Column: The end of the unemployment benefit boost shows how lousy work is in America

As has been well reported, the era of enhanced unemployment benefits for victims of the pandemic ended abruptly on Monday.

That was the expiration date of two federal programs, which provided an additional $300 a week in benefits on top of state-funded unemployment and extended the payments to workers not commonly entitled to unemployment coverage, such as gig workers and the self-employed.

The expiration affected about 9 million workers and their households. The Biden administration chose not to fight to extend the benefits.

We don’t have a work ethic problem, but a care infrastructure and healthcare risk problem.

— Rebecca Dixon, National Employment Law Project

Its reasoning is that, with the economy recovering from the pandemic, other parts of the safety net — including a permanently expanded food stamp program and a child tax credit of up to $3,600 per child over the next year — would shore up family finances enough to cover the expirations.

But that’s a simplistic picture of a complicated landscape. To begin with, all unemployed people are not alike. Millions of workers have returned to steady jobs, but huge pockets of unemployment remain, due in part to low pay and circumstances that can keep people out of the labor market even if they want to return.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Employers and some politicians have portrayed the continued unemployment in sectors that have high demand for workers thanks to signs of a post-pandemic recovery — such as retailing and leisure and hospitality — as the product of worker laziness and excessive unemployment benefits. But they often fail to confront the truth that the jobs simply aren’t alluring.

Marriott, the world’s largest hotel company, says it’s struggling to fill 10,000 job openings at its 600 U.S. hotels. But its chief executive, Tony Capuano, acknowledged in an interview with the Financial Times that his industry’s reputation for low-paid, dead-end jobs had hampered recruiting.

“We’ve got to do a consistent job of sharing the narrative that it is in fact an industry segment where incredible careers can be built,” Capuano told the FT.

The narrative that good jobs are available for the asking also overlooks all the residual reasons that millions of workers can’t return.

Evidence mounts that some employers can’t find workers because they’re jerks.

“We don’t have a work ethic problem, but a care infrastructure and healthcare risk problem,” says Rebecca Dixon, executive director of the National Employment Law Project.

“Many child-care centers closed and haven’t reopened, so there’s not affordable, accessible child care, and we have folks with complex medical needs,” Dixon says. “If your children are under 12, they can’t be vaccinated. If you have an immunosuppressed person in your household, you’re worried about bringing COVID home.”

What seemed to be a strong jobs recovery this summer hit a pothole in August, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, when jobs increased by an unexpectedly meager 235,000, well below the monthly average of 586,000 this year. The culprit may have been the Delta variant of the coronavirus, which has caused some renewed business shutdowns and demonstrated that the U.S. recovery is not yet on automatic pilot.

Until Sept. 6, the government’s enhanced unemployment benefits papered over those persistent issues. But it’s gone now, even though the problems remain.

Government statistics point to a sharply improving job market, though one that still hasn’t fully recovered from the pandemic. (Many of the latest figures, moreover, reflect the market as it was before the Delta variant slowed the nascent recovery.)

As of August, the Bureau of Labor Statistics says, nonfarm employment had risen by 17 million since April 2020 but remained lower by about 5.3 million, or 3.5%, from February 2020, the last month before the pandemic struck.

Weakness was still apparent in retail employment, which lost 29,000 jobs in August; that sector is still 285,000 jobs shy of pre-pandemic employment. Restaurants and bars lost 42,000 jobs in August and remained down by 1.7 million jobs, or 10%, since February 2020, the BLS reported.

That’s despite notable improvements in worker pay in those sectors. Average weekly earnings increased by 5.4% in retailing (to an average of $18.70 an hour) and 12.8% in leisure and hospitality (to $16.60 an hour) in the year that ended in August. Both increases were higher than the average in the private sector.

But those increases are also building from a small base, as those sectors are among the worst-paid in the economy.

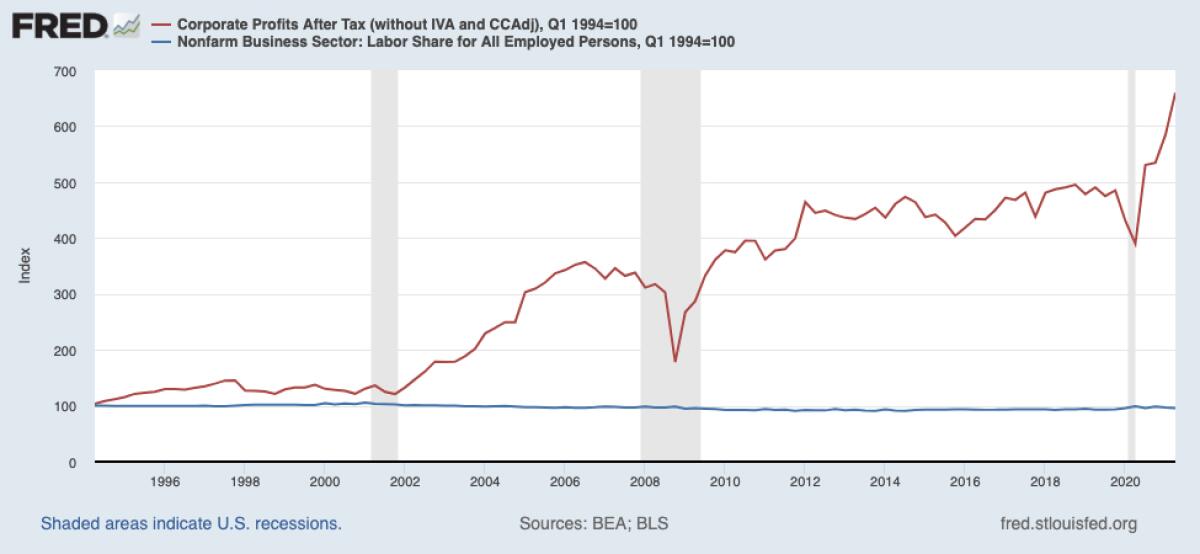

The increases also aren’t nearly enough to restore earnings to where they would be if hourly compensation continued to grow along with worker productivity, as it had until 1979, when the two trends diverged.

Where did the gains go instead of workers’ pockets? To corporate profits. Federal statistics show that, from 1994 through 2020, after-tax corporate profits increased nearly sevenfold, but labor’s share of the nonfarm economy fell by nearly 5%.

Unemployment programs are popular, especially in the aftermath of the pandemic, but they’ve remained the target of conservatives’ attack, based on the faulty premise that they contribute to worker indolence and malingering. There has never been strong evidence for that, and there still isn’t.

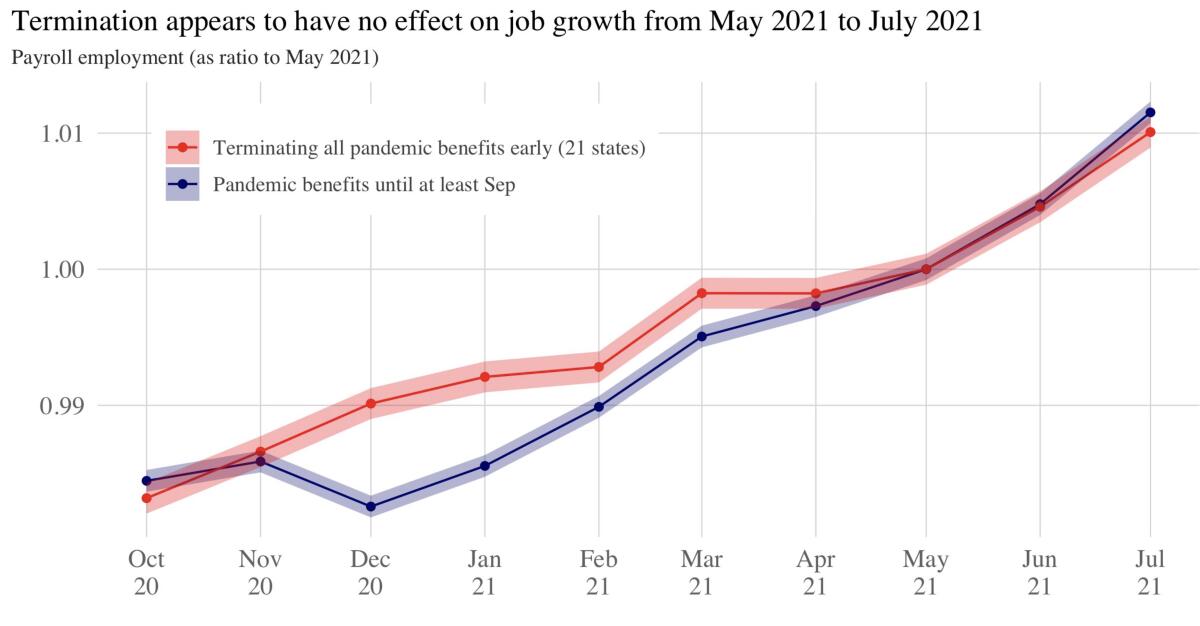

Nevertheless, the notion prompted 26 states, almost all red states, to end the federal $300 weekly benefit early, starting in June. That included 21 states that also canceled benefits to otherwise ineligible workers, including gig workers and the self-employed. The rationale in all cases was that the benefits were prompting workers to stay home instead of taking advantage of a recovering job market.

Economists searched assiduously for evidence of such an effect and for the most part came up empty. In fact, early surveys, including one by Peter Ganong of the University of Chicago, indicated that job growth was somewhat more robust in states that maintained the federal benefits than in states that cut them off.

Cutting off unemployment benefits early may even have resulted in GOP governors’ harming their own economies — a telling example of how ideology can be trumped by hard reality.

That’s according to a study by economists at Columbia, Harvard, the University of Massachusetts and the University of Toronto, who estimated that the early withdrawal of benefits resulted in a $4-billion reduction in federal dollars flowing to the withdrawal states, but only $270 million in increased earnings.

That caused a $2-billion reduction in consumer spending in those states, resulting in turn in what may have been “increased layoffs or reduced hiring,” the economists conjectured. Extrapolating from the early withdrawals, the economists warned that the Sept. 6 expirations were likely to lead to the creation of about half a million new jobs this month and next.

But because most of the about 4 million recipients losing unemployment insurance would take much longer to find jobs, they projected, “we could see around $8 billion in reduced spending during September and October.” The lost spending, they wrote, may limit overall job gains in these two months.

That merely underscores what has long been known about unemployment insurance: It’s not just a benefit for the recipients themselves but also the economy as a whole by preserving the spending power of laid-off and furloughed workers, which translates into more commerce, not less. This is something commonly forgotten by business owners and their political flunkies, if they ever think about it at all.

Proposition 22 is a revolutionary step in the influence of tech-based businesses in our daily lives in general and the lives of workers in particular.

To them, ending unemployment benefits was all about forcing workers to take the crummy jobs they had on offer. But if some 9 million Americans and their families suddenly have much less in spending money, what do they expect will happen to traffic in their restaurants, hotels and retail shops?

Evidence from the job market suggests that the pandemic phase of unemployment benefits helped workers by giving them a cushion — enabling them to survive through pandemic-caused job loss and also giving them the latitude to consider new career choices and even to launch their own businesses.

The difficulty of filling traditionally lousy jobs may have begun to shift the balance of power in the employment world, as Wall Street financial commentator Barry Ritholtz observes. Businesses are being forced to invest more in labor. That could lead to the restoration of the middle class and even to a realignment of politics away from the lionization of wealthy business owners as “job creators” and toward respect for workers as the foundational participants in business.

We’re not quite there yet, however.

The real drivers of hostility to unemployment insurance are still employers, who pay for the state components of the program through state taxes.

“Employers do not want to pay for the program, but because they do, they have all the power,” Dixon told me. “They basically strangle the programs in the states. It’s very hard to have adequate funding or benefits when the funding mechanism pits employers against workers.”

State-level control of basic benefits also explains why the range is so great among states, from the national low of $235 per week in Mississippi to a high of up to $1,234 for families with dependents in Massachusetts.

Dixon’s organization advocates a full-scale reconsideration of the unemployment insurance system. Among its prescriptions is for the federal government to set benefit standards — they don’t have to be identical from state to state but should bear some relationship to average wages in a state or region.

There should be a series of automatic triggers tied to the unemployment rate or some other statistical measurement of the job market, so that Congress doesn’t have to wait until an economic crisis is full-blown before providing help to the unemployed.

And there certainly needs to be better understanding of unemployment coverage as an anti-recession tool. The National Employment Law Project is calling for unemployment insurance to be included in the budget package beginning to make its way through Congress.

“The moment is now to put a down payment on fixing unemployment insurance for good,” Dixon says. “If it doesn’t start now, then once the economy is back, then UI becomes an afterthought. So it’s really crucial to start today.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.