Confucius Institutes: Do they improve U.S.-China ties or harbor spies?

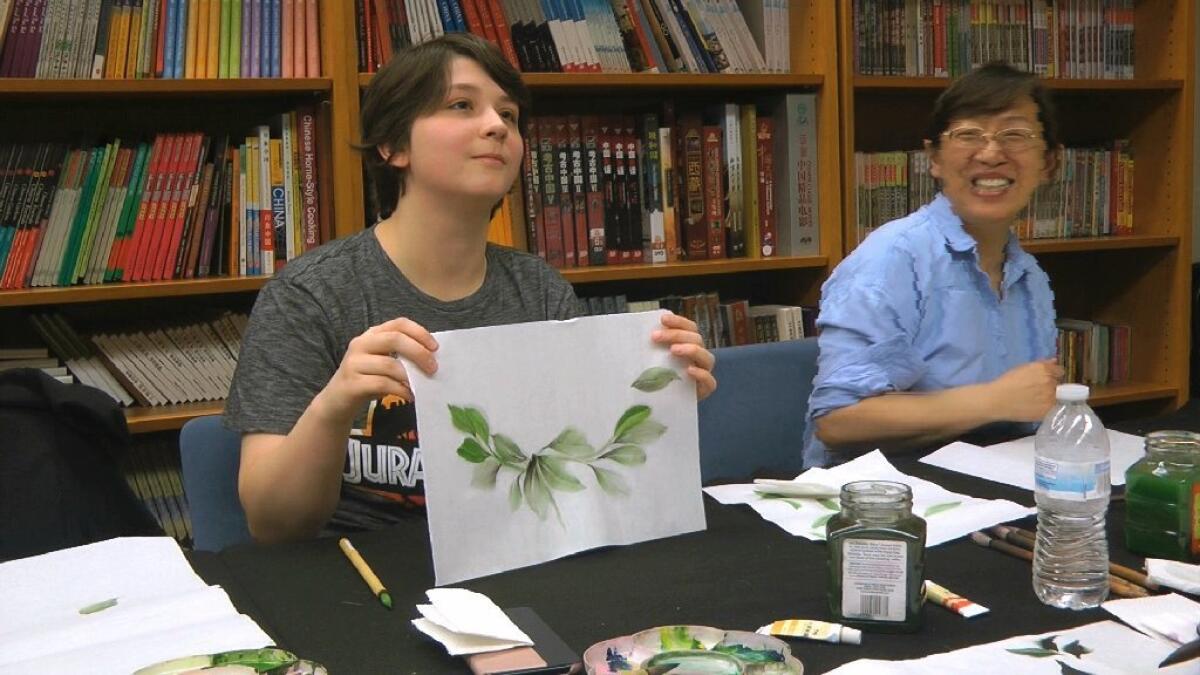

Reporting from Washington — Red hanging lanterns welcome visitors to the University of Maryland’s Confucius Institute, the oldest of about 100 Chinese language and cultural centers that have popped up over the last 15 years on American campuses, subsidized by millions of dollars from China’s central government.

Colleges once viewed these jointly funded institutes as an economical way to expand their language offerings — one that also could improve ties with China and, importantly, attract an influx of international students paying full tuition.

For the record:

11:50 a.m. Jan. 28, 2019This story says there are five Confucius Institutes in California. There are seven. The list left out UC Santa Barbara and Cal State Long Beach.

But U.S. officials are taking aim at Confucius and other Chinese government-supported programs, warning that universities have unwittingly exposed themselves to undue influence or even espionage efforts from America’s major political and economic rival. (At a dinner with business leaders in August, Trump reportedly stated that most Chinese students in the United States are spies.)

Last fall, four congressional investigators walked into the Confucius offices in Maryland and spent hours questioning staff, seeking detailed information about the program — including contracts, email exchanges and financial arrangements — that university administrators have kept confidential since the institute opened in 2004.

Amid a rise in Chinese cybertheft, officials have stepped up pressure on administrators to take greater precautions to guard against efforts to steal American technologies and research data.

The push, including the Senate investigation and a separate examination by Congress’ Government Accountability Office, reflects the broad shift in U.S. relations with China to one that has become more confrontational in recent years.

Robert Daly, former director for the University of Maryland’s initiatives on China, dismissed as “nonsensical” the suggestion that Confucius Institutes are hotbeds of espionage. But he and other experts agree that they clearly are instruments of the Chinese government.

Many university presidents, Daly said, went into the ventures believing that hosting a Confucius Institute would enable them to raise development dollars from China. Instead, he said, “what they find is that it doesn’t create leverage for them, but leverage for the Chinese Communist Party. … If the university does something that the Chinese Communist Party disapproves of, they may withdraw Confucius Institute funding.”

Opponents of the institutes — five are in California: at UCLA, Stanford, UC Davis, San Diego State and San Francisco State — also argue that the programs give Beijing a toehold in prominent American academic communities to influence attitudes and censor discussions of subjects sensitive to China, such as the Dalai Lama, Taiwan and human rights.

But some see the dark purpose as coming from the U.S. government.

“It’s such Red Scare tactics,” said Margaret Pearson, a political science professor at Maryland who specializes in China’s political economy.

The university refused to make Confucius officials available for comment. They also declined to allow The Times to view financial information about the program or its memorandum of understanding with Hanban, an agency under Beijing’s Education Ministry that funds the institute.

According to experts, there is no credible evidence that China uses Confucius Institutes as a front for espionage or other illegal activities. Members of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, chaired by Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio), and its staff and special counsel would not comment about the inquiry.

However, scrutiny of China’s efforts on college campuses has increased on many fronts.

FBI Director Christopher A. Wray warned universities last February not to be naive about Chinese spies in their midst and said the Confucius Institutes were on his radar. Vice President Mike Pence, in an October speech, accused Beijing of using organizations on campuses to monitor students for anti-China speech or activities.

Congress added a provision in the Defense Department’s 2019 funding bill that includes a restriction on foreign-language grants to universities that host a Confucius Institute. And a number of lawmakers, notably Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), have pushed for U.S. universities to cut ties with Confucius centers. Several schools in Florida and Texas, and most recently the University of Michigan, have moved to do so.

Named after the ancient philosopher-sage, the Confucius Institute was conceived by Beijing as a Chinese version of Alliance Française and Germany’s Goethe-Institut. The Confucius Institute launched in Seoul in 2004, and later that year China signed its first U.S. agreement with the University of Maryland’s flagship campus in College Park.

Today there are more than 500 Confucius Institutes around the world. The average program in the U.S. receives about $150,000 to $200,000 a year from China’s Hanban agency, said Gao Qing, director of the Confucius Institute U.S. Center, a kind of public relations and national support office for the institutes in Washington.

U.S. colleges also contribute offices and funds for operating the centers on their campuses.

Some public information is available through reports filed with the Department of Education, which requires colleges and universities to disclose foreign gifts and contracts of $250,000 or more in any given year. But the data can be sketchy, with some schools simply identifying the donor by country and others avoiding the disclosure threshold by having part of the funds transferred to a separate entity like a university foundation.

Gao said that Confucius programs have no agenda other than to promote the study of Chinese language and culture.

“The Confucius Institute program is benefiting the American people, no matter you’re pro-China or anti-China,” he said. “If you want to fight with China, you need people who can speak Chinese. And American education system is so lacking in funding.”

Gauging how much influence the institutes have on campuses is difficult.

At Maryland, professors remember that not long after the institute opened, a Confucius staff member questioned whether Taiwan-China relations should be part of a conference, given that it could upset the Chinese Embassy. That discussion went on anyway.

And when the Dalai Lama came to the school in 2013, the Confucius Institute pushed for a speaker from the Chinese Embassy to be scheduled about the same time to offer what turned out to be a counterpoint critical of the Tibetan leader, whom Beijing sees as a threat to its rule in that region.

“I saw it as a good opportunity for students to hear from both sides,” said Scott Kastner, a professor in the department of government and politics, adding that Maryland’s Confucius program is low-key and doesn’t have much influence on campus.

At George Mason, a public university based in Fairfax, Va., financial records and program details obtained through the Virginia Public Records Act show how the Confucius Institute has expanded on that campus and been used as a marketing tool and platform for outreach to the community. (The University of Maryland cited significant costs and possible delays in responding to a similar records request.)

In its first year of operation in 2009, George Mason’s Confucius program received $341,350 from Hanban, which was also responsible for providing teachers and a Confucius Institute co-director from George Mason’s partner university, Beijing Language and Culture University. Since then, annual funds from Hanban have ranged from $139,501 to $635,101.

In addition to language courses, George Mason’s Confucius Institute has supported or hosted adult education programs, as well as activities at local schools, museums and galleries. In October, George Mason extended its partnership with China for five more years.

Amid increasing scrutiny and political pressure, however, a number of universities, including Tufts in Massachusetts, are considering whether to continue their Confucius centers. Others say they have taken steps to safeguard academic integrity.

For major universities, it’s less about the funds Hanban provides than about the threat of soured relations with China and how that could influence the schools’ ability to recruit top-notch talent — as well as international students who pay full tuition.

There are more than 400,000 Chinese students and scholars at U.S. colleges and universities, nearly a fifth of those in California. One out of 10 freshmen accepted for the fall 2017 class at UC Berkeley was an international student. And as is the case for colleges overall, about one-third of Berkeley’s foreign students are from China.

In 2010, Hanban made a one-time gift to Stanford University of $4 million for a Confucius Institute, an amount matched by the university to fund an endowed professorship in Chinese culture and to support graduate fellowships, conferences and other programs.

Hanban doesn’t have a say in the choice of scholars or the graduate fellowships, said Richard Saller, Stanford’s dean of humanities and sciences who oversees the university’s Confucius Institute.

“Because the Hanban contribution is an irrevocable gift, they have no leverage to infringe academic freedom at Stanford,” Saller said in an email. “Nor have they tried.”

U.S. policy toward China shifts from engagement to confrontation »

As protesters fill streets of Venezuela, Trump recognizes opposition leader as rightful president »

Follow me at @dleelatimes

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.