Loss of mid-wage jobs hampers state’s growth

- Share via

On the surface, California’s job market is booming.

The state has now recovered all the jobs lost during the recession, and done so at a faster pace than all but five states.

The growth, though, belies a troubling imbalance. The fastest job creation has come in low-wage sectors, in which pay has declined. At the high end of the salary scale, a different dynamic has taken hold: rising pay and improving employment after rounds of consolidation.

Most distressing, middle-wage workers are losing out on both counts.

“People talk about it like an hourglass,” said Tracey Grose, vice president of the Bay Area Council Economic Institute. “There are fewer opportunities for people in the middle.”

Economists generally consider mid-wage jobs to pay between $15 and $30 an hour in California — encompassing a third of workers in the state. Those at the top end of that range, which amounts to about $60,000 a year, earn more than 72% of Californians.

Middle-wage stagnation can damage consumer spending, dent career mobility, stall home buying and exacerbate a poverty rate that’s already the highest in the country, economists warn. Those concerns are amplified in a state notorious for a high cost of living.

As more mid-tier jobs disappear, economists fear middle-class workers will be increasingly sucked into the ranks of the working poor. And they could crowd out those already working low-wage jobs, or drive their salaries down further.

“The long-term problem isn’t unemployment; it’s poverty,” said Stephen Levy, director of the Center for Continuing Study of the California Economy in Palo Alto. “It’s not jobs; it’s wages.”

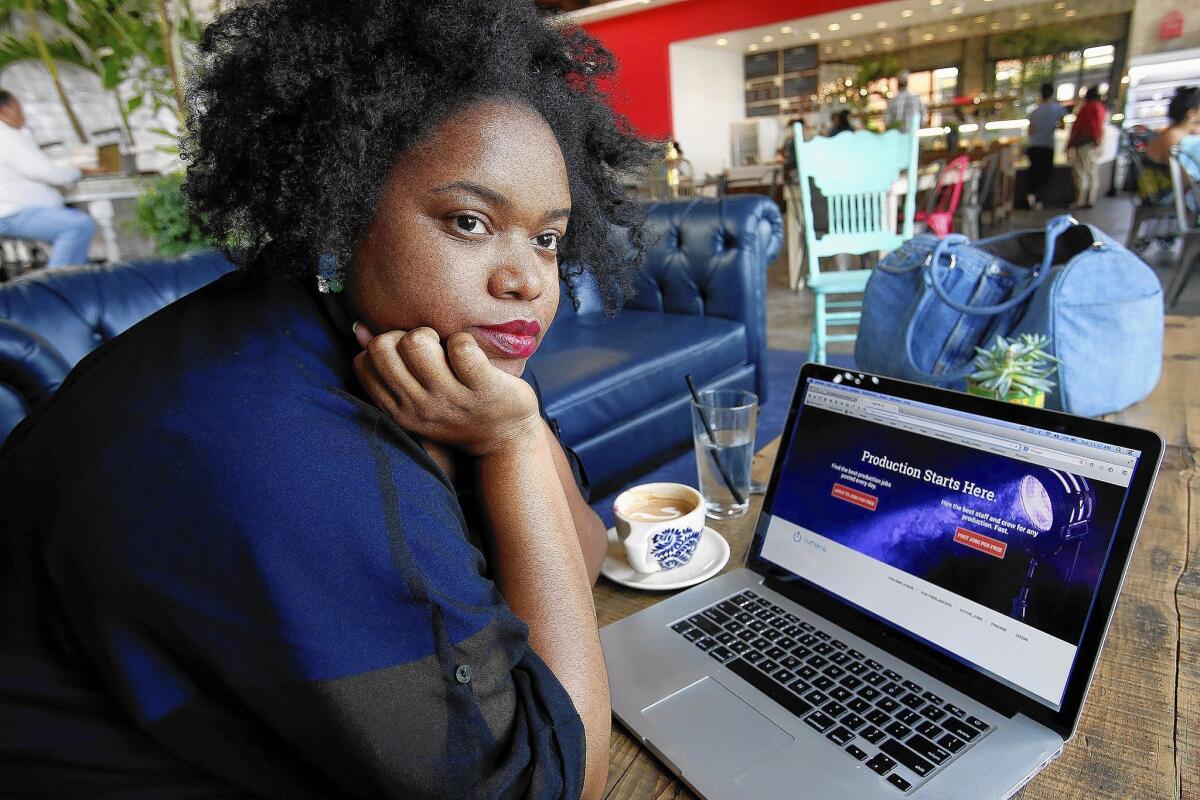

Valerie Colter landed a $1,000-a-week job, right out of college in 2005, as an executive assistant to a sitcom producer. She was laid off two years later.

She has struggled since then to make half as much. She did a stint as a transcriber for a reality show company, working overtime to bring home $525 a week. She earned $250 every other week as an Ikea cashier; $500 a week as a postproduction assistant; $600 a week organizing a footage library.

Since 2013, the Lake Balboa resident, now 31, has worked as a coordinator at a captioning company, where she earns $500 a week while struggling to pay off student loans.

“They can’t afford to pay me what I’m worth; they can’t even match the pay at my last job,” she said. “It makes me sad. I always thought that, in 10 years, I was going to be awesome. Now here I am, just trying to survive.”

Burdened with rising healthcare and rent costs, California employers aren’t keen to raise wages. Although salaries are rising in some higher-end fields, such as electrical engineering and information technology, that mostly reflects companies competing for top candidates from a limited pool.

But there’s a glut of low- and middle-wage job seekers: former executive assistants, manufacturing technicians, insurance agents and more. Those were the types of jobs companies spent the downturn merging, automating or cutting entirely as profit margins tightened.

Earnings for both low- and mid-wage Californians have been eroding for years.

For the bottom half of the workforce, real hourly wages are 6.7% lower than they were 35 years ago, according to a June report from UC Berkeley. Since 2003, median wages for workers shrank 7.2%. The only workers in that period to enjoy real wage gains were those in the top fifth of all earners.

For now, that means the lesser-paid employees aren’t a priority for many businesses, even those that are expanding as the recovery matures. Mid-wage employment suffered the deepest decline in the recession and is the only segment to continue falling even in the recovery, according to the California Budget Project research group. Inflation-adjusted earnings in that segment slumped 3.8% between 2006 and 2012.

In historically mid-wage industries such as manufacturing, fewer supervisory positions are available because so much of the work has been automated. The largest percentage of openings are low-paying, such as the $9- to $11-an-hour assembly post being offered by Kelly Services. The staffing agency will send the worker to a facility making consumer goods near Inglewood.

Low-wage workers have had trouble moving up the ranks since the recession; mid-wage workers have fought to hold their ground. Many skilled laborers have yet to earn the certifications or education that employers are increasingly demanding of applicants, said Genine Wilson, vice president of Kelly’s Southern California territory.

“They’re looking at lower-paying jobs as an entry point toward the jobs they want,” she said.

The disparity is especially stark when comparing the northern and southern parts of California.

Compared with the state as a whole, the Bay Area was more insulated from the downturn and bounced back faster. Three of the five U.S. counties with the highest weekly wage are there, led by San Mateo, where pay averages $2,724.

But in Southern California — which has more than double the number of jobs in the Bay Area — payrolls shrank faster and have recovered more slowly.

More than a million jobs will be created in the region between 2010 and 2020, and nearly half will pay less than $14.35 an hour, projects Levy, the Palo Alto economist.

Last year, average wages in Los Angeles County declined 1.9% — tying Jefferson, Ala., for 302nd place out of 334 large counties nationwide. San Francisco ranked 19th with a 3% increase.

Statewide, the middle class still makes up the largest chunk of households, but its share has shrunk since 2007, as it has for higher-earning households. Now, nearly a third of California households are in the bottom tier of the income range, up from fewer than a quarter.

The middle class helps shore up economic stability with its spending power, said Robert Kleinhenz, chief economist of the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corp. He said low-wage jobs have historically served as a gateway.

Recent proposals from legislators and economists to boost earning power have included training programs run by local employers, more infrastructure projects and minimum-wage increases indexed to inflation.

“If you have all three income levels in balance, there’s a theoretical ladder that lower-wage households can hopefully climb,” Kleinhenz said. “It helps to sustain the overall health of communities to know that there’s the possibility of moving up. That’s the American dream.”

Twitter: @tiffhsulatimes

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.