Column: A brilliant economist diagnoses the U.S. healthcare system — from beyond the grave

- Share via

When the economist Uwe Reinhardt died unexpectedly in November 2017, his colleagues and followers lamented the silencing of one of the most penetrating, objective and effective voices in the healthcare debate.

They didn’t know the half of it. With the posthumous publication this month of his final work, a book entitled “Priced Out: The Economic and Ethical Costs of American Health Care,” Reinhardt’s reputation for cutting to the quick of the issues in U.S. healthcare reform is only enhanced. The book should be required reading for anyone who professes to have an interest in the debate — economists, journalists, legislators, doctors and patients.

Reinhardt, who spent his academic career on the Princeton faculty, may be best known for his seminal article on the reason for America’s outlandish spending on healthcare compared to every other developed country. Published in the journal Health Affairs in 2003, it was headlined, “It’s the Prices, Stupid.”

To what extent should the better-off members of society be their poorer and sick brothers’ and sisters’ keepers in health care?

— The late economist Uwe Reinhardt

In the article, Reinhardt and his co-authors explained that although Americans had fewer hospital admissions per capita and shorter stays per admission than residents of other countries, they paid more per admission and per day. The U.S. also paid the highest prices, by far, for drugs.

The culprit was the private insurance sector, which played a much larger role in America than in other countries; the public sector, represented here mostly by Medicare and Medicaid, was roughly as cost-effective as public health programs elsewhere. (An updated version published this year by Reinhardt’s co-authors —“It’s Still the Prices, Stupid” — came to the same conclusion.)

The Sutter Health and dialysis monopolies show why America can’t get healthcare costs under control.

Yet “Priced Out” raises an even more important point — that a chief obstacle to enacting sensible healthcare reform in the U.S. is our refusal to state the political issue squarely. As Reinhardt writes, it’s this: “To what extent should the better-off members of society be their poorer and sick brothers’ and sisters’ keepers in health care?”

To Reinhardt, this question is “the elephant in the room no one likes to mention.” Although it’s the fundamental ethical question underlying the healthcare debate, “we have never been able to reach a politically dominant consensus on the distributive social ethic that should guide our health system, because we dare not confront that question at all.”

Every other developed country has long since pondered this fundamental question and concluded that healthcare is a social good that should be “available to all on roughly equal terms,” Reinhardt writes, though the method of delivery varies from country to country.

Bernie Sanders has triggered another debate over the frequency of medical bankruptcy, but he’s mostly right.

Instead, we’re distracted into addressing the question in what Reinhardt calls “camouflaged form”— whether to “repeal and replace Obamacare,” for example or whether to allow premiums for seniors to be five times higher than for young adults, or three times higher.

My own favorite among these largely diversionary arguments is the one about whether the tax increase Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren would institute to pay for Medicare for All will hit the middle class or not. Here’s a pro tip: The American healthcare system imposes an enormous tax burden on the middle class today; getting to a system that provides universal healthcare is the point.

As Reinhardt documents, the American system as it exists essentially rations healthcare by income class. This isn’t always easily discernible because the system is “exceedingly complex and almost beyond human comprehension.”

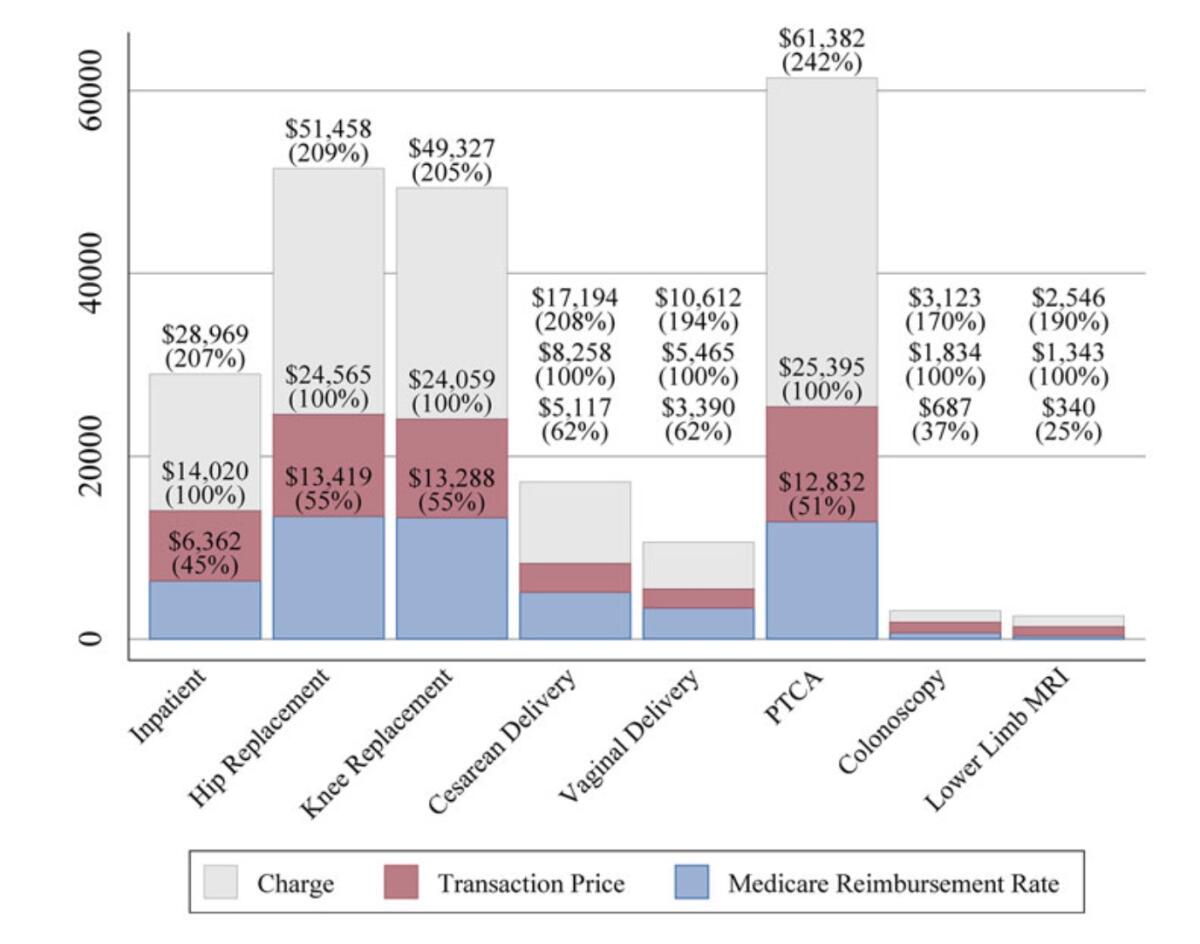

Its fragmentation into untold private and public payers and public and profit-seeking providers makes it impossible even to determine what a specific procedure costs. Reinhardt shows this by referencing a study by the Health Care Pricing Project that found the average hospital list price for a hip replacement — one of several procedures tracked by the study — at $51,458, the average insurance-negotiated price at $24,565, and the price paid by Medicare at $13,419.

Variations like this make a mockery of the conservative mantra that the key to lowering healthcare spending is to give patients more “skin in the game” via higher deductibles and co-pays. The idea that this will prompt patients to shop around for the best deals “has been a cruel hoax,” Reinhardt writes. In truth, they enter the healthcare market “like blindfolded shoppers pushed into a department store ... to shop around smartly.”

This “consumer-driven healthcare” idea is just another diversion to keep Americans from seeing the fundamental issues of the system clearly.

The cost of specific procedures may be opaque to the average patient, but there is no question that on average, Americans are vastly overpaying for their services. No country approaches the more than 18% of gross domestic product the U.S. spends on healthcare. Switzerland, which may come closest, spent only 12.3% in 2017. But Americans actually spend less time with physicians and have fewer and shorter stays in the hospital than Europeans; they just spend more per visit.

Reinhardt attributes much of the difference to the insane administrative complexity of the American system, especially in the private sector. The costs are manifest. U.S. physician practices spent an average of more than $80,000 per doctor interacting with health insurers, according to a 2011 study. That was four times the cost incurred by practices in Canada, which has a single-payer system. As Reinhardt reports, the Duke University hospital system, which had 957 beds in 2017, employed 1,600 billing clerks.

There were a couple of endearingly all-American aspects to Tuesday’s announcement of a joint venture by Jeff Bezos of Amazon, Warren Buffett of Berkshire Hathaway and Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase to reduce healthcare costs.

That suggests that the vaunted joint venture by Warren Buffett, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and JPMorgan Chase’s Jamie Dimon looking for a magic bullet to solve the healthcare conundrum with a technocratic fix may be barking up the wrong tree.

The Affordable Care Act reduced the segmentation of American healthcare by income class by eliminating it from the individual insurance market, as it had been eliminated from the senior healthcare market by Medicare. But the political compromises embedded in the law to get it passed made it only a partial victory.

Through federal subsidies, the ACA protects most of its enrollees, those earning less than 400% of the federal poverty line ($103,000 for a family of four this year), from the impact of rising premiums. But individual buyers earning more than that threshold are fully exposed to rising premiums.

Republicans and other Obamacare critics “have successfully made the plight of this group” — about 10% of the Obamacare exchange customer base — “the focus of their criticism,” Reinhardt observes. “It is why they, and President Trump, argue that Obamacare is imploding.” But that’s simply untrue of the larger market segment receiving subsidies. “That market is not imploding.”

Reinhardt is withering about Republican ventures to erode the Affordable Care Act. The replacement bill passed by the GOP-controlled House under then-Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) in 2017 plainly “favored the rationing of health care ... by income class.”

Trump’s position on the notorious Texas-led attack on Obamacare would be disastrous for employer-sponsored health plans.

Although the elimination of the penalty for breaching the ACA’s individual insurance mandate was enacted by the GOP and signed by Trump after Reinhardt’s death, this book makes clear that his opinion would have been equally dismissive, for he argues that one Obamacare “fix” that would have been technically simple albeit “politically difficult” would have been to increase the penalty to ensure that more young and healthier Americans had an incentive to sign up for coverage.

In 2012, Reinhardt proposed a reform to the ACA that, mischievously enough, purported to give conservative critics of the law just what they said they wanted — the “freedom” to choose whether to join the Obamacare pool or scorn it. Aware that the ACA gave the critics an escape valve that allowed them to join the pool if they got sick (though they might have to wait as long as a year until the annual open enrollment window), the catch was that their decision to refuse it would be in effect for the rest of their lives.

Every American would have to decide by the age of 26 whether to accept the ACA’s community-rated premiums — that is, premiums set without regard to their health condition — or “take a chance on being uninsured” or entering a market with premiums based on their illness. If they chose to be rugged individualists, they could never change their minds.

If they did fall ill or get injured, Medicaid would cover them (“rugged individualists live in a society that does not like to see people dying in the street,” he observed) but any expenses they incurred would give the government a claim on their lifelong income and assets until the bill was paid off.

“Libertarians should like this arrangement,” Reinhardt smirked, figuratively. His insight was profound: The prospect of actually being at risk for all your uninsured medical expenses was likely to concentrate their minds and remind them that, when it comes to health coverage, we all really are in the same pool.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.