Fires and sprawl threaten rare San Diego butterfly; now it’s proposed for protection

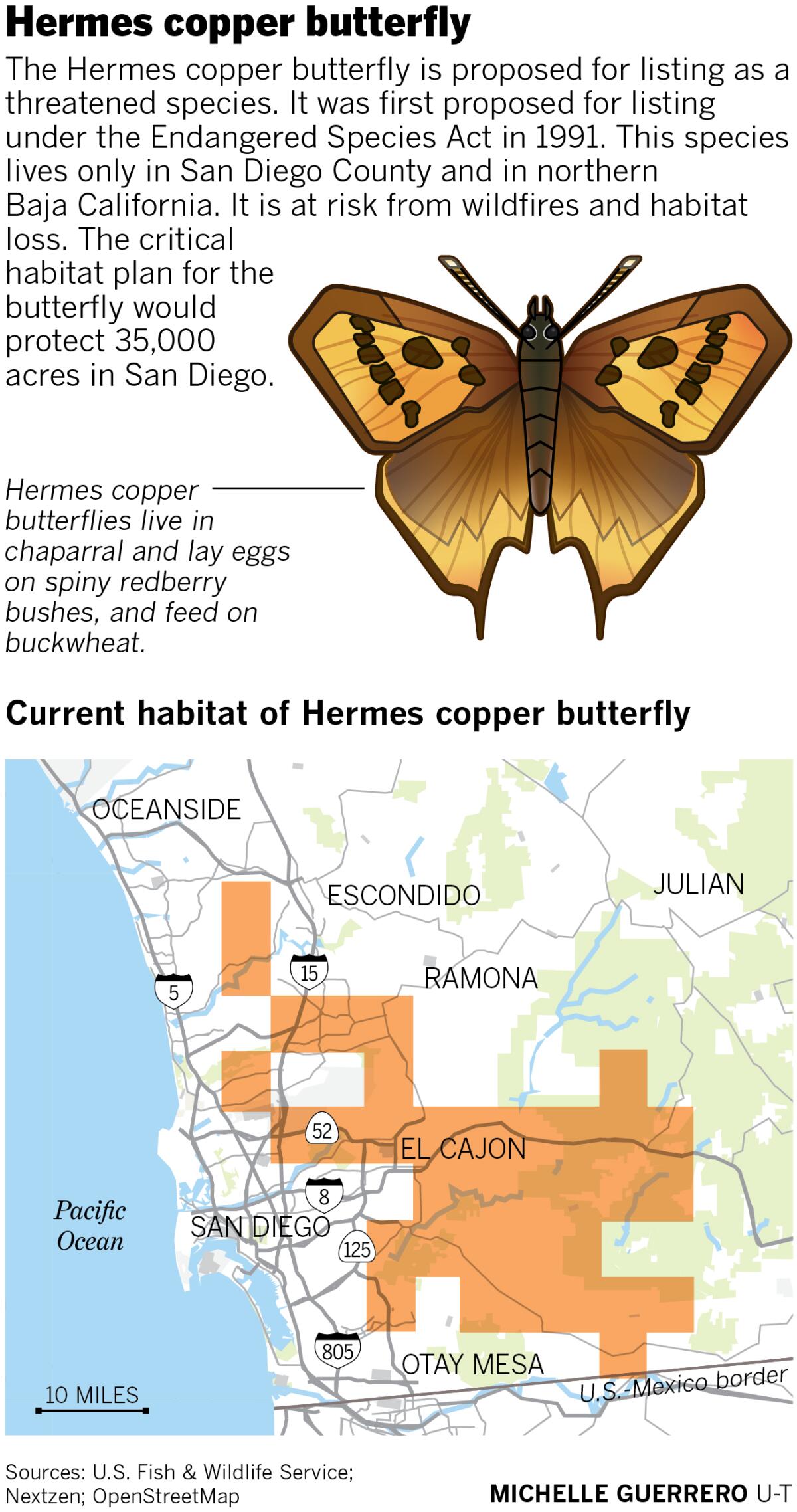

SAN DIEGO — The Hermes copper butterfly is particular about where it lays its eggs — spiny redberry bushes — and where it lives — only in coastal sage scrub and chaparral in San Diego County through northern Baja.

The tawny orange butterfly is one of a suite of local species that are specialized to the region and suffering from urban sprawl and savage fires that have altered the landscape in recent decades. Recognizing those risks to the species, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service this month proposed listing it as threatened.

“This is one of many pollinator species that are in decline across the country,” said Jane Hendron, spokeswoman for the Carlsbad Field Office of the Fish and Wildlife Service. “Unfortunately, there’s quite a number of our native butterflies in California that have suffered significant decline because of habitat loss, fragmentation and issues associated with wildfire.”

The Hermes copper is endemic to San Diego County and parts of Baja, meaning it lives here, and nowhere else. That makes it a valuable part of the region’s rich biodiversity, said David Hogan, president of the Chaparral Lands Conservancy, and one of the early petitioners to list the butterfly.

“This butterfly is one among dozens of endangered species in San Diego that are extremely specialized to our unique environment,” Hogan said. “San Diego County has an extraordinarily high concentration of endangered species.”

The service filed the listing proposal on Jan. 8 and estimates that it will take a year to finalize the listing and draw up critical habitat plans for the butterfly. The public comment period for the listing runs through March 9.

Despite plans for a swift turnaround, the listing has been a long time coming; the first petition to list the butterfly was nearly 30 years ago. In 1991, two conservation organizations, the San Diego Biodiversity Project and Center for Biological Diversity, petitioned to list the Hermes copper butterfly.

In the petition, they noted that interest in the butterfly dated back to at least the 1920s, when entomologist John A. Comstock, who developed the classification system for butterflies, wrote of the Hermes copper: “It is a fascinating little sprite as it darts about in the sunlight, or sports its showy colors while balanced on a tuft of wild buckwheat.”

Even then he warned that “it will always be a rarity and may, in fact, some day become extinct if San Diego continues to expand at its present rate.”

The butterfly, with brown and orange on the top of its wings and yellow dotted with black on the underside, is adapted to the fire-prone habitat of San Diego, said Tara Cornelisse, a senior scientist for the Center for Biological Diversity. The insect uses spiny redberry as a host plant to shelter its eggs and feed the larvae, and buckwheat as a nectar source for adult butterflies.

During earlier regimens of smaller, scattered fires, it would move between burned areas and blossoming sites.

“It can maintain that, but with urban development in San Diego and the presence of more wide-ranging fires, its habitat is more degraded,” with isolated patches of chaparral that are harder for the butterfly to access, Cornelisse said. “That’s what has caused it to become endangered.”

When the first petition under the Endangered Species Act failed to gain traction, the conservation groups followed with a second petition in 2004. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service analyzed and rejected it, concluding that it didn’t warrant listing, Hendron said.

The San Diego region had already survived the 2003 Cedar fire, and in 2007, it endured another series of firestorms that torched 368,316 acres, an area larger than the city of Los Angeles. That included swaths of old growth chaparral the butterfly relied on. Urban development spurred by a growing population claimed many more acres of that habitat.

By 2011, the Fish and Wildlife Service determined that it did indeed deserve protection. By that time, however, the service was complying with court-ordered deadlines for other environmental reviews, and ranked the butterfly listing as “precluded by other workload priorities,” said Listing and Recovery Division Chief Bradd Baskerville-Bridges.

It remained on hold until this year, when the service issued its listing proposal, starting the process to protect it under the federal Endangered Species Act. Safeguards will include designation of 35,000 acres of critical habitat in San Diego County.

There are 45 sites where it is known to exist, out of 95 historical occurrences, Baskerville-Bridges said. Many of those are in southeast San Diego County, he said.

About 65 percent of the critical habitat area is already within conservation areas or federal lands, Hendron said, while the remaining 35 percent is on private land. The critical habitat restrictions don’t apply to those, unless there’s a federal nexus such as federal funding or permits. Large development projects that require federal permits for land use or stream bed alterations could fall into that category.

“We’re continuing to work with project proponents in consultation,” Baskerville-Bridges said. “We don’t think it will be a hindrance, but we will continue to protect the species.”

San Diego County Building Industry Association Vice President Matthew Adams said the organization is still analyzing the proposed listing, but expects to comment on any provisions that affect home developments.

“We have to evaluate the maps and see where that is,” he said. “If it’s all in [multiple species conservation plan] land, that’s one thing. But if it could affect areas identified for housing, we’ll have to address that. Whatever the impacts, it’s another layer of bureaucracy we will have to address as we’re trying to provide housing for our citizenry.”

Hogan, for his part, is also concerned about the intersection of habitat and housing. He worries that master-planned communities proposed in the South County could sprawl over some of the butterfly’s remaining chaparral habitat, and said brush reduction measures laid out in fire prevention programs could claim more of it. Conservation groups will continue to press for the butterfly’s protection on multiple fronts, he said.

“Environmental groups will support this proposal and request that it be strengthened,” he said. “Whether it’s listed or not, environmentalists will ask that local agencies like the county and city of San Diego expand conservation measures under their respective multiple species conservation plans to provide protections for this species. And we’ll be asking the U.S. Forest Service and CalFire to revisit plans to destroy so much important habitat.”

Cornelisse said the Center for Biological Diversity will analyze the listing plan and critical habitat maps, paying close attention to exempt areas that should be included for the species’ protection, but said the measure is a step in the right direction for the Hermes copper butterfly.

“Generally, we’re very pleased with the fact that they’re responding to our petitions and our efforts,” she said, “and now it can get the help it deserves to hopefully survive.”

Deborah Sullivan Brennan writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.