‘Sons of Wichita’: A surprisingly nonpartisan look at the Koch brothers

In the demonology of the left, the Koch brothers are the archfiends.

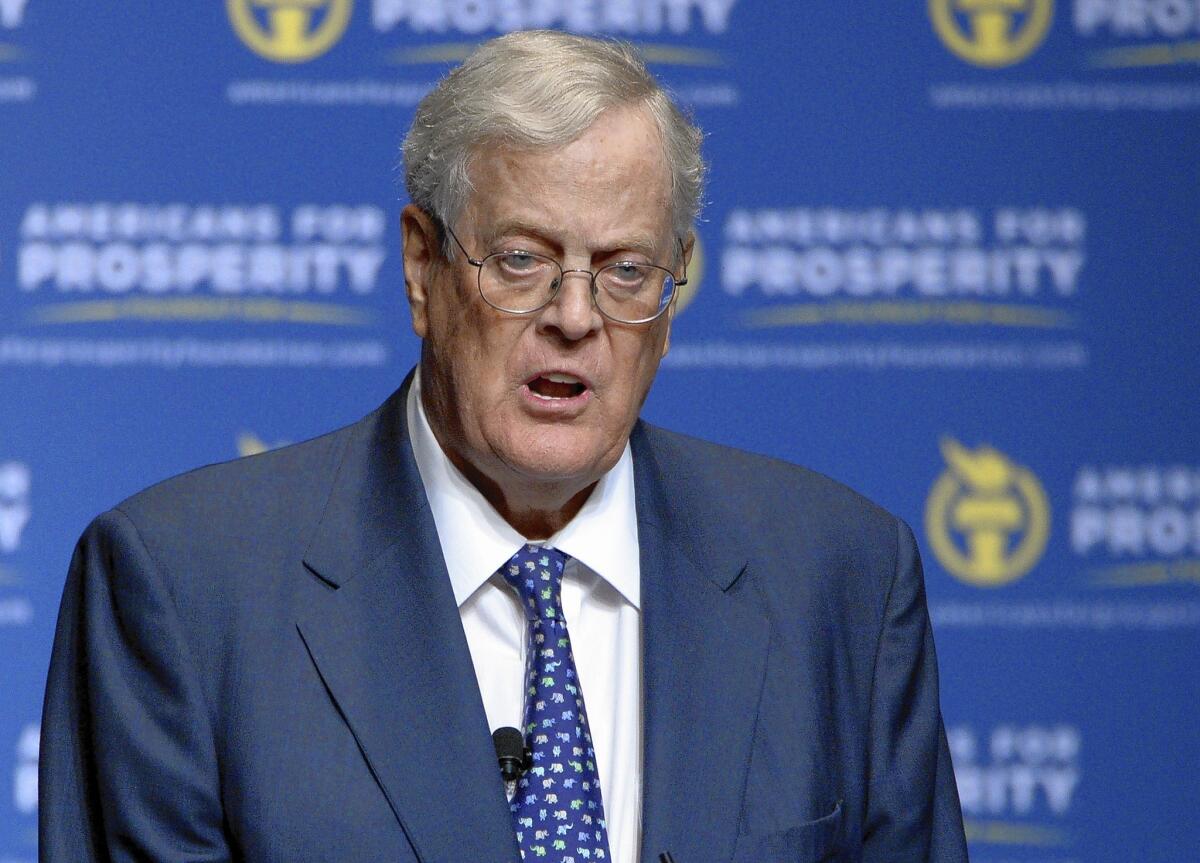

Fabulously rich, instinctively private — “secretive,” their enemies say — espousing libertarian convictions and with a determination to reshape America to fit their ideas, Charles and David Koch are easy to cast as cartoon villains.

Together, they are estimated by Forbes magazine to be the sixth-richest men in the U.S., worth $41.5 billion each thanks to their stakes in Koch Industries, a business empire spanning refining, pipelines, commodity trading, paper and Lycra.

In the 2012 election, they raised more than $400 million to oppose President Obama and other Democrats.

Harry Reid, the Democratic majority leader in the Senate, attacks them as “two power-drunk billionaires.”

An editor at Mother Jones, Daniel Schulman might have been expected to turn in a partisan hit job in his new book, “Sons of Wichita: How the Koch Brothers Became America’s Most Powerful and Private Dynasty.” The publisher is Grand Central Publishing.

Instead, he has done something much more interesting: looked past the mythology to write the first serious biography of all four Koch brothers, including Frederick, the oldest, and David’s twin, Bill. The result is an outstanding success: a real-life “Citizen Kane” that traces the lives of powerful men to their roots in childhood.

“Sons of Wichita” is also, to use a parallel cited by Charles and David Koch’s lawyers, reminiscent of the television show “Dallas”: an epic family saga of feuding brothers, wild parties, unlikely romances, espionage and a plane crash.

By the end, even the Kochs’ staunchest adversaries should have a more sympathetic understanding of the characters and motivations of the men they are fighting.

Combat is one of the book’s principal themes, beginning with the startling opening image of a teenage David and Bill battering each other with gloved fists by the side of a quiet road in rural Kansas, supervised by one of their father’s employees.

Fred Koch, the patriarch, was a successful businessman who prospered with a refinery equipment business in the 1920s and 1930s. He was, however, determined that his sons should not be made soft by luxury like the children of other rich men.

He insisted that they work on the family ranch to earn money, and Bill and David were encouraged to work out their differences with boxing gloves from the age of 5 or 6.

That bellicose spirit was to stay with them: At the heart of the book are the two decades of legal battles between Charles and David on one side and Bill and Frederick on the other for control of Koch Industries.

The bitterness of that battle, which apparently led to Charles refusing to shake Bill’s hand at their mother’s funeral, is characteristic of the intensity with which the Kochs have set about their business, their enthusiasms and their politics.

Schulman’s research is impressive, tracking down old college girlfriends and distant family members, but the evidence is often scanty, and the brothers themselves refused to cooperate, apart from Frederick, who appears to have granted a brief audience. Because Koch Industries is privately held, details of its operations are sparse.

A fascinating section on “market-based management,” Charles’ system for encouraging independence and entrepreneurial thinking among Koch Industries’ staff — expounded in his own book “The Science of Success” — is tantalizingly brief.

In the end, like Charles Foster Kane, the Koch brothers elude their biographer’s attempts to uncover their deepest secrets. The judgment from an anonymous relative that “everything goes back to the love they didn’t get” is a little too pat.

Even so, unless one of the brothers abandons the habits of a lifetime and tells his story to the world, “Sons of Wichita” feels as close to the truth as anyone is likely to get for a long time to come.

Ed Crooks is the New York-based U.S. industry and energy editor for the Financial Times of London, in which this review first appeared.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.