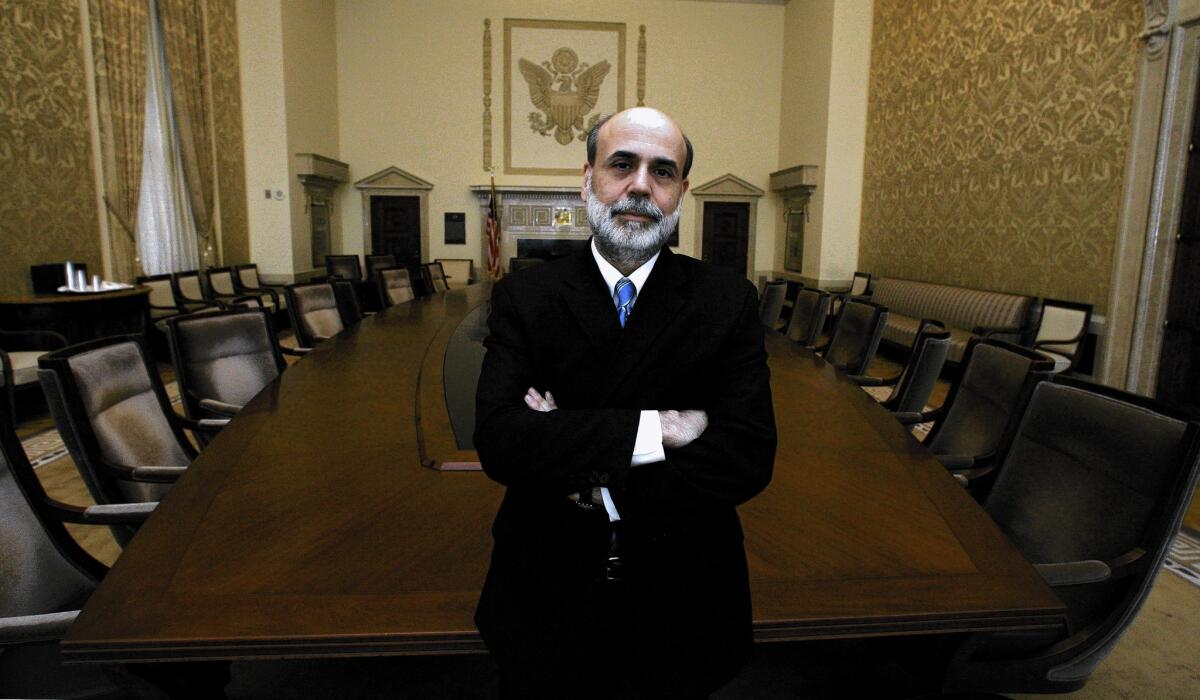

Bernanke leaves legacy of stimulus and stagnation

WASHINGTON — As Ben S. Bernanke walks away from the Federal Reserve’s marble headquarters on the Mall after presiding over his last policy meeting Wednesday, he will leave behind a bittersweet legacy.

On one hand, his unprecedented efforts to drive down interest rates and stimulate the economy are widely credited by his peers with saving the nation from a second Depression, strengthening the economic recovery and leaving the nation’s financial condition poised to take off this year.

Yet those same policies have added momentum to one of the greatest surges in economic inequality in U.S. history, helping the wealthiest Americans add to their enormous riches while the incomes of almost everyone else stagnated.

By driving interest rates down to historic lows, the Fed chairman helped fuel a huge surge in the stock market, where the wealthiest 1% of Americans have been far better positioned to take advantage of gains than their less affluent fellow citizens.

To be sure, his policies have helped those with 401(k) and retirement plans tied to the stock market. Also, low interest rates have stimulated housing sales and permitted many homeowners to save money by lowering their mortgage costs through refinancing.

But unemployment remains high by historical standards, and the financial strength of many workers has deteriorated. Most economists see little chance of that picture changing radically anytime soon.

Fed policy “did a wonderful job of keeping the financial system from falling off the table,” said Jack Ablin, chief investment officer with BMO Private Bank in Chicago. “But as a side effect or consequence, it’s driven a wedge between the haves and have-nots.”

Bernanke, whose term expires Friday, has repeatedly rebuffed the notion that his policies have done little for the masses.

“It’s simply not true,” he said publicly in November before rattling off ways that the Fed’s low-interest policies have benefited Main Street — cheaper car loans, recovering home values, stable consumer prices and more jobs.

Even so, from mid-2009, when the Great Recession ended, to 2011, the average net worth of the wealthiest 7% of households surged 28% to $3.2 million, according to Pew Research. For everybody else, such wealth — assets minus debts — fell 4% during that period to $133,817.

Since 2011, the disparity has grown. Stocks have jumped even higher in the last two years, according to data from Swiss financial services company Credit Suisse Group. And income statistics show a similar, though less dramatic, pattern.

Major corporations, meanwhile, have piled up millions of dollars in cash reserves.

The result is that inequality, which narrowed some during the recession as the stock market plummeted, has widened again and exacerbated a long-running problem that has surged to the forefront of public discourse for the rich and powerful gathered last week at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, as well as for U.S. policymakers and ordinary Americans.

President Obama is expected to press the matter in his State of the Union address Tuesday.

For Bernanke, it’s a subject that has evoked particular sensitivity as he has sought to dispel the public perception that the Fed was more interested in helping Wall Street than Main Street.

That image was etched on the minds of many people when the Fed engineered bailouts of such major financial firms as insurer American International Group Inc. and banking firm Citigroup Inc. along with General Motors Corp. and Chrysler during the 2007-09 recession.

In interviews with media, town-hall-style forums and visits to college campuses and even a military base, Bernanke has tried to explain to people why these controversial rescues and other funding programs were needed to revive credit markets and keep the economy from collapsing.

Bernanke’s groundbreaking efforts to engage the public and open up the Fed to the outside may be one of his lasting achievements as chairman; Vice Chairwoman Janet L. Yellen is expected to continue promoting that increased transparency as his successor.

Still, the Fed’s improved communications, effective with financial markets, have had limited success with ordinary folk.

One reason is the weak recovery, which has left many people disenchanted with politicians and policymakers in general.

Today, more than four years after attending Bernanke’s town hall meeting in Kansas City, Mo., Mary Rabon resents the working class being left out of the recovery. “I just don’t see that he’s done anything for the masses,” said the board chairwoman of Communities Creating Opportunity, a grass-roots organization.

Bernanke takes issue with such a view. “I don’t agree with that,” he said. “Jobs and low inflation — I can’t think of anything more mainstream than that.”

With interest rates low and credit access improving, car sales have rebounded sharply in the last 18 months, boosting auto production as well as investments and hiring at plants in the U.S. The Fed’s large-scale purchases of mortgage-backed securities have pushed down rates that have lifted home sales and values.

And unemployment has dropped significantly since the Fed’s latest round of bond-buying stimulus began in the fall of 2012, though much of that rate decline has come from an exodus of workers. Under Bernanke, the Fed has tied future shifts in stimulus and short-term interest rate policies directly to performance in the labor market, particularly jobless trends.

“I salute Bernanke and the rest of the Fed in understanding their obligations to try to reduce unemployment as best as they can,” said Robert B. Reich, a public policy professor at UC Berkeley. The Fed has a dual mandate from Congress to control inflation and maximize employment.

At the same time, the Clinton-era Labor secretary and many analysts wondered just how much monetary policy can bring down unemployment or help lift workers’ incomes, which are related to education and skills, new technologies and globalization — areas that lawmakers typically try to address with fiscal policy.

With so little coming out of Congress, “I’m glad Bernanke and Co. chose an expansionary monetary policy,” Reich said.

“On the other hand, I think history will show the Fed’s policy fueled widening inequality for the single reason that most average people didn’t have access to low-interest loans,” he said. “Wealthy people and corporations could borrow far more easily.”

Chris Rupkey, chief financial economist at the Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi in New York, agreed that the wealthiest 1% of Americans had reaped the lion’s share of stock market gains. But he sees signs that the public angst over economic inequality may already be influencing Fed policymaking.

He said Fed officials also were looking at workers’ wages and other labor indicators hinting at economic distribution issues.

“If employment comes down but wages aren’t going up, that feeds into the thinking that the economy is not in place.... It argues for the Fed keeping rates lower for longer,” Rupkey said. “For me, it’s not an appropriate variable for them to target. Central bankers shouldn’t be social workers.”

he economy is not in place.... It argues for the Fed keeping rates lower for longer,” Rupkey said. “For me, it’s not an appropriate variable for them to target. Central bankers shouldn’t be social workers.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.