China’s state planner suggests using rare earths as leverage in U.S. trade war

China’s powerful planning body has threatened to use rare-earth element exports as leverage in the trade war with the U.S., in a sign of increasing tensions between the two powers.

Rare earths, a group of 17 metals with a variety of high-tech applications, are used in magnets, instrument displays and other components that go into everything from iPhones to missiles to electric vehicles and LED lighting. They are the one raw material of which China dominates global supply.

A tightening in Chinese export quotas a decade ago brought the limited supply of the little-known minerals to the attention of the international security community as a potential strategic threat.

Relations between China and the U.S. have deteriorated sharply since the countries failed to strike an anticipated trade deal in early May.

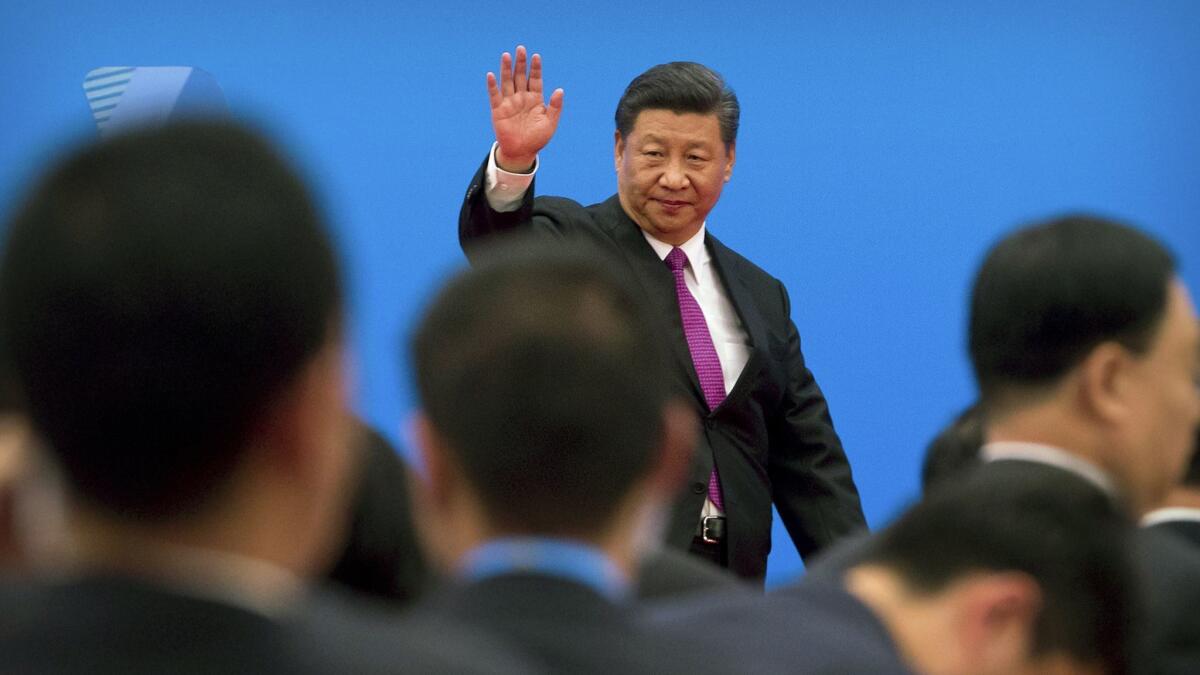

Last week, shortly after President Trump blacklisted the Chinese telecommunications firm Huawei, China’s President Xi Jinping visited a rare earths magnets firm in Ganzhou, in southeastern Jiangxi province. The move has been interpreted as the prelude to retaliation.

The National Development and Reform Commission, which oversees China’s economic policy shifts, highlighted the threat of an export cutoff in a bulletin.

“Will rare earths become China’s counter-weapon against the U.S.’s unwarranted suppression? What I can tell you is that if anyone wants to use products made from rare earth to curb the development of China, then the people of the revolutionary soviet base and the whole Chinese people will not be happy,” the notice read.

However, the commission stopped short of declaring any specific policies. China currently exports very few rare earths directly to the U.S. Intermediate products containing rare-earth metals go through a long production chain, mostly in China and Japan. Washington has identified the exports as a vulnerability and exempted the material from its tariffs.

Rare earths capture the attention of security strategists but in practice would be difficult to wield as a weapon. China first imposed export quotas on them more than a decade ago but dropped the quotas in 2015 after losing a case at the World Trade Organization.

It is not clear how it would regulate trade in intermediate or downstream products. The problem for China is that any new restrictions would cause damage to its recently developed industrial supply chains, which are dependent on foreign customers in the U.S., Europe and Japan. Any restriction would reinforce the notion that China was a risky source of supply.

Three state-owned mining firms have wrestled for control over the rich deposits around Ganzhou, in south-central China. Ganzhou stands at the edge of the Jinggangshan range, where the Chinese communists formed a revolutionary base before retreating on the Long March in 1934-35. Xi’s visit to the area last week symbolized self-reliance and determination in the face of the trade war, in the spirit of the Long March.

© The Financial Times Limited 2019. All Rights Reserved. FT and Financial Times are trademarks of the Financial Times Ltd. Not to be redistributed, copied or modified in any way.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.