Black people still few and far between in San Diego’s biotech industry

- Share via

SAN DIEGO — San Diego biotechs are working to erase cancer, light up nerves during surgery and scan thousands of molecules with artificial intelligence.

The industry’s workforce, however, is less futuristic than its goals.

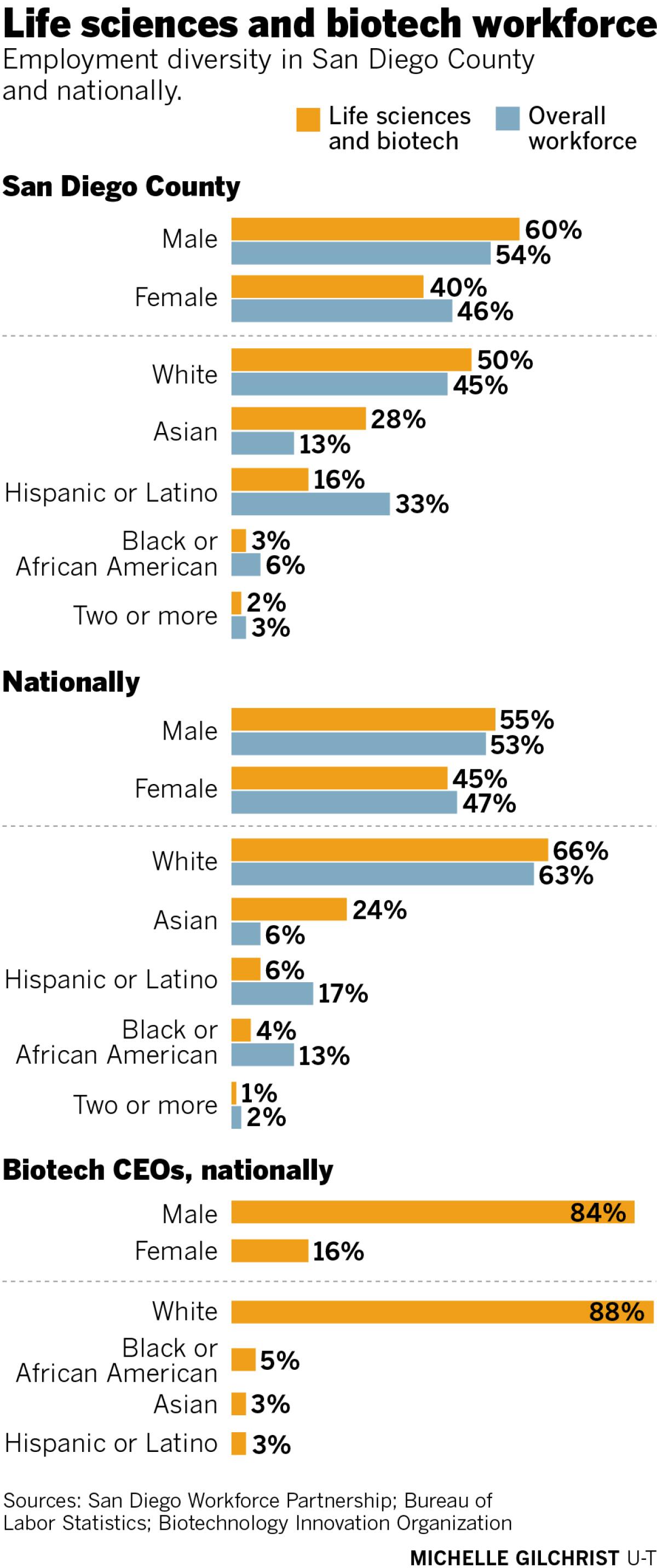

Black people account for 6% of the county’s overall workforce but just 3% of biotech, according to the San Diego Workforce Partnership. People identified as Hispanic or Latino, who represent a third of the county’s workforce, make up 16% of biotech.

To understand the dearth of diversity, we reached out to past and present biotech employees, recruiters, and the county’s research institutes, universities and colleges.

People highlighted several issues, including limited diversity in academic pipelines that feed into biotech, companies recruiting within their own network bubbles, and explicit and implicit bias in reviewing applications.

And getting hired is just the beginning. Black people within the industry said they had to work even harder to get noticed and rewarded for taking on challenging projects that would allow them to climb the corporate ladder. That may explain why minorities are especially scarce at the highest rungs of biotech.

None of these issues are new; biotech’s lack of diversity has been documented for more than 20 years. But the topic has taken on new urgency lately.

“I think this is a good opportunity now, with George Floyd, where we can all go back and really reflect and find ways out of systemic racism,” said Paul Mola, one of San Diego’s few Black biotech chief executives. “And, by God, what many don’t understand is that we all get better. The society gets stronger. The country gets stronger.”

Early challenges

The average San Diego biotech CEO is 56 years old, according to a 2015 report by Liftstream, a U.K. life science executive search firm. But the barriers that keep Black people out of biotech start far earlier in life.

A San Diego Union-Tribune investigation showed that Black and Latino public school students seldom have teachers who look like them. That holds true throughout higher education, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

“I’m happy to mentor students from underprivileged backgrounds,” said Guy Salvesen, dean of the graduate program at the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Institute in La Jolla. “But I’m an old white guy.

“I might say the right things, and I try to act on the right things, but I’m not the right kind of mentor. I don’t have the same background.”

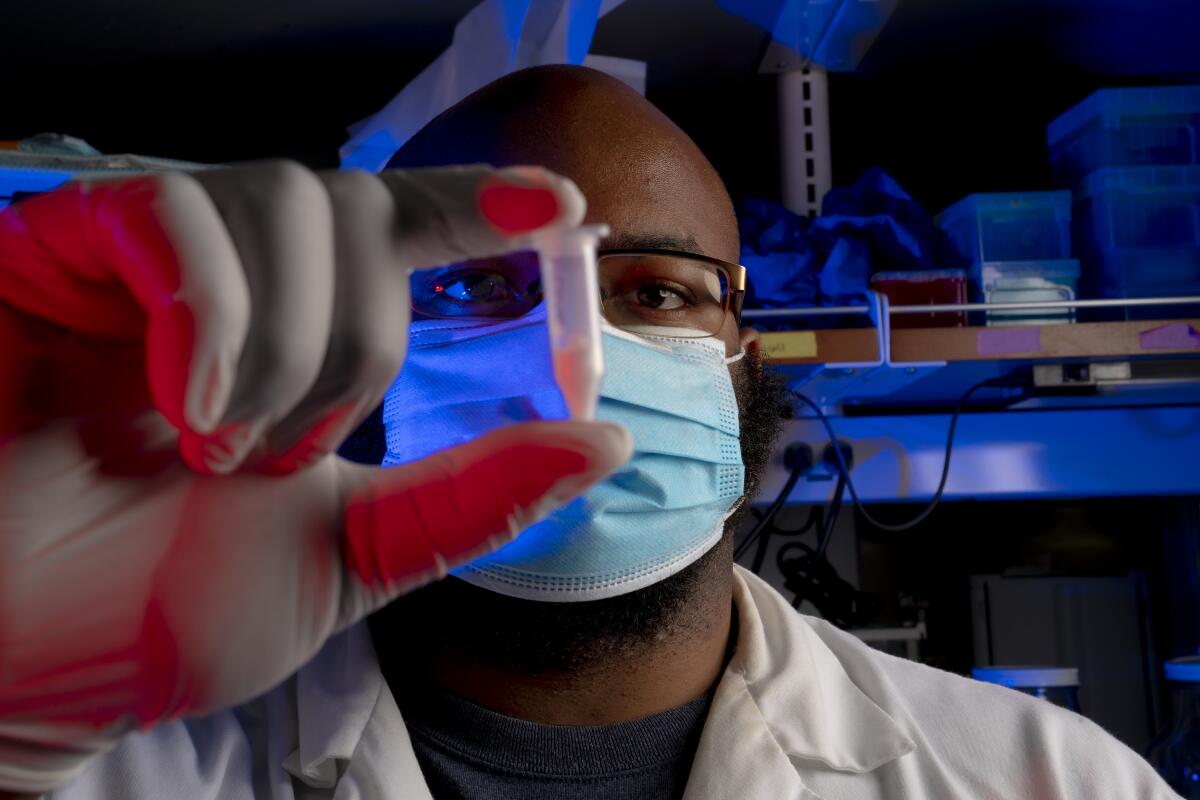

Having mentors and role models who look like you matters, says Jervaughn Hunter, a Black bioengineering graduate student at UC San Diego who is working on new, minimally invasive ways to treat heart disease.

It’s a project that’s hard to explain to family back in his hometown of Port Gibson, Miss., home to fewer than 2,000 people. Growing up, Hunter didn’t know anyone in biotech — or that such careers existed.

A survey of 67 workers highlighted the issues faced by people of color, women and LGBTQ people in the tech industry.

“There’s no one there to actually exemplify what that career is, so no one thinks to go into it,” Hunter said.

That creates a sort of self-fulfilling cycle, he says. You don’t see yourself represented in a career, so you don’t pursue it. And because you don’t pursue it, you’re not represented.

In Hunter’s case, a brochure from the University of Alabama at Birmingham that mentioned a biomedical engineering program piqued his interest. While at the university, Hunter noticed that some of his peers were joining labs as volunteers.

“I had no idea what that even entails,” Hunter said. “And then you find out that a lot of it is volunteer. If you’re not having college paid for and you have to work a job, you can’t really go and do these volunteer positions.”A numbers game — or maybe not

Hunter was able to land a position as a paid lab assistant, where he gained valuable research experience before applying to UC San Diego for graduate school. But the issues of access, representation and cost that he points to partly explain why there are so few Black students in the programs that train the next crop of biotech workers.

The Union-Tribune reached out to a number of local institutes. The participation of Black students ranged from a 10-year average of 1.5% for UC San Diego’s biotech-related doctoral programs to 4.5% for MiraCosta College’s bachelor’s in biomanufacturing. Percentages for programs at San Diego State, Sanford Burnham Prebys and Scripps Research Institute hovered in the range of 3% to 4%.

Experts call this the pipeline problem — the idea that there simply aren’t enough qualified members of underrepresented groups to hire.

But Ron Lewis, a chemist at MEI Pharma and one of the company’s few Black employees, doesn’t buy that argument.

Tech companies are famous for moving fast. Yet despite calling diversity a priority since 2014, they remain mostly white and mostly male.

“We know what universities are producing these scientists, what scientific meetings these students are going to,” Lewis said. “It’s a matter of asking internally, ‘Are we going to the right places?’”

Lewis has spent over a decade helping organize an annual meeting held for Black chemists and chemical engineers. Participants get to share their research and interview with representatives from pharma giants such as Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Merck.

Many companies fill open positions without casting such a wide net. San Diego biotechs tend to be small — odds are you’ve never heard of most of them. The companies aren’t subject to much public scrutiny about their hiring practices.

Without a fresh infusion of diverse candidates locally or elsewhere, expecting more diversity is a bit like shuffling a deck of cards and hoping to get more hearts.

Even when Black candidates apply, their applications often get weeded out because they don’t fit the mold hiring managers expect, said Ava Mason, who was often one of the only Black women at the biotech and pharma companies where she worked for 20 years. She now runs a nonprofit that exposes underrepresented children to science, technology, engineering and math.

“The constructs of hiring are set up to eliminate us at all kinds of different levels,” Mason said. “If the candidate didn’t go to a top-100 school, we can’t hire them. If the candidate didn’t graduate in consecutive years, we can’t hire them. Well, who do you think you’re eliminating? A lot of us.”

Other times, biases aren’t so subtle. Lewis remembers applying for jobs early into his career without any luck. A human resources manager offered to look over his resume and, noticing sections that identified Lewis as a person of color, suggested he remove them. That’s when Lewis’s fortunes started to change.

“It’s amazing how the script kind of flipped,” Lewis said. “The phone started ringing. You’re getting emails back saying they want to follow up.”

Difficult conversations

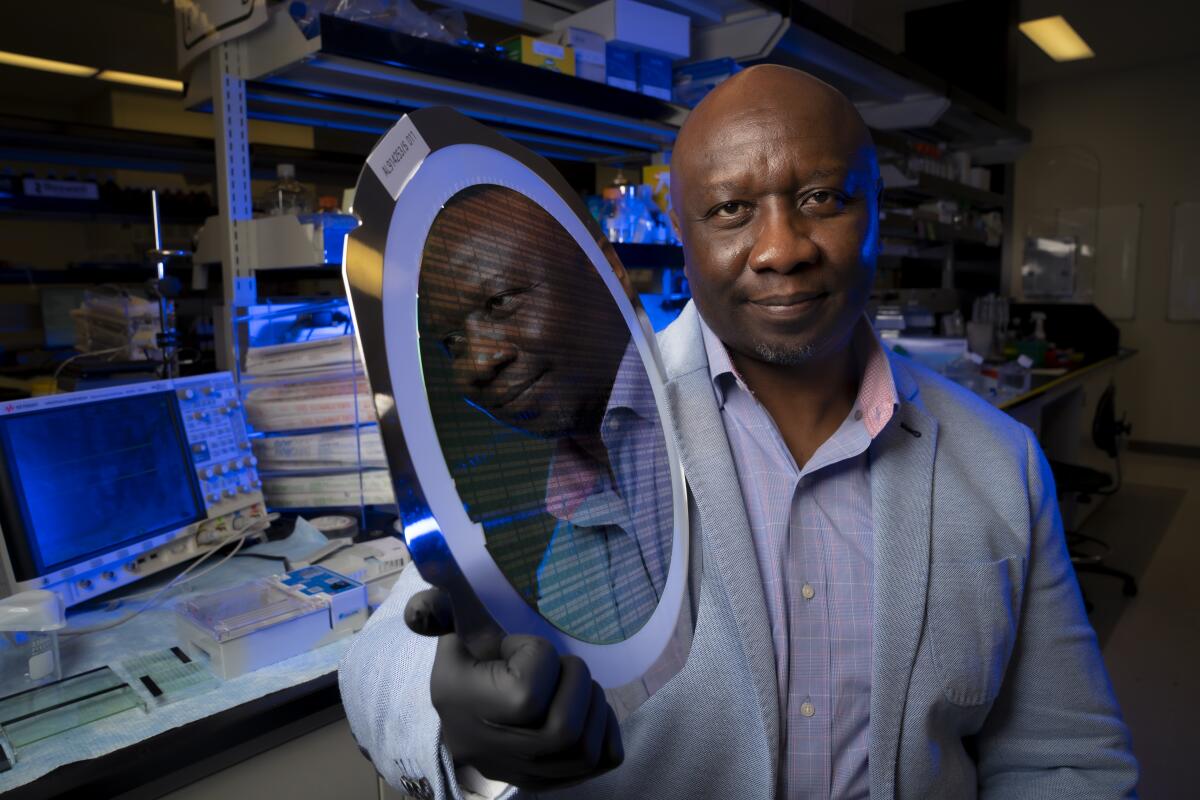

Given those challenges, it’s perhaps no surprise that Paul Mola is one of the only Black biotech CEOs in San Diego.

Mola heads Roswell Biotechnologies, a Sorrento Valley company working to develop low-cost, rapid DNA sequencing technology. He was born in Kenya and immigrated to the United States in his 20s. Before founding Roswell in 2014, his career included stints at Roche, Life Technologies and Human Longevity.

As one of the few Black people in the industry, he’s often felt like he had to work twice as hard just to get noticed: “There was never a moment when I thought otherwise, frankly.”

That once meant spending an evening holed up in the office preparing for a presentation and, rather than going home, checking into a hotel to take a quick shower before returning to work.

“It’s like a never-ending marathon where, unlike my peers, I am running on a muddy road,” Mola wrote in an email.

A new report from PledgeLA shows local venture capital firms invest in women, Black and Latino start-up founders at double the rate of the industry at large.

Mola spoke about his struggles and jump-started a broader conversation about race at his company during an internal meeting on June 26, about a month after the death of George Floyd.

Employees in masks gathered around an office table while others tuned in via Zoom. Some spoke about struggling with the knowledge that relatives had fought against the civil rights movement. Others shared their own experiences with discrimination.

At times, the room filled with laughter. Other times, with silence. Some speakers choked up.

Through it all, everyone kept returning to the same question: What do we do now?

In response, Mola said that Roswell is working on specific diversity targets for both the overall company and its leadership team: “We have an opportunity as an organization to be different, to showcase what is the right way to do diversity.”

For the moment, however, Mola is one of two Black employees at Roswell and the only Black board member. He estimates that of the company’s roughly 50 employees, about 10% are Black or Hispanic and 30% are women.Accountability for change

Historically, there has not been much data tracking diversity in the local biotech workforce. Biocom, a San Diego-based California life science trade group, issues annual reports charting the industry’s economic footprint in San Diego and statewide.

These reports don’t look at diversity. But they tout that the average San Diego life science employee earns about $130,000 a year. Median household income for Black households in San Diego was nearly $55,000 in 2018, according to the Center on Policy Initiatives, a nonprofit group focused on economic justice.

“I think we’ve got a lot of work to do,” said Joe Panetta, Biocom’s president and CEO.

National data show that this isn’t just a local issue. The Biotechnology Innovation Organization, or BIO, a national trade group, issued a January report that 66% of biotech employees who disclosed their race were white, 24% Asian, 6% Hispanic and 4% Black. Those numbers shift substantially at the CEO level, where 88% of company heads are white, 5% Black, 3% Asian and 3% Hispanic.

Mostly overlooked in the “Animal Crossing” craze, “Treachery in Beatdown City” is a game in which you fight racists. Behind its humor and retro look is bracing political commentary.

In 2017, the group issued target goals for increasing gender diversity among biotech leadership roles and board seats. Currently, women occupy 30% of executive spots and 18% of board seats. BIO aims to have women hold 50% of biotech leadership roles and 30% of board seats by 2025.

At the time, the organization did not issue similar goals around racial and ethnic diversity.

“We really hadn’t fully put our arms around issues of race,” said Dr. Michelle McMurry-Heath, BIO’s new president.

That seems poised to change under McMurry-Heath’s leadership. In June, she became the first Black woman to head the organization. She says that BIO will soon issue a range of diversity-focused plans, ranging from promoting diversity among clinical trial patients to making sure that companies can easily find candidates from underrepresented groups when it’s time to fill an open position.

Hunter might one day be one of those candidates. His heart disease research project has reinforced a passion for turning scientific discoveries into new treatments and medical devices.

Once he graduates, he says, he could see himself joining a startup (or possibly starting one) or a biotech or pharmaceutical company, and “even moving on to the C-suite eventually.”

“Through hard work,” he adds.