One man’s 1,648-page quest to preserve an American watch company’s history

Fredric J. Friedberg of Irvine once owned more than 700 Illinois Watch Co. timepieces.

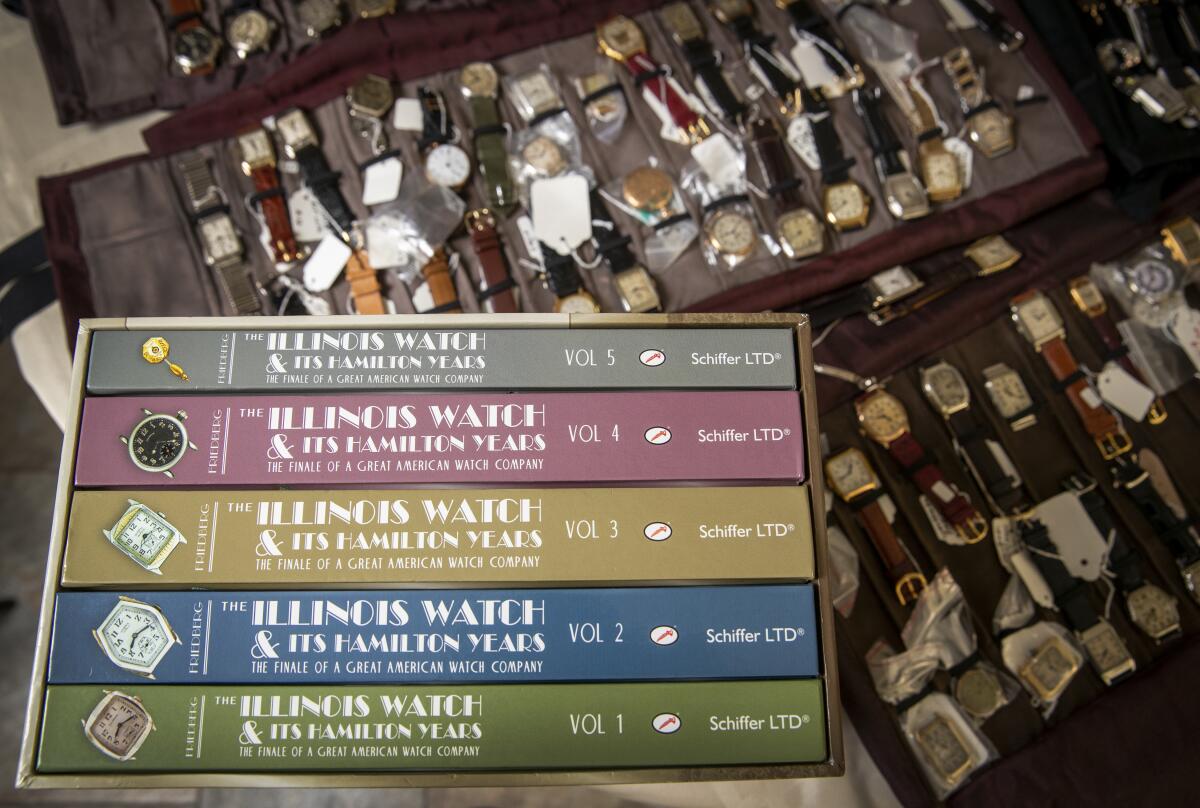

First, there’s the heft: 24.5 pounds.

Then, there’s the size: 1,648 pages.

But, really, it’s the topic of this five-volume book set that elicits the biggest surprise: the Illinois Watch Co.

Presidents, wars, social movements — few, if any, have prompted histories of this depth.

Yet Fredric J. Friedberg devoted a decade of his life to writing “The Illinois Watch & Its Hamilton Years,” a history of a defunct company that, odds are, you’ve never heard of before.

Though not a household name like Rolex, Illinois was once at the vanguard of a vibrant American watchmaking industry, crafting Art Deco-styled timepieces that rivaled the best from Switzerland in both accuracy and artistry.

Friedberg hopes his opus will reinvigorate interest in Illinois, which has been out of business for nearly 90 years. And even if it doesn’t, Friedberg could be satisfied knowing he completed a task that tested him in ways he never imagined when he began the work in 2008.

“My goal was to finish the book in two years,” said Friedberg, 75, a retired attorney who lives in Irvine. “I almost fried my brain on finishing the five-volume set.”

And among the indoctrinated — people like “A Clockwork Orange” star Malcolm McDowell — Friedberg’s project is peerless.

“There will never need to be another book on Illinois watches,” said McDowell, an Illinois collector. “He covered it.”

It’s a story of devotion. It’s a story of perseverance. And for Friedberg, who once owned more than 700 Illinois watches, it’s a story, by his own admission, of obsession.

::

Friedberg can’t explain why he became fixated on vintage watches. But even as a child, he was a collector of things. Marbles. Popsicle sticks. Pennies from 1943 that were made with steel due to a World War II-era copper shortage.

“I have no idea why I was doing it,” he said.

In 1988, Friedberg, then an attorney in his mid-40s, found a new thing to collect. He was in Washington, D.C., on business, and during a stroll down Wisconsin Avenue, a vintage watch shop caught his eye. “I didn’t know stores like this existed. I was shocked,” he said.

Friedberg went in without intending to make a purchase, but, of course, did just that, picking up a delicate, rectangular model made by Girard-Perregaux in the 1940s.

“It felt like I had found heaven,” he said.

He began buying wristwatches in earnest. Perhaps, he said, memories of his father’s watch — a Hamilton with diamonds on the dial — spurred him along. But he dismisses high-minded explanations for his interest in horology, the study of the measurement of time.

“I mean, I just had an affinity for it,” he said.

But McDowell has some ideas about the enduring allure of wristwatches.

“Look, none of us need watches, we have the iPhone,” said McDowell, who befriended Friedberg around 2012. “It’s about telling a story. A watch tells the rest of the world who you are. And Illinois watches really are as good as anything made in Europe. These are under the radar. You feel a little bit special that you know something about them.”

Unlike a mobile phone, or a battery-powered quartz watch, mechanical timepieces are powered by a movement composed of gears, wheels, levers and springs. It can seem almost like alchemy — that simply winding a watch can bring to life its innards, allowing for something as ephemeral as the passage of time to be memorialized.

Anachronistic? Perhaps. But it’s also romantic to some.

For Friedberg, though, it was more about the hunt, especially in the beginning. He just kept buying watches. But Friedberg also had a young family and a big mortgage.

“I was afraid I’d put my family in the poorhouse because every time I went by an antique store I’d go in and buy watches,” he said. “I’d come home and I’d have a pile of crap, and they weren’t working and ... and I said, ‘This is insane.’”

::

The Illinois Watch Co. was Friedberg’s salvation. Realizing he needed to narrow his focus, Friedberg homed in on the company’s wristwatches, their Art Deco elegance captivating him.

“No one touched Art Deco design like Illinois,” he said. “Plus it was an incredible story about American manufacturing, entrepreneurship and enterprise in this country.”

The Springfield, Ill., company was started in 1870, co-founded by industrialist John Whitfield Bunn, who had been a close friend of Abraham Lincoln. The company made its name turning out especially precise pocket watches that were used by railroads to keep accurate time, making train travel safer.

The factory that turned out Illinois’ precision instruments was a Gilded Age marvel. In a stroke of industrial innovation often overlooked amid praise for Henry Ford’s later accomplishments, the company’s timepieces were made on assembly lines.

John Cote, a member of the National Assn. of Watch & Clock Collectors’ board of directors, said the company’s standardized approach, especially when compared to the largely hand-made pieces coming out of Switzerland at the time, is an important example of American ingenuity.

“The American system of manufacturing things, it prevailed over the British and the Swiss, who were the watchmakers of the 1700s, 1800s and up to about the 1850s, when America started taking it over,” said Cote, an Illinois expert.

Illinois hit its stride during the boom years after World War I. Following the war, wristwatches became popular among men, in part because soldiers had grown accustomed to strapping pocket watches to their arms to more easily tell the time on the battlefield. According to Cote, during the 1920s, Illinois was the third-biggest American watch company by production volume, trailing only Elgin and Waltham.

It’s an inspiring era for modern American watchmakers including Cameron Weiss, who founded his eponymous Torrance-based watch brand in 2013.

“The inspiration for Weiss Watch Co. really lies with companies like Waltham, Elgin and Illinois,” Weiss said. “They were supplying all of America and many other countries with watches. Before that, watches were really only for the wealthiest of individuals who could afford a handmade item.”

But for Illinois, and later the rest of the American watchmaking industry, the boom years would soon end.

After its purchase by rival Hamilton in 1928, Illinois was buffeted by a series of changes and ultimately shut down during the Great Depression. Or, as Friedberg writes, the company’s “new corporate parent, faced with life-and-death choices, elected to allow only one watch operation to survive in the face of the most tumultuous economic conditions in the history of the United States.”

And by the end of the 1960s, Hamilton, Elgin and Waltham had all ceased operating as American companies, either shuttering or selling to the Swiss.

While Illinois’ story ended on a melancholy note, Friedberg reckoned it made for a great tale.

Before “The Illinois Watch & Its Hamilton Years,” there was an opening act. In 2004, Friedberg released “The Illinois Watch: The Life and Times of a Great American Watch Company.”

But he wasn’t satisfied with the book, which checks in at a comparably scant 272 pages. He began to fixate on the things he left out of the history, and friends noticed.

Television producer Greg Hart recalled visiting Friedberg’s home after the book’s release.

“I saw all of his material from the first book — he had boxes and boxes of things,” Hart said. “He said, ‘Look at all the stuff that never made it into my book. It’s been driving me crazy.’ I don’t think he could’ve died a happy man unless he told this story.”

So Friedberg started anew in 2008. By then, he was nearly two decades into his career as general counsel at Toshiba America Medical Systems. Eventually, Friedberg served as chairman of that company and two related ones headquartered in Chicago and in Edinburgh, Scotland. Regular travel to those locales — he visited Edinburgh at least once a month for eight years — afforded an opportunity to write. He always traveled with a hard copy of a chapter in progress.

“I never watched movies, but I would sip wine and work on the book,” he said. “I wasn’t good at sleeping on planes anyways.”

Friedberg worked his way through a trove of material: corporate minutes, patent applications, old advertisements and more.

But his meticulous approach could be a burden.

“There were times where he said, ‘How am I ever going to get this done?’” Hart said. “He took on a project that was never attempted in the history of the brand. I said, ‘Fred, how does a mouse eat an elephant? One bite at a time.’”

“The Illinois Watch & Its Hamilton Years” was released by Schiffer Publishing in May 2018. The $295 five-volume set is both sumptuous and encyclopedic, its in-depth history of the brand supplemented by a guide featuring every wristwatch model made by the company and essays from collectors, among other features. Volume Five even includes a 750-question quiz, and Friedberg writes that readers can email him if they “get stuck on any question.”

Schiffer Publishing printed about 1,000 copies, and about 500 have been sold so far. Among the buyers have been a handful of notable institutions and organizations: The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, the Abraham Lincoln Research Library and the National Assn. of Watch and Clock Collectors.

That’s a point of pride for Friedberg, and the book set also has won praise from a notable group: people in the family tree of Bunn, the company’s co-founder.

“We admire him tremendously,” said Andrew Taylor Call, a Bunn great-great-great grandnephew. “I would say in absolute faith that Fredric Friedberg knows more about the Illinois Watch Co. than anyone alive today.”

::

The decades were laid out in front of Friedberg on the kitchen table of his Irvine home.

More than 200 wristwatches in all, they told the story of 30-plus years spent buying, selling, cataloging, researching, writing and publishing.

Friedberg delighted in canvassing the array, which he keeps at a bank and brought home for a recent interview. He bobbed around the table as his wife, Joy, cooked vegan hamburgers she insisted Times journalists try (verdict: surprisingly meaty).

While Friedberg fussed over the watches, Joy said she has long known that he would “dedicate himself to whatever he gets into.” But five volumes?

“I don’t think I could’ve seen that far,” she said.

Still, she was reluctant to call her husband’s work an obsession.

“Maybe to him it’s an obsession,” she said. “To me, it’s like — there are people who have hobbies and people who have avocations. This is an avocation.”

The table glittered and flared as sunlight strafed it through the kitchen windows. Every so often, Friedberg would snatch up a rare piece to explain its provenance.

One of them was a 1928 Illinois Consul given by inmates of Michigan’s Marquette Branch Prison to the prison doctor on the occasion of his retirement. The solid white gold watch, which has been dubbed the “Convict Consul,” may have been a gift from imprisoned members of the Purple Gang, an infamous group that terrorized Detroit, Friedberg said.

Among the assemblage was the one that started it all: the Girard-Perregaux he bought in 1988. A paper label affixed to it read “#1.”

Friedberg has numbered all the watches that have passed through his hands. No. 3,729, No. 3,810 and No. 4,779 gleamed alongside dozens of others. There were gaps in the numbers, owing to those he has relinquished, some as part of an ongoing unburdening.

Friedberg began winnowing his collection a few years ago. After his sons made clear they were not interested in his watches, he moved to sell off the bulk of them. His new book set has made it easier.

“If I want to see them I can go open the book,” he said. “I don’t have to possess them. I can’t be selfish. I want it to go into the hands of someone who will appreciate it.”

But McDowell doubted Friedberg will ever really stop collecting.

“No, I don’t believe it — he’s just giving you a bit of Shinola there,” said McDowell, laughing. “Of course, he’s satisfied at having completed a task that took five times longer than he thought it would. But I happen to know there is a watch that he’s trying to get.”

When pressed, Friedberg conceded he isn’t quite done. When asked about his next purchase, he wouldn’t say much, but he knows one thing: it’ll be No. 4,989.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.