Will your town thrive or perish? The fate of millions is in your hands. Or so it seems. It’s your turn in SimCity

With the anniversary of SimCity, we dug into our archives for our coverage of the iconic game.

The mayor needed a martini: Frazzled freeway commuters were shooting at each other, rioters were pillaging the downtown and — better make that two martinis — Godzilla was stomping skyscrapers and factories.

And this was a good day.

In SimCity, where any idiot can run the government (just as in real life), disaster inevitably lurks right around the corner. Still, there’s a certain charm to this computer-game village: Embezzling is easy, power absolute.

“You feel like a god, controlling the destiny of all these people,” says Larry Bright, 42, of Arcadia, who with a million other pseudo-mayors has made SimCity one of the best-selling electronic games ever.

Some players become so engrossed in ruling their own towns — or overseeing one of SimCity’s built-in metropolises, such as San Francisco after the 1906 quake — that they forgo sleep and meals.

Others look for more esoteric approaches: A Rhode Island newspaper, for instance, persuaded five Providence mayoral candidates to play a round. The victor went on to become mayor.

In Michigan, the winner was Godzilla. Columnist Chuck Moss of the Detroit News let SimCity’s giant lizard run wild through the game’s “Detroit 1972” scenario, then compared the results against the real-life performance of Mayor Coleman Young. His conclusion: Detroit would have been better off with the monster.

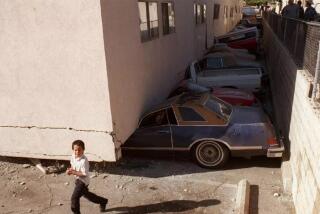

The game is also turning up in school and university classrooms. And one city planner says it might even hold a lesson for post-riot Los Angeles.

For most players, however, the goal is much simpler: Create a city from scratch or try to solve the problems of a built-in metropolis.

With tabula rasa towns, the game theoretically can last forever. The built-in towns have a specific problem to solve in a set amount of time. Rio de Janeiro’s, for example, is flooding caused by global warming. Mayors who fail are driven from town by an angry mob — led by their own mothers.

Meet Larry Borowsky, 29, a Denver resident and — in his spare time — mayor of Borisville. After guiding his town through a massive earthquake, fires and a disastrous plane crash, Borowsky now enjoys the kind of success that causes real politicians to salivate: sky-high poll ratings, a bustling economy and 200 consecutive years as mayor.

“But I’ve been waiting for Godzilla to strike,” he says, referring to one of many disasters that randomly befall SimCities.

On the computer screen, Borisville began as a 100-square-mile chunk of empty land, to which Borowsky added rail lines, highways, homes and factories. He set tax rates and opened police and fire stations.

Soon, miniature cars cruised the town’s roads, smokestacks belched soot into the sky and tiny football games could be seen and heard in the city’s gleaming new stadium.

“I became a total Republican playing this game,” Borowsky says. “All I wanted was for my city to grow, grow, grow. I put in nuclear power plants everywhere.”

Then came Borisville’s dark ages. A big quake wiped out 30,000 residents and fires swept through town. The mayor discovered that SimCity fire departments were virtually useless in the face of flames. “I put up a new station, but it just burned down,” he says. The only way to bring the blaze under control was to bulldoze around it.

The next disaster — a jetliner crash that leveled a swath of downtown — proved to have a silver lining. “The city center needed to be torn down, but politically it couldn’t be done,” says the poll-conscious mayor. “Then the plane crash came along.” When the smoke cleared, Borowsky put in a park, rerouted trains and reorganized his downtown. The once-languishing area prospered.

The lesson of Borisville could also apply in real life, says Brian League, a Los Angeles city planner and SimCity player: In the case of South-Central Los Angeles, for example, “a lot of pretty terrible development went up in the 1980s . . . like mini-malls and liquor stores. The riot allows us to revisit some parts of the city and maybe get some more appropriate developments.”

SimCity is realistic in other ways, too — enough so that USC, the University of Arizona and other colleges sometimes use it in urban-planning and political science courses.

At the same time, it’s fun enough to have sold 1 million copies since debuting in 1989 (500,000 for home computers and a like number for Super Nintendo) and it still lands regularly on the Software Publishers Assn.’s monthly top 10 sales charts. It’s also among Nintendo’s hit titles, according to Nintendo and Maxis, the Orinda-based manufacturer of SimCity.

“SimCity changed the face of computer entertainment software,” says Russell Sipe, publisher of Computer Gaming World magazine: It’s like an electronic erector set--more toy than game.

SimCity spinoffs, also from Maxis, include SimAnt (players try to avoid such hazards as insecticide, lawn mowers and a kid with a magnifying glass during their quest to drive the “yucky humans” out of the house), SimEarth (design your own planet) and the recent A-Train (the U.S. version of a popular railroad empire game from Japan).

But SimCity remains the company’s most popular — and addictive — product.

“When I first got it, I found myself skipping meals and staying up till 2, 3 or 4 a.m.,” says Arcadia’s Bright.

Borowsky felt similarly hooked: “I basically slept two hours less per night for several week — and I was happy to do it.”

Such reactions amaze the game’s inventor, Will Wright, who figured that nobody but architects and city planners would be interested.

Wright, 32, drew his inspiration for SimCity from a science-fiction tale, a neighbor and a computerized bombing mission.

The latter was part of another electronic game he designed, Nintendo’s Raid on Bungling Bay. For his next project, Wright wanted to reverse the concept: Instead of destroying cities, players would build them. Wright’s neighbor, an urban planner, supplied books and technical materials on how cities operate.

But the soul of the game derives from “The Seventh Sally,” the science-fiction story of a tyrant who is overthrown by his subjects and banished to an asteroid. Alone in space, the tyrant is given an electronic version of his old empire. But the electronic beings also overthrow him.

Wright was intrigued by the notion that electronic life could be real.

So he set out to devise a computerized world in which players could “suspend their disbelief.” He wanted an illusion so detailed that people would actually think their miniaturized cities are real, he says: “If a hurricane strikes, I wanted them to really empathize with the citizens.”

He also tossed in a few quirks and surprises for amusement. Like embezzling. The instruction manual doesn’t mention it, but if players hold down the shift key and type FUND, money pours into city coffers.

Another oddity is pre-Abraham Lincoln nuclear power. Players whose cities are founded in the 1800s don’t have to wait for Albert Einstein in order to construct a nuclear power plant. On the other hand, they shouldn’t be surprised when the thing blows up a century or two later: SimCity has a built-in anti-nuke bias. The game is also pro-mass transit.

Says Wright’s partner, Maxis president Jeff Braun: “We’re pushing political agendas.”

Some players discover another sort of politics: Despotism.

They cheerfully torture their SimCitizens with outrageous taxes, wasteful spending and nuclear power plants built smack in the middle of housing tracts. Or they press a few buttons and deliberately unleash tornadoes, floods and meltdowns. “Children typically love to blow up their cities,” Braun says.

In 1990, Rhode Island’s biggest newspaper, the Journal, set up a Providence-like town on SimCity and had five mayoral candidates try their hands at running it. One player, trying to knock down a condemned building, accidentally bulldozed an entire neighborhood. Another concentrated so hard on residential crime that thugs overran the downtown, driving away business.

Candidate Vincent Cianci, on the other hand, created room for more waterfront development and established a neighborhood police program that dramatically reduced crime. He also solved a housing crunch, avoided new taxes and left office with a small budget surplus.

What happened next might interest would-be successors to L. A.’s retiring mayor, Tom Bradley. Cianci, a former mayor who had quit in disgrace in 1984 amid charges of assaulting his estranged wife’s lover, won the real-life election by 317 votes. The SimCity gimmick might have helped, he figures, but that doesn’t mean electronic success guarantees electoral success.

“It’s only a game,” he says. “It’s only a game.”