Column: Facing eradication, the bail industry gears up to mislead the public about its value

- Share via

Few businesses enjoy a reputation for providing a public service as inflated as the bail bond industry.

To hear bail agents talk, they’re virtually the only people who can protect innocent communities from violent chaos perpetrated by defendants let out of jail before trial. “The most effective form of release in terms of ensuring appearance at court were releases on a financially secured bail bond,” the American Bail Coalition, the industry’s trade group, says on its website.

In California, the business of issuing bail bonds for profit is under attack as it is nowhere else in the nation. With the signature of then-Gov. Jerry Brown on a bill dubbed SB 10 in 2018, the state outlawed cash bail for criminal defendants. SB 10 created a new system allowing judges much greater discretion in setting terms of pretrial release for all but the most violent defendants.

The bail system makes payday lending look like child’s play.

— Sen. Robert Hertzberg, D-Van Nuys, sponsor of SB 10

Other states have remade their pretrial systems to reduce the role of cash bail, but none has yet gone as far as California.

“Were SB 10 to become law, it would practically mean the end to the commercial bail industry in California,” Jeffrey J. Clayton, executive director of the American Bail Coalition, told me.

As my former colleague Jazmine Ulloa reported a few days after Brown signed the bill, the law “could spell doom for not only bail agents, bounty hunters and surety companies across the state” but also a nationwide industry currently collecting $3 billion in annual revenue.

Uber, Lyft and Doordash will spend $90 million to undercut a California employment law.

Is that a bad thing? Probably not.

SB 10 was inspired by the need to reform a pretrial detention system that tied defendants’ freedom to their ability to pay bail. “Unsurprisingly,” the ACLU observed in a 2017 report, “there is racial bias in determining who needs to pay and who does not, and in how high bail is set.” A 2017 report by a blue-ribbon panel to California Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye — the basis of SB 10 — found that the bail system “exacerbates socioeconomic disparities and racial bias.”

The system allows wealthy defendants to purchase their freedom by making bail; poor defendants are stuck in jail even on lesser charges because they can’t make bail that judges may deliberately set beyond their means.

This system magnifies their disadvantages. Beyond being stuck in insalubrious quarters, jailed suspects have less opportunity to assist in their defense than released defendants. They can lose their jobs or income while they’re incarcerated, and face greater pressure to plead guilty even if they’re innocent.

The bail industry is fighting back hard against SB 10. The 2018 law, which was to go into effect this month, has been put on hold by an industry campaign to pass a referendum overturning SB 10. The measure will appear on the November 2020 ballot.

“We think bail is a way for people to not have to subject themselves to state supervision during prosecution,” Clayton says. “We think bail is a fundamental constitutional right — judges should have the option, as should defendants.” Invoking a favorite conservative bogeyman, he complained that some anti-bail organizations are funded by George Soros. (Soros’ Open Society Institute has supported numerous initiatives aimed at curbing pretrial abuses.)

One wouldn’t be surprised if the industry’s referendum campaign features personal stories of moms and pops whose families have operated bail agencies for generations but now face extinction — that’s been the theme of the pushback against SB 10 virtually since the day Brown signed the bill.

As a picture of the bail bond industry, that’s flagrantly misleading. Although there are 3,200 licensed bail agents in California, the business actually is dominated by big insurance companies such as the $40-billion Japanese firm Tokio Marine, which provide the money for bonds and collect much of the profit.

Based on the principle that one can judge the size of an industry’s ox being gored by the scale of its spending on lobbying and politicking, the stakes in this fight are sizable indeed. Industry contributions to Californians Against the Reckless Bail Scheme, the referendum campaign, have totaled more than $3.5 million since 2018 — and the campaign is only just beginning.

As we have learned from bitter experience over the years, in California’s ballot initiative process, money talks.

The largest contributor, at more than $794,000, is Triton Management of Carlsbad, which is largely owned by the Oregon private equity fund Endeavour Capital and affiliated with Aladdin Bail Bonds, a national firm that is the largest bail agency in California.

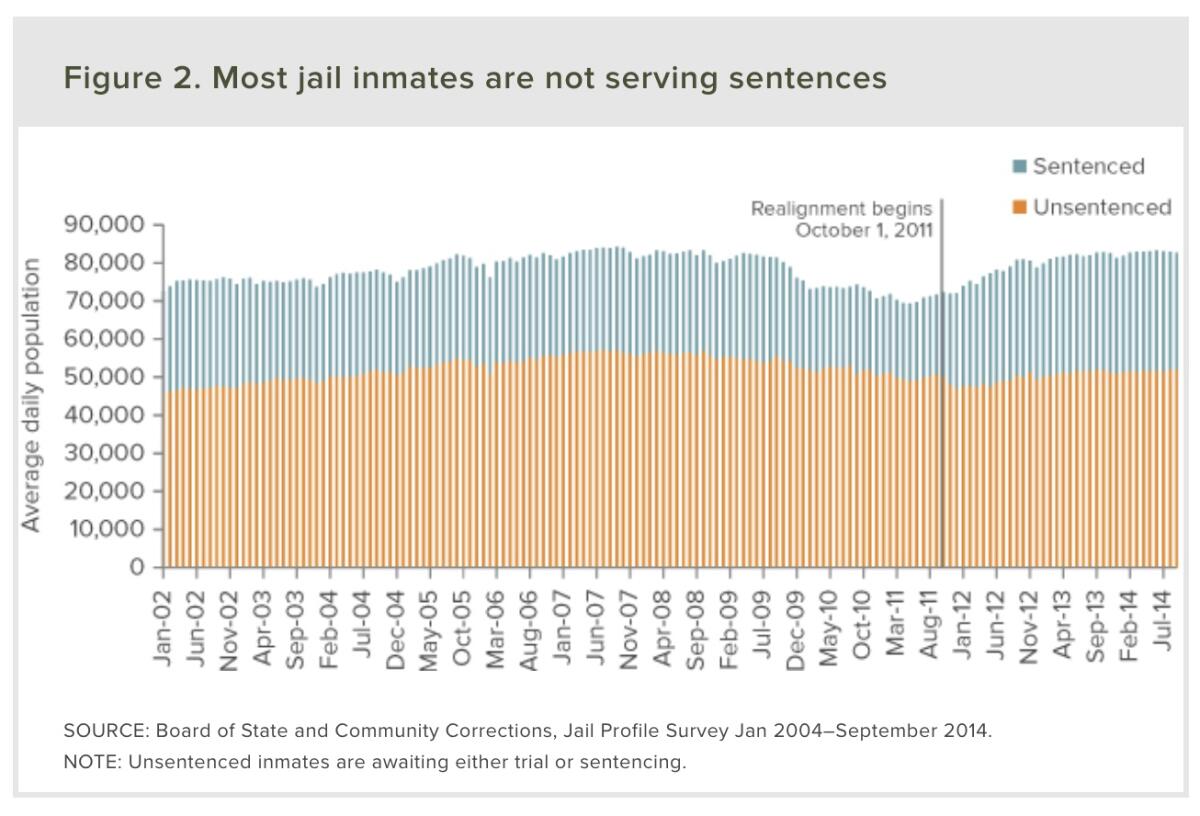

Bail also imposes immense costs on a state’s prison system. According to the Public Policy Institute of California, nearly two-thirds of the state’s more than 80,000 inmates were awaiting trial or sentencing in 2014. New Jersey’s pretrial reforms in 2017 sharply reduced the number of inmates in state prisons and cut the time that pretrial defendants spent in jail by half.

Defendants who can’t meet cash bail can negotiate their freedom through bail agents, who typically charge premiums of 10% — that is, $10,000 for a $100,000 bail. The premiums are nonrefundable, even if the charges are dropped, condemning low-income families to what might be years of repayment and subjecting defendants and their family members to nearly unlimited invasions of their privacy by their bail agents.

“The bail system makes payday lending look like child’s play,” the sponsor of SB 10, Sen. Bob Hertzberg (D-Van Nuys), told me.

A federal court lawsuit alleges that California bail agents have conspired to fix prices, setting premiums at 10%, discouraging price-cutting, and misleading customers into believing that 10% is a legally required rate. In fact, price cuts are perfectly legal. The lawsuit names 23 insurance companies and six bail agents, among others. The defendants have moved to dismiss the lawsuit, asserting that no such conspiracy exists.

Environmentalists allege that SoCal Gas funded an astro-turf group to make its case to the California PUC.

The image of bail as a surefire means of protection for society against habitual criminals or fugitives from justice is largely a fiction.

Among the most common misconceptions is that criminal defendants as a species are all potential absconders kept in check only by the prospect of forfeiting their bail money.

Figures on “failures to appear,” the technical term, are spotty, but those that are available suggest it’s nowhere as big a problem as it’s portrayed. The vast majority of defendants, whether out on bail or released on their own recognizance, show up for court dates. Nor do they go on crime sprees once they’re out on the street.

The U.S. Justice Department calculated in 2009 that 83% of all felony defendants released before trial appear for all court dates, and of the remainder, almost all returned to court within a year. Only 3% remained fugitives after that time.

The statistics don’t materially change in jurisdictions that have largely, if not entirely, dispensed with cash bail, such as the state of New Jersey and Santa Clara County in California. “Concerns about a possible spike in crime and failures to appear did not materialize” after New Jersey reformed its pretrial release system in 2017, the state courts reported this year.

Nearly 2 million electricity customers in California may not know it, but they’re part of a revolution.

In part, this reflects misunderstandings about why people miss their court dates. Studies show that a large proportion of failures to appear are due to defendants’ confusion over court dates, difficulty getting time off from work or securing child care so they can make it to court, or other such factors unrelated to a desire to evade justice.

“There’s an imprecision in the conversation about failures to appear,” says Lauryn Gouldin of Syracuse University law school, an expert on the bail system. “There’s a historic shorthand about ‘flight risk,’ but that doesn’t capture the majority of the problem. Most people aren’t going to flee the jurisdiction.”

Then there’s the impression that bail agents are so rigorously bound to their responsibility to forfeit the bail of an absconding defendant that they’ll move heaven and earth to get a client to court, a notion that has made bounty hunters into heroic figures of popular culture.

In fact, only a tiny proportion of bonded bail is ever forfeited, even when a client fails to show up. In California, state law imposes onerous procedures on courts seeking to collect bail from bond agents, such as notification requirements with tight deadlines.

The rules can raise the cost of collection to more than the recovery is worth. Meanwhile, clerical errors or missed deadlines by courts can release bail agents from their obligations. “Bail bond agencies are rarely held accountable to the courts when an individual fails to appear,” the San Francisco city attorney reported in 2017. Bail bond agencies routinely challenge forfeitures, and almost always succeed.

“You know how many checks has this company written to pay a bail loss?” Jerry Watson, a vice president and legal official at AIA, the Calabasas-based parent of three major bond insurance firms, told Mother Jones in 2014. “Not a single one.”

Those factors help make the bail business amazingly profitable. The California Department of Insurance, which regulates the bail industry, doesn’t maintain comprehensive statistics. But in an analysis of two bail insurers in 2014, the department determined that one had collected $51.9 million in premiums in 2012-13 and forfeited only $588,095, or 1.13% of premiums, and the other had collected $51.2 million in that period and forfeited only $282,484, a loss rate of 0.55%. (Loss rates on homeowner and auto insurance tend to run in the 60% to 70% range.)

Ending the cash bail system is merely the first step in reforming the pretrial detention system, criminal justice reformers say. Indeed, SB 10 has split the reform movement because of fears that it places too much discretion in the hands of judges.

“SB 10 was really about consolidating the power of judges and law enforcement in the pretrial context,” says John Raphling, a criminal justice expert at Human Rights Watch. The organization originally supported the bill but withdrew its support after amendments gave judges more latitude. That might “increase pretrial incarceration and even exacerbate racial and class biases in the current system,” Raphling wrote in a Times op-ed last year.

The bail industry is all but certain to use the split among reformers in its campaign against SB 10. At the moment, the campaign faces an uphill battle, though it’s at an early stage; a poll conducted for The Times by the UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies found that 39% of likely voters would keep SB 10 in place, against 32% who would reinstate cash bail and 29% who are undecided.

“We’ve learned two things,” the Bail Coalition’s Clayton told me. “People want bail reform, but they’re not real sure they want Senate Bill 10.” The industry will be spending heavily to make them sure they don’t.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.