Three theories of how this bull market will go off the rails

It’s that time of the bull market again, when everyone decides things beyond the realm of rationality have taken over in equities. Demand is brisk for an account of all the ways investors have lost their minds.

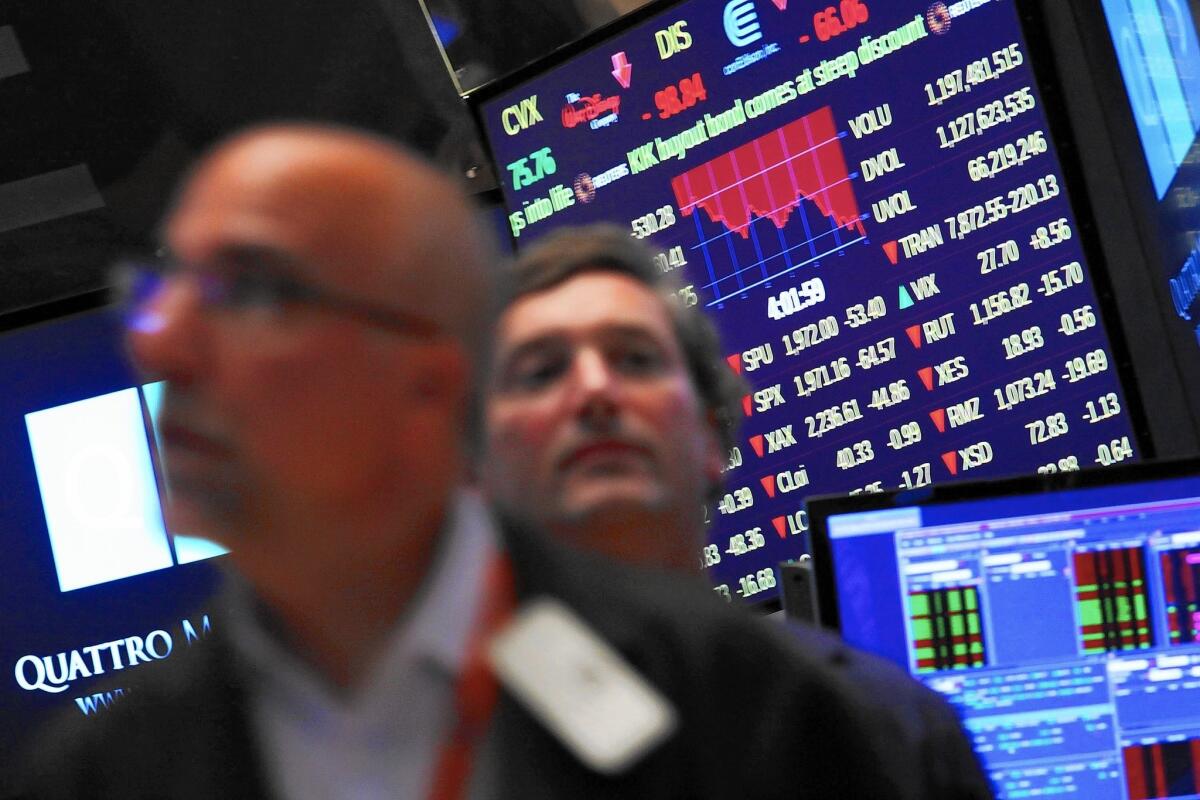

Concern is normal whenever the market is buoyant. When it’s 11 years into a massive rally and share values soar by $1 trillion in two weeks, skeptics come out of the woodwork. Records keep falling — the S&P 500 is setting one every 2½ days — while valuations fatten. It’s enough to make the staunchest bull wonder about a reckoning.

Dread is a natural human reaction to a market that appears to have inured itself to bad news. A global health panic, flat-lining economies in Europe, inverting bond yields — none has restrained the S&P 500, which is up eight of the last 10 days and 15 of 19 weeks. Forty days into 2020 and a third of the Nasdaq 100 is already up 10% — the list goes on.

Maybe it’s a bad look to complain when stocks surge. Yet lately it seems half of Wall Street must go on Twitter to protest each time the S&P 500 rises 1% or Tesla Inc. surges. For a rundown of all the stuff they say makes this leg of the advance untenable, read on.

Theory No. 1: Concentration

The stock market has ceased to be a report card on the broad health of American commerce and is instead being hijacked by four or five monopoly-like companies that basically can’t keep rising.

Wealth concentration in the market is well documented. Microsoft Corp., Apple Inc., Amazon.com Inc., Alphabet Inc., and Facebook Inc. now make up 18% of the S&P 500, a record. Combined, they account for half of the S&P 500’s gain this year, and one-fifth of its 400% rise since March 2009. When they break, so will everything else.

The 2008 financial crisis hit during millennials’ formative years — creating habits and fears that have kept many away from 2019’s stock market gains.

It may be sooner than you think, too, with regulators stepping up scrutiny. This week, the Federal Trade Commission issued orders to the five companies for information on past acquisitions. Even that couldn’t keep them from rallying.

The counterargument is that concentration is always present. In 2020, it’s Apple, Microsoft and Amazon. In 1990, the top three S&P constituents — Exxon Mobil Corp., IBM Corp. and General Electric Co. — accounted for 8% of the S&P. In 1980, IBM, Exxon and AT&T Inc. made up 12%, data compiled by S&P Dow Jones Indices show.

“Tech has run up quite a bit, but it’s not as worrisome as it’s been in the past,” says Jeff Zipper, managing director at U.S. Bank Private Wealth Management. “From a valuation standpoint, we still like it.”

By the way, as big as the FANG stocks are, the S&P 500’s weighting methodology is not the reason for its success over the years. Since bottoming in 2009, an equal-weighted version of the benchmark has returned 605% including dividends. That’s 80 points more than the classic market-cap weighted index.

Theory No. 2: The Fed

The stock market has ceased to be a report card on the broad health of American commerce and instead is being manipulated by the Federal Reserve.

Easy money and plentiful liquidity are the market’s drug, and when they’re taken away, withdrawal will be rough. Financial conditions are historically loose and monetary policy accommodative, and now the central bank is pumping billions of dollars’ worth of liquidity into financial markets to keep short-term funding markets tame.

No doubt Fed largess has played a role throughout the bull market. What’s worrying people now is the Fed’s efforts to prop up the repo market by buying billions of dollars of Treasury bills, which Chair Jerome Powell is at pains to categorize as unstimulative. Still, one strategist says every percentage-point increase in the Fed’s balance sheet has corresponded with a 1% gain in the stock market.

“There’s tons of liquidity out there, it’s driving the market higher,” Shawn Matthews, the chief investment officer of Hondius Capital Management and former Cantor Fitzgerald CEO, told Bloomberg Television. “People will always look for the extra 3 to 5% at the top. I would rather let someone else take it and move on.”

Just as many find the theory preposterous. Neel Kashkari, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, told “QE conspiracists” on twitter that he doesn’t see the connection. Dennis DeBusschere, Evercore ISI’s head of portfolio strategy, says the relationship between changes in the Fed’s balance sheet and the S&P 500 is near zero, and the latest stock rally is consistent with improving economic data and earnings.

“This can go on until it doesn’t — the expansion here can continue,” said Chris Gaffney, president of world markets at TIAA. “I don’t think investing in this equity market at this point is crazy. We still have good fundamentals supporting these equity prices.”

Theory No. 3: Passive funds

The stock market has ceased to be a report card on the broad health of American commerce and is more like a perpetual-motion experiment fueled by self-fulfilling deposits into passive funds.

It’s a theory you hear a lot: that exchange-traded funds and other index products are fueling a bubble. ETFs from industry titans like Vanguard Group Inc. and BlackRock Inc. cost next to nothing to trade, are diversified similar to mutual funds, but are easier to jump in and out.

In August, assets in passively managed U.S. equity funds exceeded actively managed competitors for the first time in history. Already in 2020, mutual funds have fallen behind their passive competitors by a distance that will be hard to make up.

“After a big gain, you’ll see investors piling in and the momentum continues because of the fact that they say, ‘I may have missed out last year and it looks like it’s really running so I better get more money into equity markets,” said TIAA’s Gaffney. “Momentum, especially ETFs and index-type funds, have an impact.”

While the influence of passive money is rising, one should be prudent in blaming ETFs for the market’s problems. More than $3.6 trillion is invested across 1,600 U.S.-listed equity ETFs, data compiled by Bloomberg show. That’s a lot, but it’s still about 12% of the market cap of the S&P 500.

Investors put $161 billion into U.S. equity exchange-traded funds in 2019, the smallest inflow in seven years, as the S&P 500 gained 28% in the same time — its best year in six. An August 2018 study by Federal Reserve staffers listed the verdict as “unclear” and evidence “mixed” as to whether inclusion in indexes was likely to raise a stock’s beta, a measure of systemic risk.

“When you get into a market that’s driven by momentum plays and passive money, you can’t help but think that if the rally gets excessive, these factors set things up for a spill,” said Marshall Front, the chief investment officer at Front Barnett Associates in Chicago. “But does it mean you should sell your stocks and run away? Maybe fundamentals aren’t as strong as you wished, but they’re improving.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.