Column: Mitt Romney takes a dishonest swing at ‘Medicare for all’

It’s open season on “Medicare for all,” now that Elizabeth Warren has joined her Democratic rivals in the race for the presidential nomination in placing her reform plan on the table.

Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, weighed in on the topic with a tweet on Thursday that amounts to the strangest attack yet. What makes it strange is that Romney, inadvertently or unwittingly, makes the case in favor of Medicare for all, not against it.

Having implemented a precursor to the Affordable Care Act as governor of Massachusetts in 2006, Romney should know healthcare backwards and forwards. So it’s proper to ask: Why doesn’t he show it?

Here’s the tweet in its entirety:

“Prof. Warren’s Medicare for All fails the test: Countries with socialized medicine make their numbers work through limits on care, cost sharing, and higher middle class taxes. Pretending otherwise is inauthentic and disingenuous.”

Let’s examine the tweet’s major points. We’ll leave aside Romney’s immature dig at Warren by calling her “Prof.” She hasn’t been a professor since 2013, when she became a U.S. senator — a role in which she outranks by seniority Mitt Romney, who only joined in 2019. Isn’t that so, Mr. Romney?

An anti-spending group issues some scary numbers about Medicare for all, but leaves out some key considerations.

We’ll also leave aside that he’s essentially calling Warren a liar, couching his accusation in the words “inauthentic and disingenuous.” (Merriam-Webster on “disingenuous”: “lacking in candor.”)

But what system is Romney describing when he writes of “limits on care, cost sharing, and higher middle class taxes”? It’s not “socialized medicine,” whatever that is. It’s the current system in the United States.

America’s healthcare system is shot through with limits on care, imposed not by government ukase but by private insurance companies and fundamental economics.

The insurers dictate what procedures patients may undergo, how long they can stay in the hospital or receive outpatient therapy, and whether their prescriptions are covered.

For a glimpse of how this works, consider the experience of hepatitis C patients after the introduction of the miracle cures Sovaldi and Harvoni by the drug company Gilead Sciences. Gilead set the price of the 12-week treatment at nearly $100,000, a price so high that insurers rationed the drug to patients to save money.

The giant insurer Anthem, for instance, designated the treatment as “medically necessary” and, therefore, eligible for coverage only for patients with advanced liver disease.

That cut the demand from its customers way back but was clinically upside-down — patients in the early stages of the disease, including those without symptoms, were the people who would benefit most from the drugs and whose cures would yield the greatest long-term savings. Those with advanced symptoms could in some cases be too sick to get more than minimal benefit.

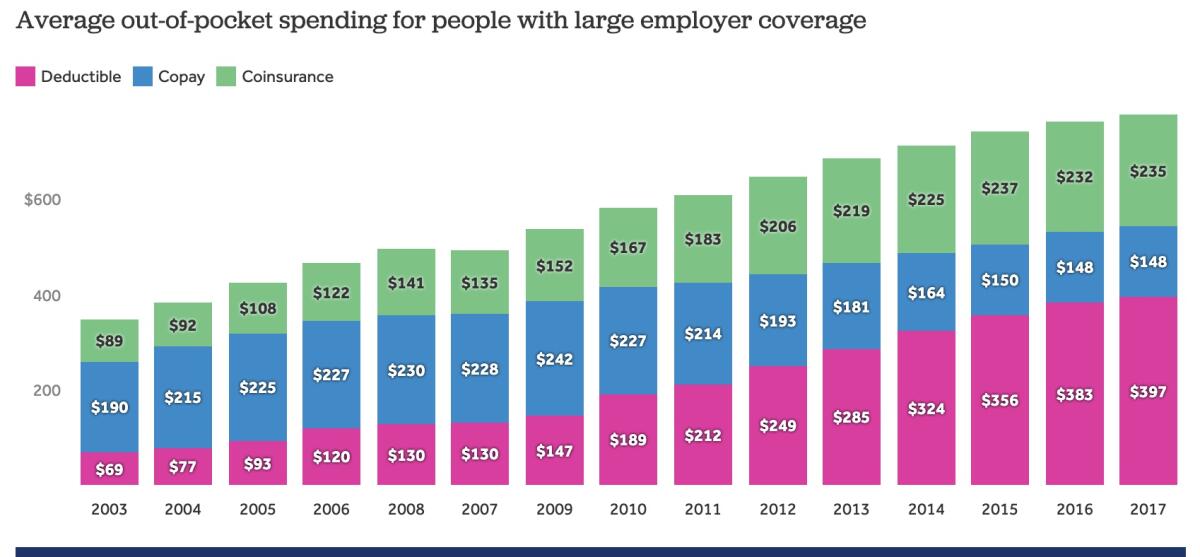

Cost-sharing? Anyone with employer group insurance or coverage from the individual market knows how deductibles have soared over the last couple of decades. In case Romney missed the memo, the Kaiser Family Foundation reports that the average deductible for single coverage in the employer-sponsored market has risen from $303 in 2006 to $1,396 this year.

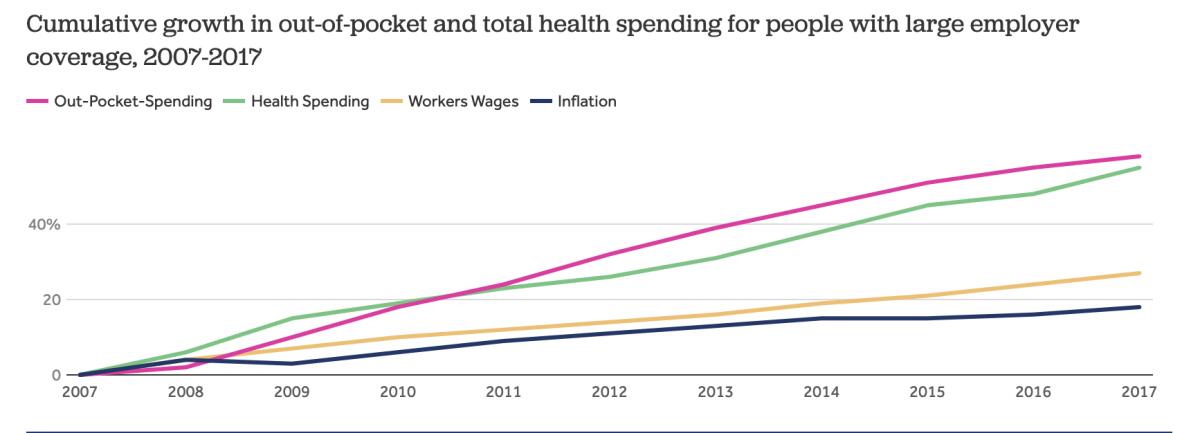

That’s just one element of higher cost-sharing. Out-of-pocket spending, including deductibles, co-pays, and cost-sharing percentages, has vastly outpaced inflation and the rise in wages over that period.

Michael Hiltzik: Should Mitt Romney take his Medicare?

The Kaiser Family Foundation calculates that the average out-of-pocket bill per enrollee rose from $348 in 2003 to $780 in 2017. To manage their ever-increasing insurance costs, employers have shifted higher percentages of premiums to their workers, too.

Whatever one wishes to label them, those costs are an effective tax on the middle class. Workers also are burdened with dealing with the administrative complexity of the healthcare system through time lost dickering with insurance claims agents and managing other lunacies.

One can argue about the size of the toll this takes on the middle class and how much of a role medical expenses play in household bankruptcies, but consider the findings of a joint Kaiser Family Foundation/Los Angeles Times survey this year:

Even among consumers covered by employer plans, “four in 10 report that their family has had either problems paying medical bills or difficulty affording premiums or out-of-pocket medical costs, and about half say someone in their household skipped or postponed some type of medical care or prescription drugs in the past year because of the cost.”

Another 17% said they’ve had to make what they feel are difficult sacrifices to pay healthcare or insurance costs; “for some, the sacrifices they report making are extreme.”

Medicare-for-all plans such as those proposed by Warren and Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., attempt to address these manifest flaws in the American system. They would shift the premiums and cost sharing now paid by consumers, employers and government programs into a single government bucket.

Both proposals acknowledge that extending coverage to the millions of Americans who still don’t have it and expanding services to cover what Medicare currently neglects would require new revenues.

Sanders and Warren fill the gap in different ways. Both would reduce payments to doctors, hospitals and drug makers and raising taxes. Warren says she can meet the bill by raising taxes exclusively on the wealthy.

Whether her math would work is subject to debate, but nothing she has proposed is entirely outside the realm of possibility. It’s best to treat both her proposal and Sanders’ as frameworks for further discussion, since they’re inevitably subject to the push and pull of the legislative process.

Romney could contribute to the discussion if he wished. But his gibes at Medicare for all don’t add up to a serious contribution. Criticizing countries with “socialized medicine” for the restrictions, costs and taxes that are in fact the paramount flaws of the American system prompts the question: Is he ignorant about American healthcare, or dishonest? (Excuse us: “disingenuous.”)

After managing a major state’s transition to healthcare reform, he couldn’t be ignorant. The only possible choice is the second.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.