Paroled from Angola prison, he searched for his son among L.A.’s homeless

- Share via

I stood at the front of the classroom in early October and made my pitch to the 25 students who had been accepted into Careers for a Cause, an inaugural training program in homeless services offered at Los Angeles Southwest College.

The homeless crisis in Los Angeles, I said, is rewriting the city’s history, and you are part of the story. May I join your class and talk to you individually about your backgrounds and what you’ll be learning in the weeks ahead?

I was interested in discovering what a curriculum in this job sector might look like. I had heard that agencies throughout the county were on a hiring spree for outreach workers, administrators, counselors. By one estimate, there were nearly 1,200 openings.

After taking a few questions, I stepped into the hallway so the students could make their decision in private. When they said yes, I began visiting the class each week as instructors discussed communication skills and resume writing and experts addressed the riddle of homelessness, mental health and trauma.

By then, a few students had approached me individually. There was Earl Williams, and there was Patrick Coston.

What Coston said to me was especially memorable: He had just finished serving 24 years in Louisiana’s Angola prison and was in Los Angeles searching for his son, Ian, lost on the streets, homeless and mentally ill. Coston impressed me as a man who wanted to make up for lost time and reconnect with his family.

Sadly, his dream was cut short.

He died on Dec. 1. He was 56. His death came from natural causes; he was an insulin-dependent diabetic. But his classmates were stunned. They had been drawn to his sincerity and kindness.

“His life is an inspiration to me and to many others,” said Francisco Villarruel. He and Coston had sat next to one another. Villarruel was younger. Almost 20 years separated them, but they had prison in common.

“His words pushed me to work harder,” Villarruel said. “Spending most of your life behind bars, life passes you by, and Patrick knew this.”

I visited Coston shortly before he died. He was living with his ex-wife, Robin Antoine, in Inglewood. Paroled from Angola on April 23, he had arrived in Los Angeles two days later, and Antoine put him up on a daybed in the dining room of her small apartment.

I wanted to learn more about his missing son, a common tragedy nowadays in Los Angeles made more poignant by the years the two had been separated.

Coston remembered well the day in the courtroom, in October 1996, when a judge sentenced him to 247-and-a-half years in prison for multiple offenses, including armed robbery and attempted armed robbery.

In the years before, he said, he had been doing seasonal work as a pipe fitter, then was laid off.

He and Robin were married at the time, with three children. They had no money. One day, he said, he robbed a patron of Harrah’s Casino in New Orleans at gunpoint. A second attempt — and second arrest — resulted in the life sentence.

“I was broken, and I needed help,” he told me. “My deviant behavior came from my childhood. I didn’t like what I saw in the mirror. I am thankful that I didn’t kill anyone. Those robberies? They were a cowardly act.”

‘His words pushed me to work harder. Spending most of your life behind bars, life passes you by, and Patrick knew this.’

— Classmate Francisco Villarruel

During his trial, Antoine moved to Los Angeles with the children — Ian was 3 at the time — but she didn’t divorce Coston until 2009, “because I didn’t want this to be a hopeless situation for him,” she said. “I still loved him.”

Besides, she said, he had been under a lot of pressure to support the family.

Surviving Angola took skills that Coston quickly learned. He mastered hierarchies in a prison population spread over 18,000 acres. Angola was known as the “last state plantation” by its inmates, most of whom were black.

However, in one instance, his instincts failed him. After “an aggravated fight” with another inmate, he said, and a further altercation with guards, he was placed in lock-down in a small cell, as he described it, for 10 years allowed outside for only one hour, three times a week.

In 2008, his mother died, and Coston began applying for parole, inspired partly by his daughter, Talia, who wanted to connect to her father and talk about her brother.

Not long after graduating from high school, Ian had begun showing signs of mental illness, made worse by drug use, Coston said. After spending a year at Patton State Hospital in San Bernardino for vagrancy and assault, he said, Ian was released into the care of his mother.

But a few days after Thanksgiving in 2017, with symptoms increasing he walked out of her apartment and did not return.

Antoine and Talia began to look for him. On Mother’s Day in 2018, they saw him in Torrance, his clothes torn, his shoes “flipping and flopping” on his feet. They tried to persuade him to come home, but he ignored them.

He was “all soiled,” Antoine said, “like he had been sleeping in the dirt.”

Coston redoubled his efforts to be released. Two hunger strikes led to negotiations and eventual reintegration with the general population — and the possibility of parole.

“I have now connected to God and to my family,” he said during his fourth parole hearing, “and I am in pursuit of my son.”

Careers for a Cause equips people to work in homeless services. These participants, fresh from their own hardships, can relate

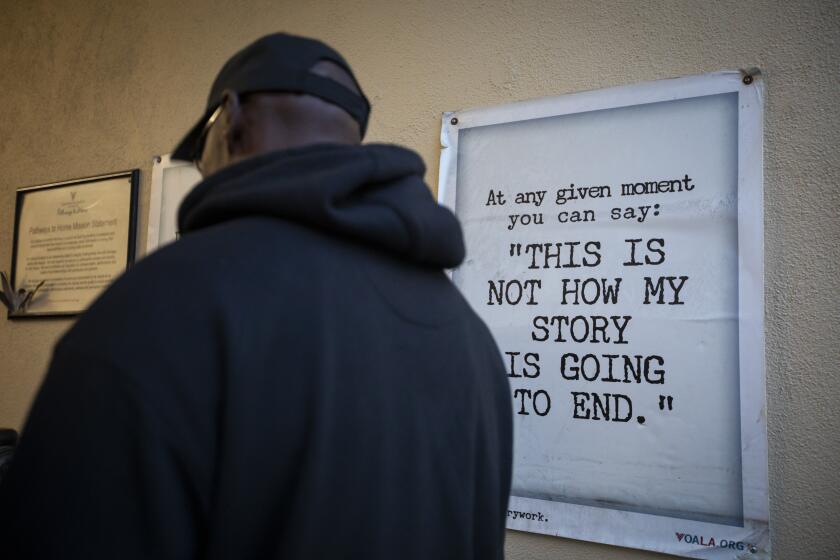

When he was finally released, he was shocked by what he saw on the streets of Los Angeles. The homeless crisis, he said, was “mind-boggling,” which was why he had applied to this program at Southwest College.

“I want to learn to be efficient and effective and bring resources to the unheard,” he said. “I want to help those who want to be helped. It’s my way of connecting to my son.”

He took buses to school, always on the lookout for Ian. Occasionally he and Antoine would get into her Prius and visit skid row. They spent hours at homeless encampments and showing residents a photo of Ian, his cap turned backwards, a wispy beard, thick eyebrows and his mother’s nose.

Antoine grew discouraged — “all the young men looked like Ian,” she said — but Coston said they had no choice: They had to keep searching.

The next time they went out, he told me, I could join them.

The week before his death, Coston put on a charcoal suit and alligator shoes — picked up at a clothing donation center downtown — and interviewed with the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority for a job. He was optimistic. When he was asked about his past, he told the truth.

“It was a negative experience with a positive outcome,” he said, citing his hopes for the future.

He died before I could help him search for Ian.

A GoFundMe page, titled Honoring Patrick, has been established by Antoine’s sister, Heidi Antoine, to help pay for his funeral.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.