Using technology without losing humanity: Jon Favreau on his use of special effects

Jon Favreau’s movie career spans the technological gamut — from the fly-by-night feel of “Swingers” to the effects bonanza of the “Iron Man” franchise.

Today, he has digital tools for filmmaking he thought impossible just a few years ago. But none of them matter, he said, if they’re not deployed with humanity.

The longtime actor, director and producer said technology can be isolating and offer escapism. But when it truly succeeds, it enables audiences to feel an empathy that simply wasn’t possible before.

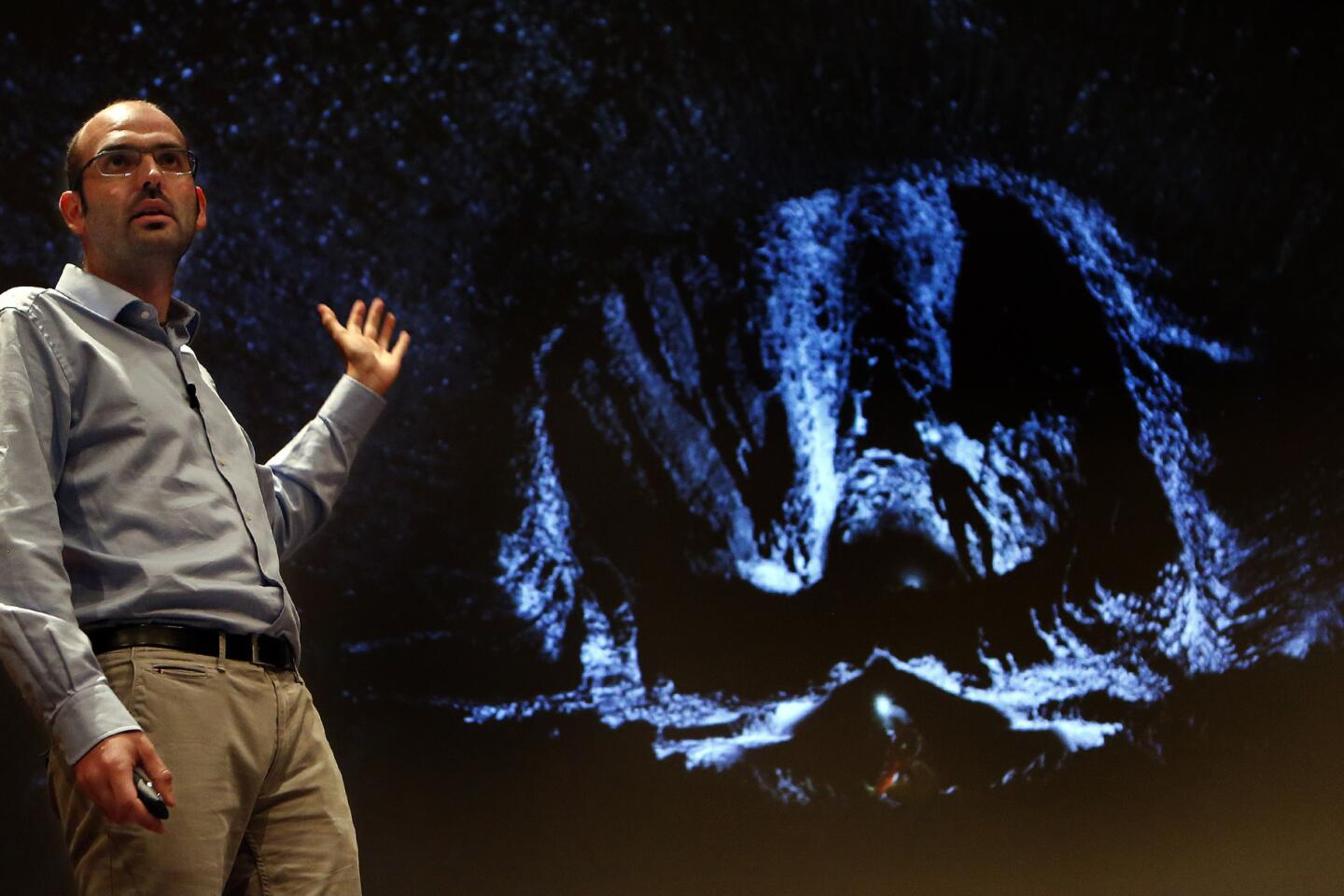

“Storytelling is a human endeavor,” Favreau said at a Times summit on innovation Monday at UCLA. “Technology seems like it distracts from that, but when it does its job, it’s heightening the connection.”

Favreau was one of about a dozen speakers at the summit called “The Big Idea: Innovating for Tomorrow,” which explored how technology and new ways of thinking are enhancing storytelling, securing a healthier food system and widening the scope of space exploration.

Among the other speakers were chef and author Alice Waters, virtual reality studio co-founder Neville Spiteri and filmmaker Werner Herzog, who discussed how he made his recent documentary on volcanoes, “Into the Inferno” (“It’s prudent to film as fast as you can and then flee as fast as you can”).

The event also featured past winners of Rolex’s enterprise award, including a cave explorer, a leading authority on whale sharks and an entrepreneur who delivered cardiovascular care to rural communities in Cameroon. The watchmaker and the UCLA Anderson School of Management were both co-sponsors of the summit.

Favreau, who notably used stop animation for his holiday classic “Elf,” said he was especially proud of his work on this year’s live-action adaptation of “The Jungle Book.” He said the film succeeded in blurring the lines between special effects and reality by staying mostly true to physics and biology. Baloo in his adaptation, for example, looks like a real bear.

In one critical scene in which the protagonist leaves the pack of wolves that raised him, Favreau needed to capture an “on the verge of tears” level of emotion. So he gave his team the painstaking task of having the actor run his fingers through the fur of a make-believe wolf.

Conventional wisdom would have gone with the easier shot: hiding the actor’s hands on the other side of the animal to block the view of strands of fur coursing between his fingers. Instead, Favreau combined live actors with puppets to capture the interaction in the real world. Special effects workers then created a digital hand for Mowgli and filled in the animal’s movements.

“All of it, you didn’t know where the line was,” Favreau said of the scene.

Favreau has more recently turned his attention to virtual reality, which has the ability to make storytelling interactive.

In a separate panel, Spiteri, co-founder of the Venice-based VR studio Wevr, said the immersive technology was likely two to four years from becoming a mass-market tool.

The challenge now is getting as many people as possible to experience VR, which is why the start-up is partnering with massive technology companies such as Google and Facebook to reach an audience. Spiteri has been heartened by a movement in many cities where users can pay $10 to $15 to try a VR headset for half an hour — much like a modern-day video arcade.

“We’re ultimately trying to reach people,” Spiteri said.

In another area experiencing exponential growth, a panel of space experts spoke of investment and research in both satellites and launch systems making it easier to imagine the introduction of space tourism and Mars colonies.

“Things are a lot closer than you might think,” said Chad Anderson, managing director of Space Angels Network, an investment firm focused on commercial space ventures.

Will Pomerantz, vice president for special projects at Virgin Galactic, said his company wanted to make space travel far less exclusive, noting only 557 people — most of them roughly the same age — have had the privilege to venture into space.

“We want to make it so that if you’re healthy enough to ride a roller coaster, then you’re healthy enough to ride to space,” Pomerantz said.

On more earthly demands, Waters spoke about her efforts changing attitudes toward food in the United States, starting with schoolchildren.

The acclaimed chef, whose Berkeley restaurant Chez Panisse launched an American food revolution starting in the 1970s, walked out on stage with a quote by French gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin projected behind her: “The destiny of nations depends on how they nourish themselves.”

Only by educating children about the values of food can the country reverse its embrace of fast food and the health complications it carries, Waters said in a panel moderated by Times food critic Jonathan Gold. Waters is trying to expand her efforts to teach food as a curriculum at schools.

“I’ve come to understand it’s not just what we’re eating but the way we’re eating,” Waters said. “When we eat fast food, we digest the values that come with our food.”

Waters said the overwhelming majority of children don’t have one family meal a day.

“It’s stunning,” Gold said. “It’s the way families come together.”

“It’s the place where you say whether you did your homework or not,” Waters said.

Twitter: @dhpierson

ALSO

Chinese app maker comes to Santa Monica in a bid to build a live-streaming empire

Review: Ryan Phillippe tries to bring swagger to USA’s ‘Shooter,’ but it’s mostly a wishy-washy pose

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.