Imperial County has highest rate of COVID-19 cases in the state; it wants to reopen anyway

Five days after Easter, the sound of helicopters hovering above Imperial County’s largest hospital was deafening.

There wasn’t enough room for a sudden influx of COVID-19 patients at El Centro Regional Medical Center. So new patients had to be transferred to hospitals hundreds of miles away. Helicopters circled overhead while waiting for the hospital’s only heliport to open up.

Judy Cruz, director of the emergency department, described the scene that day like something out of the 1979 war movie “Apocalypse Now.”

“Never had I seen helicopters flying out here like it’s Vietnam,” she said.

Below those helicopters, patients were screened inside military-grade medical tents set up in the hospital’s parking lot to handle the overflow. Inside the hospital, roughly 50% of all in-patients have COVID-19. The intensive care unit on the second floor has been unofficially renamed the COVID wing.

More than 200 COVID-19 patients have been transferred out of Imperial County, a rural community bordered by Arizona and Mexico that has the highest per capita rate of COVID-19 cases in California.

At first, they went to San Diego County or Palm Springs. But now patients are being transferred to Santa Barbara, San Francisco and Sacramento, county officials said.

The hospital saw similar surges after Mother’s Day and Memorial Day. Cruz is already scheduling extra staff for the next holiday.

“I know it’s just going to surge after Father’s Day,” she said.

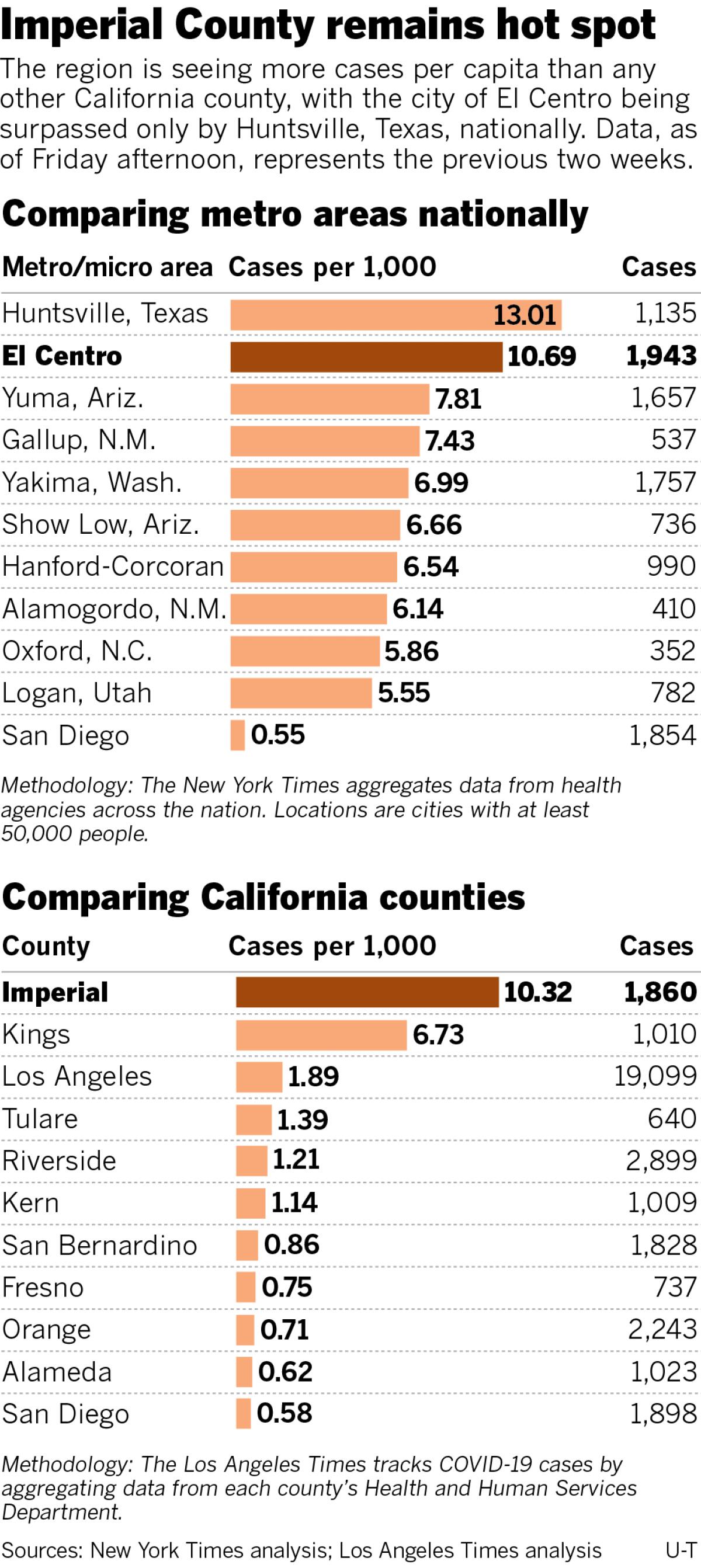

Over the last 14 days, the county’s rate was 1,078 per 100,000 people.

The county with the second-highest rate, Kings County, had 655 per 100,000. And Tulare County, which is third on the list, has a rate of 138 per 100,000, according to data compiled by the Los Angeles Times. In San Diego, the rate is 56 per 100,000.

A community divided

Despite those grim statistics – or possibly because of them – a recent push by local business associations and the county Board of Supervisors to reopen Imperial County’s economy has divided the community.

Imperial County meets all but one of the state’s benchmarks to ease pandemic restrictions. And it is a long way off from meeting that mark.

The state requires counties to have seven consecutive days in which 8% or fewer of all COVID-19 tests come back positive. Currently, roughly 24% of all tests in Imperial County are coming back positive, three times higher than the state benchmark.

Realizing the county won’t be able to meet this benchmark any time soon, the Board of Supervisors sent a letter to Gov. Gavin Newsom asking for local control.

Another letter, this one submitted by local business associations and cities, asks the governor to allow counties to make their own determinations regarding reopening instead of being beholden to the state’s one-size-fits-all approach.

Luis Plancarte, county chairman, said part of the reason behind wanting to reopen is that every region around Imperial County already has.

“If you look at neighboring areas, whether it is Mexico, Yuma, Riverside or San Diego counties, they’ve already to a certain degree opened up restaurants – with controls and social distancing,” he said Monday during a news conference. “We have seen a considerable amount of our community members who have gone out to those areas to either dine or recreate in other forms.”

Reopening locally, Plancarte said, could reduce the number of people leaving the county and would, therefore, lower exposure to the coronavirus.

Plancarte’s comments predated news out of Arizona that saw a surge in COVID-19 cases after the governor there lifted stay-at-home orders.

To be clear, the Board of Supervisors’ letter didn’t ask for Imperial County to reopen immediately.

Tony Rouhotas, the county’s chief executive officer, clarified that it only asked for local control and that any decision the county takes on reopening would be with the approval of the county health officer.

“We asked for local control; we didn’t ask for everything to be wide open,” he said.

Too soon to reopen

Hundreds of people throughout Imperial County believe reopening the economy too soon would put more people’s lives in danger.

More than 1,350 residents have signed a petition asking the governor to ignore the request of the officials elected to represent the community’s interests. The petition, started by the IV Nex-Gen Equity & Justice Coalition, also asks the state for more resources, including economic relief, to help Imperial County get through this crisis.

Instead of starting to reopen the county, the petition asks county officials to prioritize “advocating for community resources to get our infection rate down, and expanded economic relief and relief awareness for workers and businesses.”

“Reopening must happen only when it is safe to do so, or else we are accepting unnecessary deaths in our community,” the petition states.

Carmina Ramirez and James Taylor, two of the members behind the petition, live close enough to the hospital that they often hear the cacophony of ambulances and helicopters carrying COVID-19 patients.

Ramirez, who lost one relative to COVID-19, said the Board of Supervisors’ letter makes it seem like elected officials are prioritizing businesses over people – even if the reopening is done under the guidance of county health officials.

“It goes back to what’s more important, people or business,” she said.

Taylor, who has asthma and only leaves the house to buy groceries, put it more bluntly.

“If I’m an elected official, I would rather be responsible for a business closing than someone dying,” he said.

When Taylor began tracking the county’s COVID-19 case rate a couple of weeks ago, it was around 470 per 100,000. Even then, that rate alarmed him and he began to speak out about it on social media. On the day the Board of Supervisors sent the letter to Newsom, the rate had jumped to over 1,000.

“In the face of this elevated rate, I thought it was crazy for them to be doing that,” he said.

There are other things politicians can do to help local businesses, Taylor added.

Elected officials under pressure from business associations know that Imperial County has been among California’s poorest for decades. Even during booming markets, people struggle to make ends meet.

According to the latest census figures, 21% of Imperial County residents live in poverty. Per capita income for 2018 was $17,000 and household median income – that is for a family of four – was $45,000.

Economic losses mounting

In El Centro, where 40% of the city’s general fund revenues come from sales tax, Mayor Efrain Silva hears about business closures on a daily basis.

Silva attended two public funerals in El Centro this week. Monday was for a police officer and Tuesday was for an X-ray technician. Both died of COVID-19, and both died outside of Imperial County because they had been transferred to other hospitals.

“It’s been a difficult 48 hours for me personally,” Silva said Wednesday.

The mayor of El Centro supports the county Board of Supervisors. Forcing businesses to remain shut would cause greater harm in an already disadvantaged community, he says.

“I am of the opinion that we should try to open our economy as soon as possible because there is just absolutely no way that we can sustain the personal and economic losses in our community,” he said.

Any reopening, he said, should be done methodically and with the approval of county health officials, he added.

Silva has already heard from several businesses that simply won’t reopen. Because Imperial County is nowhere close to meeting the state’s benchmark for starting to reopen, he fears more businesses will follow.

“My fear is – getting back to that 8% – my fear is that we are not going to get there. Not any time soon,” he said. “Can businesses afford to remain closed another two or three or four months? I don’t think so.”

Cross-border tensions

The mayor recognizes this issue is dividing the community – in more ways than one.

One of the reasons attributed to the surge in COVID-19 cases is Imperial County’s proximity to Mexicali, a metropolis of more than 1 million people.

Mexicali has one of the highest cases of COVID-19 cases in Mexico. More than 3,100 people have been infected and 497 have died, according to data from the state of Baja California.

There are about 250,000 U.S. citizens and residents living in Baja California. And every day, thousands of them cross the border to work in Imperial County, Silva said.

This kind of cross-border travel has been a staple of border communities for centuries. But it is now viewed under a suspicious lens during the pandemic. Each side blames the other for spreading the coronavirus.

“Some people think that they may have picked it up over there and are bringing it here,” Silva said. “Mexicali people feel the opposite way, that we took it over there.”

Silva said some constituents have asked him to close the border, apparently unaware of the fact that the mayor of El Centro does not have the jurisdiction over federal immigration policy.

It is true that U.S. citizens who live in Mexico are being admitted to Imperial County hospitals at much higher rates than normal.

At El Centro Regional Medical Center, staff sees about 10 patients from Mexico every day, and nine of them are there because of COVID-19.

Underlying conditions

But Imperial County’s proximity to the border isn’t the only reason behind the surging COVID-19 rates. Academics and activists in the region point to a laundry list of circumstances that predate the pandemic.

“I can tell you there’s hypertension, there’s poor air pollution, there’s cancers, there’s asthma, there’s diabetes, there’s countless things people here are exposed to,” said David Olmedo, an environmental health activist with Comite Civico del Valle.

The organization set up 40 air pollution monitors throughout the county – including a couple south of the border – and found that pollution levels far exceed federal standards.

“They are exposed to the environment,” Olmedo went on. “Exposed to pesticide, exposed to contaminated water, exposed to the heat, there’s the fact that we don’t have the most complete medical services here so people travel to San Diego for specialized care or the fact that a lot of people would just rather go to Mexicali.”

Olmedo sees these factors play out in different ways throughout the day.

For example, every morning before dawn hundreds of farmworkers cross the border to work. They cross at 3 and 4 in the morning to avoid long border wait times but don’t begin work until a few hours later. So, while they wait to work, they wait outside in the streets with no access to public restrooms and no masks.

All of their lives, farmworkers have been told that pesticides and heat could kill them. But it hasn’t, so when they are told about the coronavirus, they don’t take it seriously.

“Of course they think COVID is going to be just another virus they can fight off; they’ve fought off everything else,” Olmedo said.

Because COVID-19 attacks the respiratory system, high levels of air pollution in Imperial County are particularly concerning.

“Exposure to air pollution impairs lung function, and it puts people behind the eight ball when facing the coronavirus,” said Vijay Limaye, an epidemiologist specializing in air pollution at the National Resources Defense Council.

A preliminary study from environmental health experts at Harvard University looked at the link between long-term exposure to certain air pollutants and coronavirus death rates. The study, which is being peer reviewed, adjusted for factors such as population density and smoking rates to try to isolate the effect of air pollution.

Researchers found that April’s data showed that even small increases in certain pollutants – specifically invisible fine particulate matter categorized as PM 2.5 – were associated with an 8% increase in death rates.

“In Imperial County, I think that finding takes on a whole new light,” Limaye said. “That county’s PM 2.5 pollution exceeds federal limits.”

All of these different factors contribute to the high number of cases in the county.

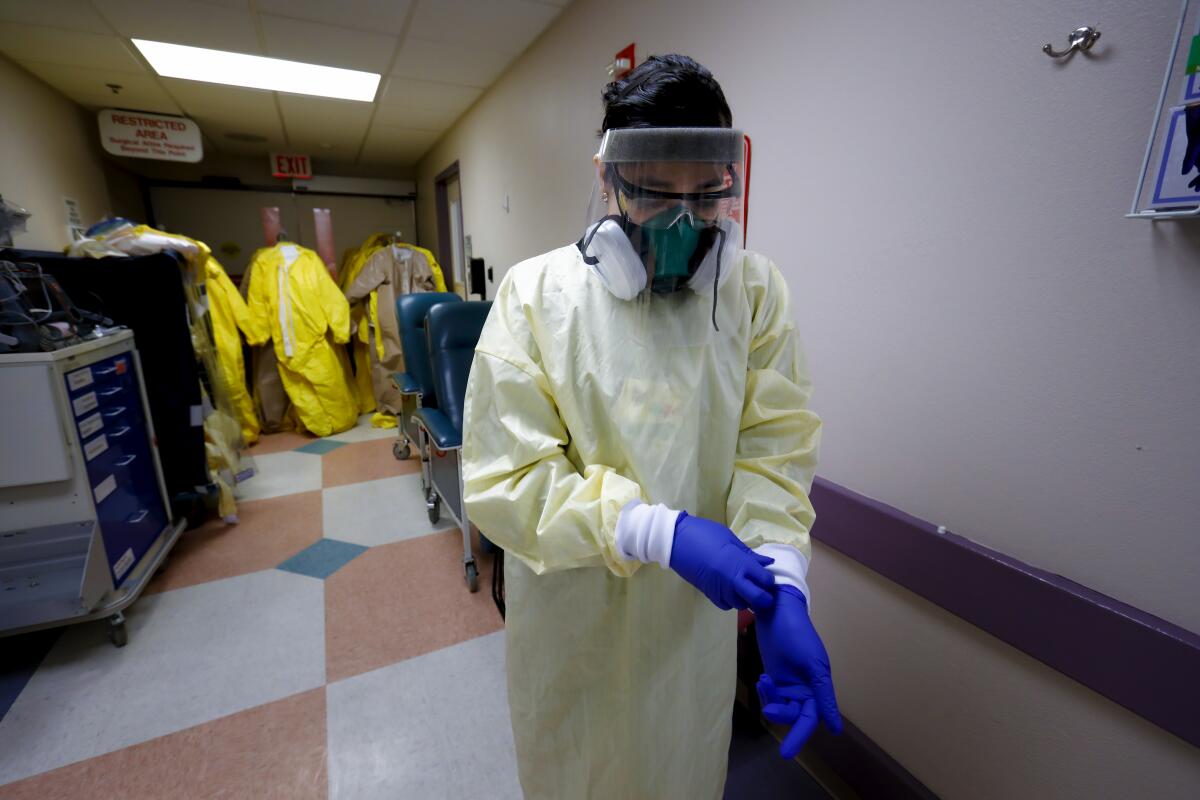

To help deal with the influx, staff is getting help from the National Guard and a federal team made up of nurses from all over the county. Those nurses are typically deployed to disaster zones, like Haiti after the earthquake. But now they are in El Centro during the pandemic.

The added staff is vital. They help take some of the pressure off from the day-to-day staffers, who have been working nonstop for about a month.

“They are exhausted,” said Cruz, the director of the emergency department. “Mentally, emotionally, physically exhausted.”

She hasn’t taken a day off either.

But she has found some time to sign the petition not to reopen.

“We’re not ready,” she said.

Solis writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.