Must Reads: Terry Semel’s Alzheimer’s battle: Inside the family war over the Hollywood titan’s care

Last May, Eric Semel, the eldest child and only son of former Warner Bros. chief Terry Semel, filed a petition in Los Angeles County Superior Court to appoint a temporary conservator for his father. Semel had been a lion of Hollywood during his heyday, winning admiration for the way he revolutionized the movie business during two decades at the top — and for the finesse with which he’d conducted himself while doing so. But by last year Semel, then 75 and suffering the ravages of Alzheimer’s, had for some time been unable to manage his personal or financial affairs.

Two years earlier, Semel’s wife, Jane, had put him in a nursing facility. Now Eric was claiming that his stepmother “was in serious breach of her fiduciary duties” and “causing serious harm to Terry’s health and safety, potentially rising to elder abuse and neglect.”

The allegations were as numerous as they were disturbing. In the filings, Jane is accused of instructing Semel’s private caregivers to change the dosages of his prescriptions or eliminate them altogether; ignoring repeated requests to take her husband, who also suffered from high blood pressure, for regular physical examinations; and refusing to allow him to leave the facility, curtailing his social activities. Semel, his son claimed, had been reduced to living in a 500-square-foot bedroom at the Motion Picture & Television Fund retirement community in Woodland Hills, against his expressed wish to remain at his home, a 13,000-square-foot Bel-Air mansion.

Jane Semel said in court filings that she moved her husband to the Motion Picture home on the advice of doctors. Before the warring factions reached a confidential agreement last fall, Jane disputed her stepson’s characterization of Semel as a “man dumped by his wife in a substandard facility and denied necessary medical care capriciously and against the advice of his doctors.” Her husband, she stated in a court filing, “is not the man he once was. He is sometimes confused and sometimes upset, but those are functions of his disease, not anything that anyone has done to him.” (Through his attorney, Eric Semel declined to comment.)

Eric Semel’s extraordinary campaign to revoke his stepmother’s authority over his father’s care set off a divisive family crisis while opening a window into Terry Semel’s well-being and treatment, which had been the subject of long-running speculation among friends and associates. How did one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in Hollywood — a man with considerable resources and influence, who had given millions to various philanthropic causes and owned homes in Los Angeles, New York City, the Hamptons and London — end up in a two-room unit in a home for the aged in the Valley?

The family’s probate fight also raised broader questions about the legal, financial and personal challenges of caring for someone with Alzheimer’s, a disease with no cure or treatment able to arrest its progression.

“The person that you designate as trustee can make decisions that can be completely contrary to your wishes,” said Martin Neumann, director at Weinstock Manion, a Los Angeles law firm specializing in trust and estates. If they do, “you’re out of luck,” said Neumann, who is not involved in the Semel case.

Semel married Jane, his second wife, in 1977. Together, they have three daughters. In her court filings, Jane noted that she had taken care of Semel for 41 years “with love and devotion” and made the case that she should continue to do so. Jane also asserted that she was authorized to exercise full control over her husband’s financial and personal affairs, including his healthcare. And she supplied proof: Semel had signed documents giving his wife power of attorney and making her his healthcare agent.

“The case to which you refer was settled to the satisfaction of all parties,” said Patricia Glaser, an attorney representing Jane Semel. “There was no finding of any breach of fiduciary duty by Jane. The ‘allegations’ against Jane were just that, mere allegations, and were abandoned. Jane has done and continues to do everything in her power to make Terry’s life the best that it can be with the help of highly trained professionals at every turn…. Terry is receiving wonderful care at the MPTF.”

Full statement from attorney Patricia Glaser »

From Queens to Hollywood

Semel grew up in Queens, New York. His father designed women’s coats, and his mother worked at a bus company. After an uninspired turn as an accountant, he joined a sales training program at Warner Bros. in 1965. Following a short detour to CBS and Disney, he returned to Warner and rose through the ranks, becoming president and chief operating officer in 1982. In 1994, Semel was named co-chairman alongside Bob Daly.

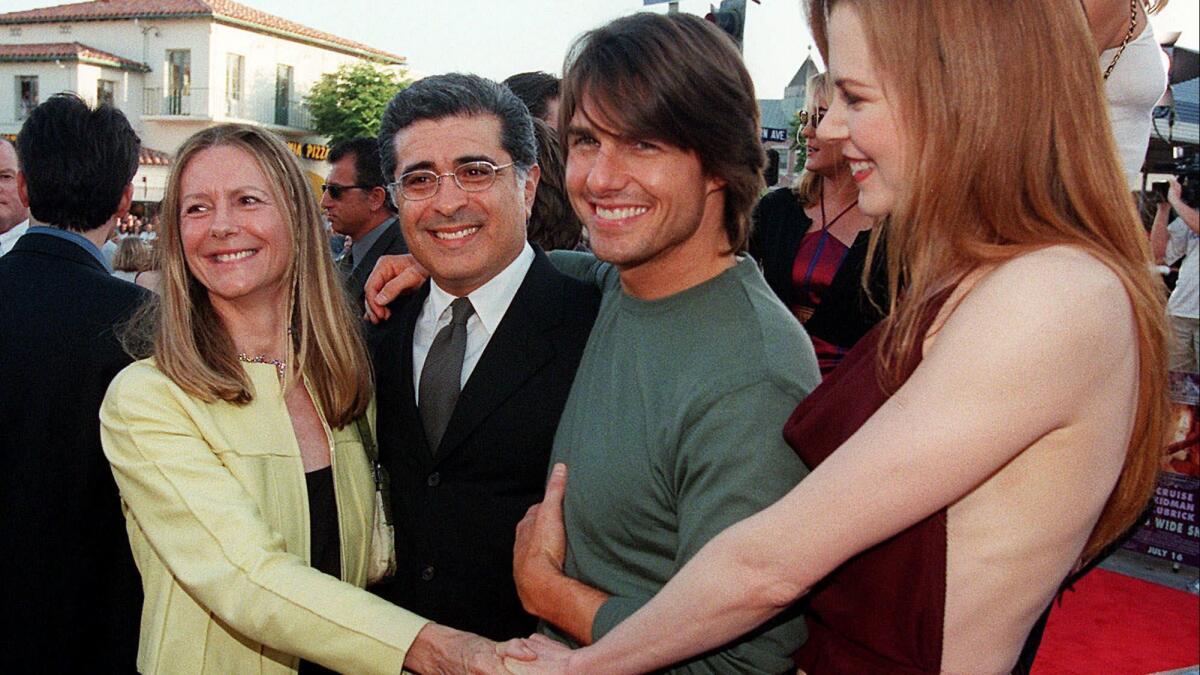

The Semel-Daly partnership was remarkably successful. They shared an assistant, lived on the same Bel-Air street and often rode to Warner’s Burbank offices together. Their nearly 20-year reign remains one of the most stable and profitable periods in Warner’s history; revenue ballooned from $1 billion to $11 billion. They racked up a number of blockbusters including “Batman,” television hits like “ER” and a string of Oscar winners, including “Driving Miss Daisy.”

During his time at Warner, Semel helped introduce novel ideas now considered industry standards, such as renting unused studio space to other filmmakers and making merchandising a core part of financing and marketing. He also helped transform Warner into a major player in television (in part by enlisting future CBS chief Leslie Moonves to lead the efforts).

Semel was known as daring, creative and elegant — a mentor to many. He was also a fierce deal maker. NBCUniversal Vice Chairman Ron Meyer, who has known Semel for decades, called him a “very smart, shrewd, tough negotiator. He knew his business as well as anybody.”

In 1999, as the studios’ corporate parents asserted more control, Semel and Daly announced their exit. The co-chairs had also weathered a string of flops.

“I knew if I didn’t go for another career now, I would probably get to the point in my life where I might not want to do something new at 60 or 61,” Semel told The Times, not long after leaving the studio with an estimated net worth of several hundred million dollars.

In 2001, Semel became chief executive of Yahoo, where his arrival was greeted with skepticism. After all, Semel barely used a computer. His assistant printed out his emails. In the cubicled, hoodied universe of Silicon Valley, Semel remained an anomaly. Reluctant to abandon his beloved Bel-Air estate, he kept on living there, even though Yahoo was based in the Bay Area; he flew up to San Francisco on his personal Gulfstream jet every Monday, staying at the Four Seasons hotel until Thursday. A chauffeur took him to Yahoo’s Sunnyvale offices.

At Warner, Semel burnished a reputation for canny deal making; at Yahoo, he became infamous for missed opportunities. After some initial success, Semel was criticized for, among other things, ceding Yahoo’s competitive position in search to Google and failing to buy both Google and Facebook.

The best deal he made at Yahoo may have been his own. By the time he stepped down in 2007, Semel had reportedly earned more than $430 million in compensation, according to Equilar, an executive compensation firm.

Back in Los Angeles in 2008, Semel resuscitated Windsor Media, the private investment firm he first launched after leaving Warner Bros. He devoted himself to philanthropic activities, sat on a number of boards and attended to a robust social life.

In a city not lacking significant art collections, the Semels possessed an impressive portfolio. Last year, Christie’s sold the Rothko they once owned for $31.1 million. In 2009, Semel was appointed co-chair of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s board of trustees.

But Semel’s circle of friends and business associates began noticing stark changes. Semel had always been erudite and impeccably turned out. Now he often appeared disheveled, forgetful and sometimes irritable at lunches and rounds of golf.

Diagnosis

In 2011, Semel, his wife and their daughter Lily traveled to Las Vegas to see Dr. Jeffrey Cummings, a neurologist affiliated with both UCLA and the Cleveland Clinic. There, according to Jane’s declaration in her petition to be appointed Semel’s conservator, Cummings reviewed Semel’s PET scan and delivered a diagnosis: Alzheimer’s.

Seven years earlier, Semel and his wife had donated $25 million to endow UCLA’s neuropsychiatric institute, which now bears their name. “We want to help lift the stigma that weighs heavily on millions of Americans suffering from diseases of the brain by inspiring greater public understanding of the impact of biology, genetics and culture on behavior and personal health,” Semel said at the time.

According to friends, the gift was more than an act of generosity. Semel’s mother, Mildred, had suffered from Alzheimer’s. She lived in a facility in Florida for more than 30 years until she died at 94. “He probably knew this was coming to some extent,” said one associate.

In the years after Semel’s diagnosis, several of his friends and colleagues said they observed his obvious decline but were not told that he had Alzheimer’s. According to Jane’s declaration, Semel asked to keep his diagnosis private, “so that he could remain engaged in his life as long as possible.”

“We still had lunch,” Meyer said. “He didn’t tell me, but I saw it coming. I saw him slowly deteriorate.”

Friends began hearing unsettling stories about his condition and care. “It was a very hush thing,” said a longtime associate. “Lots of people knew it and didn’t address it. He still went to things, and people would go, ‘Oof, that wasn’t good.’ He had no wherewithal; he was wandering around. Then I didn’t see him at anything anymore.”

For years, Richard Rosenblatt, CEO of TV Time, played a regular game of tennis with Semel. Then their meetings, emails and calls began to trail off. “He kind of dropped off the face of the Earth,” said Rosenblatt. “I thought he’d just gotten busy, and I didn’t want to push it.”

A few years ago, Rosenblatt ran into Semel at the Riviera Country Club. “He didn’t recognize me at all.”

Tech journalist Kara Swisher watched Semel’s decline up close. She first got to know him when she covered his tenure at Yahoo. The two became friendly, often dining and chatting about life and parenting.

Around 2013, when Swisher began raising money for Recode, the tech media website she co-founded, she met with Semel at the Windsor offices in Century City. “He seemed OK, slightly forgetful,” she recalled. “He was always a charming, absent-minded professor, but there were no big signs until after he invested.”

Semel injected $5 million into the venture. When Swisher tried to express her gratitude, she couldn’t reach him for a couple of weeks. The slowness of his response struck her as odd. So did his reaction when she finally got through to thank him for the money. He said, “‘What money?’” Swisher recalled. “I thought, ‘OK, rich person.’”

Arnon Milchan, founder of New Regency Pictures and a longtime friend, described a “heartbreaking” visit in 2016. Semel told Milchan about a new venture he was interested in, “and he was telling me the best guy to lead it was Arnon Milchan. The guy he was telling me about was me.”

As Semel declined, Jane largely oversaw decisions about his treatment and care.

Two individuals close to the family said there had been strains in the marriage for a number of years leading up to Semel’s diagnosis, but the couple remained married.

In his preliminary opposition to Jane’s petition to be appointed temporary conservator, Eric complained about Jane’s stewardship, asserting that his stepmother frequently traveled to London and New York, “leaving my father alone with his security guard at their Bel-Air home.” He also claimed in the same filing that his sister Lily told him that when Jane left town, she “dumped all of her responsibilities regarding Terry’s care onto [her].” (Lily Semel did not respond to a request for comment.)

Eric also reproached Jane for not making an effort to retrofit their Bel-Air home to accommodate his father. Instead, he claimed, she installed him in a small room at the house “unfit for his needs with concrete floors and without safety measures like guard rails.”

In June 2016, Semel fell at home and split open his head, according to the filings. “It became clear to me that the house was no longer safe for him,” Jane declared. Two months later, she had him moved to the retirement community operated by the Motion Picture & Television Fund.

Hollywood’s most famous nursing home

Approaching the high-security Motion Picture retirement community not far from Old Town Calabasas, drivers navigate a landscape of lush gardens resembling a manicured college campus. The nursing home opened in 1942 with support from the Motion Picture & Television Fund, established in 1921 by such luminaries as Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin to assist destitute actors and others in need. Today, the facilities are endowed by such entertainment stalwarts as Jodie Foster and Haim Saban, and include accommodations for independent and assisted living.

Jane’s petitions asserted that she kept her husband at home as long as she could, arranging for him to have regular visits with his doctors and bringing in private caregivers. But he had reached the point where it was “not in his best interest to live at his former home.” Semel, she argued, “was sometimes unable to control his physical impulses and occasionally frightened or endangered those around him.”

Jane said in the filings that her husband’s doctors recommended the move into the Motion Picture home, which has dedicated facilities for Alzheimer’s patients and could provide 24-hour care. She said she arranged for a two-bedroom suite in an assisted living villa and furnished it with familiar items that would make him comfortable.

But the move stunned family and friends.

“It broke the entire family apart,” said a close family friend, adding that Semel spent years building his expansive Bel-Air compound, occasionally expressing his desire to grow old and die there.

“I’m really upset about the situation,” said Victor Drai, a producer-turned-nightclub impresario who has known Semel for decades. “We were very good friends. I just loved Terry.”

Drai found it hard to imagine a plausible explanation for the move given Semel’s resources, wondering why he wasn’t housed in one of his other properties surrounded by 24-hour nurses, security, even a chef to see to his comfort and needs. “You put someone in a home when you have no money to take care of them,” Drai said. “He has all the money in the world.”

Another longtime friend and business associate visited him at the home and became concerned. Semel, seeming cognizant of his surroundings, told the friend that he didn’t think he’d survive there very long. “He didn’t like it,” this individual recalled. “He didn’t want to be with those people. He didn’t want to die there.”

Four other people close to Semel told The Times that Semel did not want to be in the Woodland Hills facility.

Experts say Alzheimer’s patients can become agitated in response to changes in scene. Although dedicated facilities can help Alzheimer’s patients, some families do care for their loved ones with the disease at home. President Reagan, for example, died at his Bel-Air estate in 2004.

During Semel’s time in the home, Eric contends that he became alarmed by reports from Semel’s private caregivers about his treatment. In sworn affidavits, one claimed that Jane gave the instruction to remove Semel’s daily Exelon patch, used to treat memory problems associated with Alzheimer’s. Another assertion was that she blocked his use of Seroquel at night, disrupting his sleep.

The affidavits, from two caregivers, also contained claims that Jane limited Semel’s food intake and that she did not immediately allow a doctor to give him antibiotics when he became sick with pneumonia and was taken to the UCLA emergency room. On multiple occasions, claimed one caregiver, “Mrs. Semel has asked me how long I think Terry will live.”

When Semel first went to the home in 2016, close friends said that he regularly left the facility to play tennis, golf, meet with friends for lunch and go to Denny’s, where he enjoyed breakfast. Then, according to one of his private caregiver’s affidavits, Jane instructed them “not to take Terry outside the nursing home anymore.”

Jane challenged many of these claims in her filings, saying that Semel’s doctors saw him regularly and that his medication dosages were being administered as directed. She also contended that Semel did not have pneumonia — but noted that antibiotics were prescribed when he went to the UCLA ER and that she personally picked them up.

Shortly after Eric filed his petition, a judge appointed attorney Andrew Wallet as temporary conservator. Wallet was until recently Britney Spears’ co-conservator along with her father. (Wallet declined to comment, citing confidentiality.)

Another attorney who was appointed by the court to represent Semel’s interests concluded that the ex-mogul lacked the capacity to give informed consent to any medical treatment.

That left Eric and Jane Semel to scrap about who should govern Semel’s care. Both sides enlisted a complement of lawyers. Eric questioned Jane’s legal authority, noting that his father signed over his power of attorney and made her his healthcare proxy (and Lily co-agent) when he “was suffering from dementia in the form of Alzheimer’s.” He called the circumstances of those designations “questionable.”

Another individual close to the Semel family said that some time after the former mogul’s diagnosis, a longtime friend of Semel’s was removed as a co-executor of his estate in the event of his death. However, the source said, this person was not informed at the time about the change or the reason for the removal.

As the case proceeded, Eric and Jane Semel committed in a tentative agreement to make “good faith efforts to determine” whether Terry Semel should remain in the Woodland Hills home or be moved to another location. The documents noted that Semel would continue to attend his doctor appointments and that results of medical tests would be shared with Eric. Further, they stated that neither Jane nor Lily could fire the private care staff who attended to Semel, including those who had filed affidavits with the court, without written agreement of both sides (Jane and Lily, and Eric) or by court order. At least one of Semel’s caregivers was terminated this year, according to a person familiar with the matter.

By September, the two sides reached a confidential agreement.

Terry Semel remains at the Motion Picture home. When he isn’t taking walks on the grounds, a family friend said, he sits in a La-Z-Boy chair in a room with a Picasso print on his wall. Alzheimer’s has rendered one of the richest and most powerful kingpins in Hollywood history helpless to achieve the end he’d wanted when he was well and as he grew sicker.

Meyer, who is on the MPTF Foundation’s board of governors, visited Semel some five months ago. “It’s a wonderful place,” he said. But he admitted he probably won’t be going back. “I’m ashamed. I love him. I’ve never known anybody with Alzheimer’s before, and it’s as if an alien has invaded my friend’s body. He doesn’t exist anymore.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.