round of the NFL draft in 1993, and played there four seasons before being signed — and cut four months later — by the New Yorks Jets.

After football, DuBose traveled throughout Europe and dabbled in beach volleyball, which by 1999 had become a passion. He played in tournaments and invested in a professional tour run by Randy West.

That spring, West invited DuBose to move into the upstairs apartment he rented on Queenstown Court in San Diego’s Mission Beach.

The two had spent much of July 24, the day DuBose died, playing volleyball. They had plans to attend a barbecue that night, but when they got home West began tinkering with some new software that had been delivered that day and DuBose left to watch the sunset.

About 8:30 p.m., West heard a commotion next door.

DuBose, who toxicology records would show had traces of alcohol, cocaine and the drug Ecstasy in his system, had climbed over a railing to his neighbor’s balcony for a better view of the sunset. Then he saw a bed, entered the home, lay down and fell asleep.

Tenant Charles Flynn found DuBose when he arrived home, woke him up and told him he had to leave. The former linebacker complied and West, DuBose, Flynn and his roommate gathered outside to hash out what happened — but not before Flynn called police.

It’s not clear what Flynn told the dispatcher but officers said they were responding to a burglary that may still have been in progress. West said the four men had all but resolved the situation when the officers arrived at the scene.

“[DuBose] was embarrassed; he wanted me to vouch for him, and tell the neighbors who he was,” West said. “It was calm. The police showed up, but at that point they knew there’s no robbery going on.”

West said the officers started grilling DuBose about his arrest record — a disturbance charge at a South Bend, Ind., nightclub in 1998 and possession of alcohol when he was 20 back in college.

“We didn’t see the relevance, but he was cooperating, answering their questions,” he said.

But when the officers decided to handcuff DuBose, he resisted. They sprayed him with Mace and tried to tackle him, but DuBose flung them off his back one after the other and ran away, up the alley toward Mission Boulevard.

The officers tried using nunchakus to subdue DuBose but he was able to wrestle them away. Police opened fire, shooting DuBose 12 times, including five times in the back.

Community outrage

Questions over the shooting began almost as soon as DuBose was declared dead at Scripps Memorial Hospital in La Jolla.

The two officers — Timothy Keating and Robert Wills — told investigators they feared for their lives and that DuBose had assumed a “linebacker’s stance” before charging them threateningly. They said he appeared to be under the influence of PCP, a powerful hallucinogen.

Both officers were white. They said the fact DuBose was Black had no bearing on their actions.

Witnesses provided investigators conflicting information. Several said DuBose was advancing on the officers when they shot him; others disputed that. One even said she saw DuBose was up to 10 feet away and not facing the officers when he was killed.

Right away, the shooting provoked outrage in the Black community. Demonstrations were staged across the city for days. Police and city officials urged calm and pleaded with people to await the results of independent investigations.

In early November 1999, then-Dist. Atty. Paul Pfingst issued a report concluding the DuBose killing was justified.

“Virtually all witnesses who observed the shooting agree that Mr. DuBose took the officers’ weapons, and turned and faced the officers,” Pfingst wrote to the police chief. “Many stated he was swinging the nunchakus. Several saw him advance on the officers.”

By the end of that month, on the Friday after Thanksgiving, the FBI and U.S. attorney’s office in San Diego issued a report concluding there were no civil rights violations by officers involved in the DuBose case.

“It’s my opinion that a thorough investigation was done and there is nothing left to do,” said Special Agent in Charge Bill Gore, who later retired from the FBI and is now the elected San Diego County sheriff.

Five months later, after federal investigators found no civil rights violations, the city’s Citizens’ Review Board on Police Practices concluded in a report to the city manager and police chief that the shooting was tragic but also within existing department policy.

“Officers Keating and Wills perceived that they were left with no other force alternatives in the face of a threat to their safety and lives,” the April 2000 report said.

The citizens’ panel also assigned some measure of blame to police, however.

“While the officers conducted themselves within the bounds of existing policy regarding detainment, they did not exercise sufficient discretion within this policy,” the review board wrote.

The board also noted that DuBose was not resisting the officers until they sought to handcuff him — after telling him he was not in trouble — and that they had time to “evaluate the situation.”

‘An underlying fear’

West, now a program manager at the National Conflict Resolution Center in San Diego, followed each development in the DuBose case closely — the FBI probe, the district attorney’s justification finding and the review board’s determination and modest criticism.

He didn’t like any of it.

“The police were just intimidated by his presence,” said West, who was interviewed by Kouris outside the Mission Beach apartment last week. “The elephant in the room is he’s this big Black guy. He wasn’t threatening in any manner. I don’t know what the purpose of the handcuffs was.”

Jacqueline DuBose-Wright, Demetrius’ mother, sued the city of San Diego for wrongful death even before the district attorney’s office cleared the two officers.

Plaintiff’s attorney Brian Watkins, who tried the case over several weeks in early 2003, pointed to witness testimony conflicting with official reports and said race was an obvious factor in what happened to his client’s son. He said it was obvious the officers were afraid of DuBose because he was big and Black.

“That is an underlying fear that everyone can recognize,” Watkins said. “But we proved during that trial that Demetrius DuBose did not charge at those officers. He stood there in that spot and he died there at that spot.”

Jurors rejected the plaintiff’s argument, however, and found the officers acted reasonably.

Then-Deputy City Atty. Frank Devaney praised the verdict at the time, even as he acknowledged the tragedy that unfolded on Mission Boulevard that night.

Behind a provocative slogan is a growing movement that questions the role of police in American society.

Now a Superior Court judge, Devaney is more circumspect about expressing personal opinions on the behavior of police officers — or defendants. But he did say that changes in technology and the law over the years have sharply affected how the public responds to police shootings.

“If my case had happened last month instead of 21 years ago, I imagine it would have been a lot more publicized and made national front-page news,” Devaney said. “It was a different time. There were protests, but it wasn’t anything like it is nowadays.”

Bishop Cornelius Bowser of the Charity Apostolic Church in San Diego was not always a leader in the Black community. He used to run in a gang — and from police — and said he understands why DuBose did not want to be handcuffed.

“He was not high on PCP, but the police officer said he was,” Bowser said. “This is why they’ve been getting away with killing Black people over the years — the way they frame narratives. They used that as a foundation, as a code word to say this person was violent.”

Bowser recalled the fatal shooting in 1988 by San Diego police of an unarmed drug suspect named Johnny Douglas, which was ruled an “excusable homicide” by the district attorney even though Douglas had been shot in the back of the head.

He said the same mentality contributed to DuBose’s killing a decade-plus later.

“They shot him like 12 times; that is ridiculous,” Bowser said. “It shows you how they valued Black lives back then. I don’t think those officers had a worry in the world about being charged.”

Police accountability

Recent cases suggest police may be facing more accountability for using excessive and deadly force against unarmed people and low-level offenders.

The four officers involved in the Floyd killing in Minnesota are now facing murder and related charges. An Atlanta officer who shot and killed a drunk-driving suspect in June as he was running away also has been charged with murder.

And last month, San Diego County Dist. Atty. Summer Stephan filed a second-degree murder complaint against Aaron Russell, a San Diego sheriff’s deputy who shot

a suspect, Nicholas Peter Bils, outside the downtown jail after he escaped a state park ranger’s custody. It is the first time such a case has been filed by San Diego County prosecutors.

“When a life is taken, we must make decisions based in facts and law, and not ones that are influenced by the status of the accused as a peace officer nor the status of the victim,” Stephan said in the statement.

Watkins, the plaintiffs’ lawyer who sued San Diego police after the DuBose killing, said officers should not be permitted to shoot first and ask questions later.

“The law of qualified immunity says the cops can make an honest mistake and it’s OK,” he said. “There isn’t another profession that has that. Putting officer safety first means that everybody else’s safety comes second, and that needs to change.”

Kouris expects to finish his project by the end of the year. He said he hopes it will show viewers there was more to his friend than met the eye — and shine a light on police practices.

“Yesterday I was talking to 20 family members, and there’s a palpable emotional hole there still,” Kouris said by phone from outside Seattle. “It can never go away.”

From interviewing many of DuBose’s friends and relatives, Kouris said he learned the former NFL linebacker was depressed that his playing days were behind him. He was searching for the next chapter in his life and self-medicating to cope with the setback, as many people do.

“If I had done what Demetrius had done,” Kouris said, “I’m pretty sure I’d be here still, relatively unscathed.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.